PAGE NAVIGATION

- Introduction

- Context

- Key Actors

- Social Media Presence

- Offline Presence

- Impact of the Movement

- Critiques of Movement

- Conclusion

Introduction

The term Arab Spring came from the Revolution of 1848, which was a European democratic movement to remove old structures and create independent states,[1] and the Prague Spring in 1968, which produced strong reforms of political liberalization when Czechoslovakia was under the power of the Soviet Union. The term Arab Spring or Revolutions was used by news outlets, who predicted a democratic shift of the Arab countries.[2]

The Arab Spring, also known as the Arab Revolutions, began on December 17, 2010, and is considered to have been a revolutionary wave of both violent and nonviolent demonstrations, protests, riots, coups, and civil wars[3]. Today, the Arab Spring has resulted in rulers being ousted in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and Yemen. Additionally, public uprisings initiated in Bahrain and Syria; major protests in Algeria, Jordan, Kuwait, and Oman; and minor protests in Lebanon, Mauritania, Sudan, and Western Sahara. Social Media was an important part of this social movementbecause it was one tool among many that the Arab Spring utilized in order to spread information to a wide audience, but didn’t mobilize the people or cause the events in the Arab Spring.

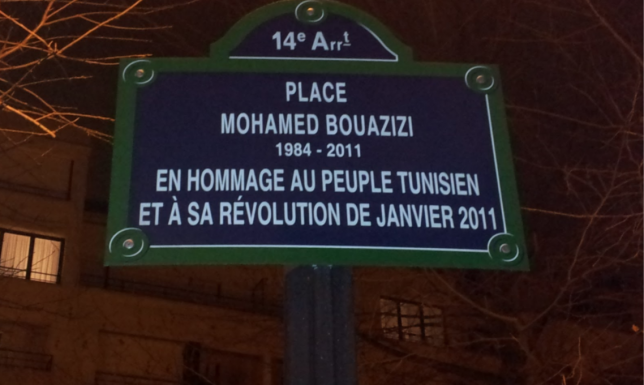

In 2010, 26-year-old Mohamed Bouazizi marched in front of a government building and set himself on fire. Moments before, Bouazizi was selling fruits and vegetables in the rural town of Sidi Bouzid in Tunisia when the police asked for his permit. He did not have a permit to sell goods, consequently, refusing to hand over his cart when the police attempted to take it. Police allegedly slapped him because of his refusal to hand over his unauthorized cart to the authorities. To file a complaint about this, he went to Governor’s office, but the governor refused to meet him. He screamed that if his claim were not redressed, he would torch himself. The humiliated vendor marched to the front of a government building and set himself on fire. His act of desperation in front of the government building resonated with what was at first hundreds and soon spread to countless countries. Protests began that day in Sidi Bouzid, captured by cellphone cameras and shared on the Internet. The momentum in Tunisia set off uprisings across the Middle East that became known as the Arab Spring. Mass protests grew all over Tunisia demanding justice for Bouazizi. After months of violent demonstrations, the revolutionaries took over the Presidential Lodge, and Zine El Abidine Ben Ali fled the country. Ultimately, the blazes from the body of Bouazizi “set the dictatorial regimens on fire.”[4]

Photo provided by Wikimedia Commons. Illustrates a protest in support of Mohamed Bouazizi, “Hero of Tunisia”.[5]

Context

History

The Arab Spring Movement was active in Middle Eastern and Northern African (MENA) countries from late 2010 until mid 2014. After the initial events in Tunisia, during which citizens were tired of repression, corrupt government officials, and a lack of economic opportunities, a crisis arose which spread from Tunisia to Egypt, Algeria, Bahrain, Yemen, Libya, and finally into Syria.[6] This political and social turbulence from trying to overthrow authoritarian governments also had an impact on other country’s regional views and geopolitical trends around the globe.[7]

Timeline

Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, the Tunisian president, was forced to flee after 23 years as the authoritarian leader there.[10]

Hosni Mubarak resigns from his position as the president of Egypt, leaving the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces his powers.[11]

Protests broke out in Benghazi against the dictator, which started an uprising that eventually turned into the Libyan Civil War.[12]

After the votes were counted, the two final candidates were Ahmed Shafik and Mohamed Morsi, Morsi ultimately won.[16]

Rebel forces captured and took control of Tripoli, Libya, overthrowing the government from dictator, Muammar Gaddafi.[13]

They protested against military rule and human rights violations after soldier’s abuse.[14]

Ali Abdullah Saleh resigned from his presidency and transferred his powers over to the Vice President, Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi.[15]

After over 225 people were killed in the massacre of the Tremseh Village, the International Committee of the Red Cross declared a civil war.[17]

In Benghazi, Libya, Islamic Militants killed U.S. Ambassador J. Christopher Stevens and Foreign Service Information Management Officer Sean Smith.[18]

Egyptian protests erupted from the dissatisfaction the of corrupt rule of Morsi, even though 80% of the population still supported his governance.[19]

Fighting ensues in northern Syria during this week between the Syrian opposition and the Islamic state of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL).[22]

After the Egyptian Government Resigned, defense minister Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi won the 2014 election with a 97% vote over the popular Hamdeen Sabahi.[23]

A major part of the war that lasted three years was the confrontation at the city of Homs by Syrian military forces and the Syrian opposition.[24]

December 2010

Suicide of Mohamed Bouazizi, a Tunisian street trader. Tired of the regime and not being able to escape it, he set himself on fire.[8] Egypt was in the midst of a war on terror that sparked the Arab Spring.[9]

January 2011

The Tunisian government was overthrown. Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, the Tunisian president, was forced to flee after 23 years as the authoritarian leader there.[10]

February 2011

The Egyptian President Resigns. Hosni Mubarak resigns from his position as the president of Egypt, leaving the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces his powers.[11]

February 2011

Backlash against Muammar Gaddafi’s regime in Libya. Protests broke out in Benghazi against the dictator, which started an uprising that eventually turned into the Libyan Civil War.[12]

August 2011

The Battle of Tripoli in Libya’s capital city. Rebel forces captured and took control of Tripoli, Libya, overthrowing the government from dictator, Muammar Gaddafi.[13]

December 2011

Women in Egypt protested. They protested against military rule and human rights violations after soldier’s abuse.[14]

February 2012

Resignation of the President of Yemen. Ali Abdullah Saleh resigned from his presidency and transferred his powers over to the Vice President, Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi.[15]

May 2012

First Egyptian Presidential election. After the votes were counted, the two final candidates were Ahmed Shafik and Mohamed Morsi, Morsi ultimately won.[16]

July 2012

Syrian Uprising officially declared a Civil War. After over 225 people were killed in the massacre of the Tremseh Village, the International Committee of the Red Cross declared a civil war.[17]

September 2012

Attack of the American Diplomatic Mission. In Benghazi, Libya, Islamic Militants killed U.S. Ambassador J. Christopher Stevens and Foreign Service Information Management Officer Sean Smith.[18]

November 2012

Protests began against the newly elected Egyptian President. Egyptian protests erupted from the dissatisfaction the of corrupt rule of Morsi, even though 80% of the population still supported his governance.[19]

March 2013

Syria becomes a member of the Arab League. Syrian forces captured Ar-Raqqah back from the rebel Al-Nisra Front, after it was one of the first cities taken from them in the Syrian Civil War.[20]

July 2013

Egyptian President deposed from his position. Mohamed Morsi was removed from his position after there was conflict between protesters and security guards.[21]

January 2014

Syrian Civil War Inter-Rebel Conflict. Fighting ensues in northern Syria during this week between the Syrian opposition and the Islamic state of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL).[22]

May 2014

Second Egyptian Presidential Election. After the Egyptian Government Resigned, defense minister Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi won the 2014 election with a 97% vote over the popular Hamdeen Sabahi.[23]

May 2014

Syrian Rebels withdraw from the siege of Homs. A major part of the war that lasted three years was the confrontation at the city of Homs by Syrian military forces and the Syrian opposition.[24]

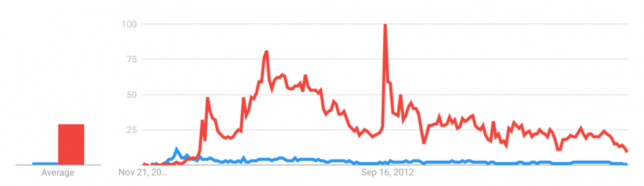

Google Trends Inflection Point Data – Arab Revolutions vs. Arab Spring

This graph from Google Trends, compares the searches of the two alternate movement names, “Arab Spring” and “Arab Revolution” throughout the movement from December 2010 through June 2014. In red, the search of “Arab Spring” is seen and the blue line represents the “Arab Revolution.”[25]

This graph from Google Trends, compares the searches of the two alternate movement names, “Arab Spring” and “Arab Revolution” throughout the movement from December 2010 through June 2014. In red, the search of “Arab Spring” is seen and the blue line represents the “Arab Revolution.”[25]

The term “Arab Revolution” appeared to have a popular inflection point first in February of 2011, while “Arab Spring” appeared in mid May of 2011. Arab Spring is searched more frequently, and is therefore a more popular name for the movement. It is apparent that the inflection points occur on days that major events happened.

There are three major spikes in the graph. The first spike corresponds with a failed assassination attempt on the president of Yemen, Ali Abdullah Saleh in early June of 2011.[26] The second spike occurs during a time when two major events happen in October of 2011. First, it correlates with when the Egyptian Army used tanks to attack protesters who were fighting against the destruction of a church. At the same time, the National Transitional Council (NTC) announced the end of the Libyan Civil War.[27] The third, and largest spike was following an international crisis for the United States after two U.S. officials were killed at the American Diplomatic Mission in Libya in September of 2012.

Political Spectrum Affiliation in Different Countries

Throughout the Arab Spring protests in North Africa and the Middle East, many different groups participated in the revolts against the authoritarian regimes in place. Some groups were calling for a westernized style of democracy, with freedom of speech, fair trials and equality as their calling. Others in this region argued that a religious democracy, based in Islam, should be the new governing style. In each country, a different dynamic took place. Although each nation followed a similar pattern, different groups working together to take down the current regime, while working against each other at the same time to obtain power in the new government.

Tunisia

In Tunisia, the protests erupted after a street vendor named Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire in protest of government corruption and lack of economic opportunity in Tunisia.[28] These people took to the streets in his hometown to protest the regime. After the regime cracked down on this protest and killed nearly 300 people,[29] mass protests began. Groups seeking non-religious and democracies and religious based groups like the Islamist Ennahda party joined together calling for President Ali’s removal.

Bahrain

In Bahrain, a small island ruled by monarchy just off the coast of Saudi Arabia, protesters have closer affiliations with religious groups. The majority of the country are Shia Muslims, and the ruling monarchy are Shiite Muslims,[30] leading to an uneasy rule. Similar to Tunisia, the non-violent protests were met with force by the government, leading to increased resistance from the people. The demands in Bahrain were for equal rights for the Shia population of Bahrain, and the ouster of the ruling monarchy.[31]

Egypt

In Egypt, the political affiliations stood out more than any other country involved in the Arab Spring besides Syria. Hosni Mubarak, the president and leader of the National Democratic party had been in power for over 30 years, with his son set to take over when Mubarak stepped down. Under Mubarak, Egypt had been cracking down on the Muslim Brotherhood for years, realizing the political power they could wield against him.[32] During the protests for Mubarak’s ouster, the Muslim Brotherhood protested alongside with pro-democracy activists. However, the Brotherhood eventually took over the protests and were elected into power after the resignation of Mubarak. The Muslim Brotherhood’s hold on power in Egypt was short lived, as a year after they came to power, millions of Egyptians went to the streets to protest and end their rule.

Yemen

In Yemen, multiple political groups, including tribal groups (small groups of ethnic minorities), were involved in the removal of President Ali Saleh.[33] Members of the current president’s own party resigned and Saleh eventually lost support from many leading members of his own tribal group.

Libya

In Libya, protesters from many different political groups came together for the ouster of Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi. The main group was the National Transition Council (NTC) which took control of the temporary government during the battle.[34] In order to reduce the Libyan government’s ability to beat the revolutionaries through an air campaign, a United Nations “no fly zone” was enforced over Libya, eliminating Gadhafi’s air control.[35] Again, many other groups, some with religious affiliations and others with secular goals in mind were a part of the conflict.

Syria

Perhaps the most notable conflict in the Arab Spring, the revolution to overthrow Bashar Al-Assad from power, is still going on today. While originally a crackdown on dissidents of Syrian nationalism, the Syrian conflict has grown today to one between Western & Eastern powers over who is the legit government. The Islamic State (ISIS) took advantage of this power vacuum and tried to establish a “caliphate,” or Islamic kingdom, across parts of Syria and Iraq. As Russia’s support of Assad grew stronger and fierce, the crackdowns on other groups involved only grew.

Key Actors

People

Tunisia

Mohamed Bouazizi was a street vendor in Sidi Bouzid, Tunisia who set himself on fire in front of a government building to protest government oppression and a lack of economic opportunities for Tunisians. After refusing to give up the cart of goods he was selling to police when they tried to confiscate it due to a lack of permit, police had a physical altercation with him. This resulted in Bouazizi taking the problem up the ranks to the governor. When the governor wouldn’t see him, he took action and set himself aflame. This sparked action in Tunisia that spread to other Middle Eastern and Northern African countries, known as the Arab Spring.[37]

President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali was the ruler of Tunisia who was removed during the Arab Spring.[38] Ben Ali came to power in 1987, leading a non-violent coup against former Tunisian leader Habib Bourguiba.[39] Early in his first term of office, Ben Ali began to introduce political and economic reforms that earned him support throughout the country. His reforms included terminating the lifetime position of the President, moving the country towards a liberal economy, and creating a social fund for the underprivileged.[40] In addition to these changes implemented, Ali and his government were also credited for halting the rise of non-secular Islamic political groups in Tunisia and promoting education while also supporting increased women’s rights.[41] While Ben Ali did bring positive change to Tunisia, he slowly began to increase his control over the country by heavily suppressing the freedom of the press and maintaining control over the military.[42] Although Ben Ali originally set a three term limit for the presidency, during his third term Ali was successful in changing Tunisia’s constitution to allow a fourth term. During this term Ben Ali moved to reinstall the no term limit presidency.[43] During Ben Ali’s third term of office, Tunisia began to suffer economically. These struggles continued through Al’s fourth term, the economy falling into extreme turmoil during his fifth term. Due to the lack of economic opportunities and mass unemployment amongst Tunisia’s young population, Tunisians took to the streets in December 2011 following street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi’s suicide in front of a government building.[44] After mass protests, the citizens of Tunisia successfully overthrew the Ben Ali regime. On January 14th, 2011 Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali stepped down from power and fled Tunisia for Saudi Arabia with his family.[45] The uprising in Tunisia was the first revolution in the Middle East and North Africa in 2011, beginning the Arab Spring.

Bahrain

King Hamad bin Isa al Khalifa of Bahrain was the focus of the Bahrain protests. Hamad became Emir of Bahrain following the death of his father in 1999.[46] Hamad also initially offered some political reforms, limiting the government’s powers of arresting and detaining people.[47] In 2002, Khalifa oversaw the creation of an elected parliament and a constitutional monarchy, making him King of Bahrain.[48] The parliament had little authority and power in Bahrain was solely in the hands of the King and the royal family.[49] In 2011 the youth of Bahrain peacefully protested the monarchy, demanding political reform.[50] King Hamad and the Bahrain security forces acted quickly, declaring a state of national emergency, forcefully cracking down on the protesters and jailing their leaders.[51] The Bahraini government was successful in quelling the protests and maintaining power. The protests in Bahrain did not garner as much attention as the revolutions across the Middle East due to the swift action of Bahrain’s rulers.[52]

Egypt

Wael Ghonim is a Google marketing executive based out of Egypt who created the page, “We are All Khaled Said.”[54] Ghonim created this page after learning of Khaled’s demise. Khaled had been beaten to death by Egyptian security forces during an interrogation.[55] Ghonim was responsible for some of the most famous social media posts during the revolution and began organizing revolutionaries for activism in Egypt. Ghonim himself was eventually captured by Egyptian security forces and later released. Today, he is a leading voice for social media activism and growing social media platforms for positive change.[56]

Hosni Mubarak who was president of Egypt for almost 30 years was the target of the revolution. Mubarak was Vice President of Egypt in 1981 when President Anwar Sadat was assassinated by Islamic militants.[57] Under Mubarak, Egypt has stayed in a state of national emergency throughout his entire rule, giving the government powers to arrest, severely limiting personal freedoms in the country.[58] Despite the limited freedoms, Egyptians tolerated Mubarak’s rule because he oversaw a period of peace in Egypt and the economy thrived.[59] The people of Egypt went to the streets on January 25th of 2011 to protest, following the uprising in Tunisia.[60] The government met the protesters with violent force, even shutting down the internet and mobile networks in the country in an effort to slow the organization of the protesters.[61] Less than a month after the protests began, Mubarak was removed from power and placed under arrest for his role in the violence against the protesters.[62]

Mohamed Morsi was the first elected president of Egypt after Mubarak’s departure. He was a member of the Muslim Brotherhood, an Islamic political party with ties to many Middle Eastern countries.[63] Despite the fact that he was democratically elected, many young Egyptians protested the non-secular aspect of a Morsi presidency and non-secular government. Within a year of being elected, protesters returned to the streets of Egypt to protest the Brotherhood’s rule in masses.[64] Seeing the massive protests by the people, the Egyptian military, led by General Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi removed Morsi from power and took control of Egypt.[65]

Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi was the winner of the second Egyptian presidential election in 2014. A powerful figure, General Sisi led the military coup against Mohamed Morsi.[66] Since his rise to power, Sisi has continued to keep Egypt in a military rule, enforcing strict rules under the guise of national security to secure his and the military’s control of the country.

Yemen

Ali Abdullah Saleh was the President of Yemen that protesters aimed to remove.[67] Saleh had ruled Yemen for over thirty years.[68] The protests began in January of 2011 and left between 200 and 2,000 protesters dead. The economic situation in Yemen was bleak, with little opportunity for the large population of Yemeni youth.[69] After months of protests and violent government opposition, President Saleh agreed to not hand power over to his son and sign an agreement giving power to the Vice President of Yemen.[70]

Libya

Muammar Gaddafi was the Libyan dictator who had ruled for 40 years. In the Libyan Arab Spring, the people of Libya turned against Gaddafi’s rule. Protesters demanded political change, tired of Gaddafi’s rule by force. When Gaddafi ordered the military to target civilian protesters to end the rebellion, outside nations got involved.[71] The United Nations declared a no fly zone over Libya to stop Gadhafi’s air force from fighting against the rebels, who had no air force. Multiple high ranking officers from the Libyan army began to break from the regime and join the rebels, eventually capturing and killing Gaddafi in his hometown of Sirte, Libya.[72] Following the death of Gaddafi, Libya fell into a failed state scenario with Islamic militant groups seizing control of much of the country.[73]

Syria

Bashar Al-Assad was the son of the former leader of Syria and current ruler. The Syrian Arab Spring revolts were aimed at removing Bashar Al-Assad. Assad inherited power in Syria, coming in to power following the death of his father.[74] Under the Assad families rule, Syrians enjoyed little to no political freedom and had no voice in government. The people of Syria saw the successes of other countries during the Arab Spring. He ordered his army to crush the revolt, which led Syria down a road of complete turmoil. Army units began to defy Assad, joining the Free Syrian army, the main group fighting against Assad’s forces.[75] Fighting today still continues in Syria as multiple groups, including ISIS control portions of the country. The Syrian Arab Spring went from a national event, to a geopolitical showdown with the USA and the West aligned with the rebels and Russia closely aligned with Assad to keep him in power.[76]

Demographics

The largest group of protesters in the Arab Spring movements were young men between the ages of 15-29.[77] For years, the population of young people in these countries grew exponentially, creating what political scientists deemed a “youth bulge.” [78] All of these young people are frustrated at the lack of citizen involvement in the government, and an extreme shortage of jobs and opportunities for the youth of these nations.[79] Another group that had a large presence in the Arab Spring were political groups that favored an Islamic nation. These groups included the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, which came to power after the Arab Spring removed Mubarak from power.[80] The political gains of many Islamist parties after the Arab Spring lead some to term the aftermath the “Islamist Winter.” [81] Although the Islamist groups were more organized behind the scenes of the protests, the largest group of activists and protesters came from the youth group.

Organizations

Throughout the Arab Spring, many civil-society organizations popped up in the various countries involved. Some were groups focused on civil structure and government after they deposed the current ruler, others had religious goals in mind. In addition to the civilian groups that formed there were each country’s own government agencies working to secure the current regime. As time went on, many from the current regimes defected to the opposition, refusing to continue the slaughter of civilian protesters. In addition to these smaller national organizations, there were also international groups involved in the Arab Spring uprising, some of these groups include:

Amnesty International

Amnesty International is a group dedicated to the protection of human rights. Amnesty International tracks the carnage in the countries affected by the Arab Spring and fights to report the truth about the many atrocities being committed during the turmoil. [82]

The Red Cross

The Red Cross association is dedicated to bringing medical supplies and treatment to the areas of conflict in the Arab World. Members of the Red Cross have even been the target for attacks in some of the countries they are helping in, making their mission an even harder task.[83]

United Nations (UN)

The United Nations, while trying to remain neutral in the conflict, eventually got involved. Increased violence by the Libyan government against the protesters eventually drew condemnation from the international community, leading the UN to get involved militarily. In Libya, the UN issued a no-fly zone, which limited Gaddafi’s air superiority over the rebel groups he was fighting. While the UN did not want to get involved in outside nations conflicts, the responsibility of protecting civilians led to a call to action.[84]

North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)

NATO was involved heavily in Libya, eventually taking command of the armed resistance against Gaddafi.[85] Acting under the authority of the UN directive, NATO support eventually led to Gaddafi’s ouster, as he could not defeat the rebels without his air force.

The White Helmets (Syria)

Source: WikiCommons

In Syria, a group known as the White Helmets have came to international prominence. This group is a volunteer organization, with no political affiliations that is dedicated to rescuing people after bombings in Syria. The White Helmets rush to sites of recent bombings and search to save civilians. To date, the White Helmets estimate they have saved almost 100,000 people in Syria. Sadly, over 200 members of the White Helmets have perished in Syria working to save others.[86]

Allies

No matter which side you were on during the Arab Spring, you had a multitude of allies to choose from. The current rulers of these countries called upon their long time allies to help ensure the safety of the regime, and the opposition relied on new allies, often old opponents of the regime to help their cause. This political situation was highlighted in the Syrian conflict more than anywhere else. Assad and the Syrian government had their backs against the wall and eventually called on ally Russia to help them survive. Under the context of operations against ISIS and other terrorist groups, Russia set up a military base in Syria and began conducting operations. Many of the operations were against opposition groups fighting Assad, not the Islamic terrorists they claimed to be fighting. The US and the West also took a stake in the Syrian conflict, arming various rebel factions. In Libya, Gaddafi relied on loyalist forces and eventually called in mercenaries (paid soldiers) from sub-Saharan African nations.[87] The National Transitional Council’s main ally, the UN/NATO proved to be a stronger ally and eventually helped the rebels overthrow Gadhafi and take Libya.[88]

Celebrity Endorsers

Celebrity endorsers of the #ArabSpring on social media were not as prominent as other social media revolutions. Instead, the people of the countries who broadcasted information through social media channels became the stars of the Arab Spring. There were many people who created content, informed international media on the situation on the ground, and also helped the civilians caught in the crossfire.

George Clooney

While not getting directly involved in a social media campaign regarding the Arab Spring, George Clooney, a famed Hollywood philanthropist and activist known for his campaign to stop the genocide in Darfur (South Sudan), signed on to executive produce a documentary about “The White Helmets.” As mentioned above the White Helmets are a volunteer organization dedicated to saving lives in the Syrian conflict. Although this documentary focused on the Syrian Civil war, it can be directly connected to the start of the uprising in the Arab Spring.[89]

Khalid Abdalla

Abdalla is a British born actor and activist who was present during the 2011 uprising in Tahrir Square in Cairo, Egypt. As seen in the movie “The Square,” he was standing alongside the many Egyptians who were tired of the regimes rule. In his fight for an alternative to Brotherhood or Military rule, he brought publicity to the protest and tried to enhance citizens’ civic engagement by sacrificing his time and being a voice for the country.[90]

Social Media Presence

Platforms Used

Many popular platforms have been used in spreading information and organizing protests during the Arab Spring. The platforms that people used in order to make their voices heard include Facebook,[91] Twitter, YouTube, blogs, and news outlets.[92] People spread current events with their friends using Facebook. Twitter hashtags gained the most momentum because of the site’s popularity. It was not uncommon to see posts written in arabic, but with English hashtags. Twitter was used to keep up to date on the Arab Spring by using short URLs or Bit.ly links to spread news outside of the region and many popular hashtags connected posts. YouTube is a popular video-sharing platform that was used to capture abuses by officials and protests against government officials. Facebook and Twitter were used to start revolutions.

People involved in the Arab Spring strongly believed in powerful internal platforms. They had created their own social media platforms that replaced some of the platforms described above. Aparat.com replaced YouTube and gained increasing popularity after 2011. Irexpert.ir, similar to LinkedIn, gained popularity among people in 2011 after the Arab Spring gained momentum. Finally, Cloob.com, used to replace Facebook, was consistently very popular throughout the duration of the Arab Spring as well as after it was over.[93] Even though these platforms weren’t exactly the same as the original platforms, they were popular in African countries and people still used them frequently, especially during the time of the Arab Spring.

Popular Hashtags

#ArabSpring

Emerging as the most documented hashtag used by all countries during the Arab Spring, #ArabSpring was used to unite countries together in the fight for fair governments. People from all over the world have used this hashtag on their social media posts in order to show their support for the uprisings.

This image shows a Tweet from a Twitter user, Noman Al-Husayn, who commonly posts on the Arab Spring uprisings. This also shows that the hashtags are all interconnected. [94]

#HumanRights

#HumanRights is another widely used hashtag since people were fighting for fair rights and representation within their country’s governments. This especially applies to women,since they are treated unequally in social as well as political settings and were trying to break these “norms” by using this hashtag online to raise awareness of their fight.

#Tunisia

#Tunisia is one of the more popular hashtags used throughout the movement to document the Arab Spring since protests first emerged from here.[96] The Tunisian government was also the first to be overthrown during this movement, which was a major highlight. It is seen on social media sites such as Facebook, Twitter, and even YouTube. It was highly used at the beginning of the Arab Spring, when the movement was first unfolding. In a Google Trends Search of #Tunisia during the time the Arab Spring was occurring showed a major spike at the beginning of the Arab Spring and a smaller spike of 40% around the end of February 2013. The inflection point at the beginning of the Arab Spring in January comes after the Tunisian government was overthrown and the President, Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, fled the country.[97] The second inflection point right after that shows up in the beginning of February after Egyptian protesters in Cairo, Egypt at Tahrir Square demanded the resignation of the president, Hosni Mubarak.[98] Lastly, in late February of 2013, U.N. Human Rights official, Navi Pillay, announces that the death toll of the Syrian Civil war is almost 700,000 people.[99] This must have sparked people’s interest to keep up to date on the war.

#Sidibouzid

Google Trends graph showing when #Sidibouzid emerged in 2010 and its use throughout the Arab Spring movement.[100]

Google Trends graph showing when #Sidibouzid emerged in 2010 and its use throughout the Arab Spring movement.[100]

The next most popular term searched was #Sidibouzid, which is the town where the protests of the Arab Spring first began. #Sidibouzid became a popular hashtag seen on Twitter in 2010 after the suicide of Tunisian street trader in the town of Sidi Bouzid, Tunisia.[101] According to the graph from Google Trends, there is one huge spike in searches followed by two smaller spikes after the beginning incident sparked a spread of the revolt to other countries. The first major spike is after the Tunisian government was overthrown and the second smaller spike followed the Egyptian protests in Tahrir Square, as explained above. The third inflection point occurred in May of 2011 was the confrontation at the city of Homs between Syrian military forces and the Syrian opposition.[102]

#Egypt

7.48 million tweets of #Egypt were seen from January 23, 2011 to November 30, 2011 with increased use during the Egyptian uprisings and revolutions. Most tweets using this hashtag were made by locals in their native Arabic language, discussing the political crisis that was occurring in their country. After president Mubarak’s resignation on February 11, 2011, there were 205,000 #Egypt retweets. It was used more by English speaking people during this time.[103]

#Jan25

January 25th was the first day of major day of revolt in Egypt. A major place of demonstration was Tahrir Square in Cairo, Egypt. The hashtag #Jan25 is a shortened version of the date that many protests around Egypt occurred and is used to separate these protests from ones in other countries.

#Libya

5.27 million tweets included the hashtag #Libya. It was mostly used by outsiders looking in and observing the revolt. The Libyan War ended with the capture of Colonel Gaddafi, and the hashtag’s use became less widespread.[104]

Meme vs. Cause

An opposition supporter wears bread on his head as a makeshift helmet during protests in Yemen February 3, 2011. REUTERS/Khaled Abdullah.[105]

My Hat is Bread

The “My Hat is Bread” meme was one of the social media creations that saw the most viral attention of the Arab Spring. During the Yemen protests, activists used makeshift helmets to protect themselves from projectiles.[106] Although meant to be comical in nature, this photo showed how civilians feared government crackdown while protesting. This picture spread rapidly throughout multiple news outlets the following day, including The Guardian, The Daily Mail, and Buzzfeed.[107] Throughout the Arab Spring, many different social media posts/memes were created, although no social media memes can actually be quantified into the effect it actually had.[108] The majority of online memes about the Arab Spring today are more closely aligned with the Syrian Civil War, which still rages on today. Mostly about Assad and his use of chemical weapons, the memes highlight the plight of the civilian people in Syria. The serious nature of the Arab Spring and the consequences for protesting against the government led to much of the social media content being graphic evidence of the atrocities committed by the regimes still in power. The cause of the Arab Spring was brought to attention through social media, unfortunately the memes created and social media content was not enough to spur direct involvement in many cases.

Important Social Media Posts/Pages of the Arab Spring

With the influx of citizen journalists posting content during the Arab Spring it would be almost impossible to single out the 10 “Most Important” posts of the revolution. Governments facing revolt also worked to shut down social media sites during the unrest, preventing the spread of information. However there are a few posts that garnered much attention and brought more people together against the regimes in power.

Facebook Page: We Are All Khaled Said

After uploading a video of Egyptian security forces pilfering drugs during a raid online, the security services came for Khaled Said. He was dragged out of a café and beaten to death. Security services claimed that Khaled had died after ingesting two bags full of drugs to avoid punishment, however images released showed Khaled had been severely beaten.[109] A Google marketing executive based in Egypt created the page to bring awareness to the government atrocities.

Twitter: Fawaz Rashed – “The Broadcast of the Revolution”

Egyptian political activist Fawaz Rashed, in detailing how social media was used by the revolutionaries and protesters, “We use Facebook to schedule protests, Twitter to coordinate, and YouTube to tell the world.”[110] This showed that social media was used in various ways to help the activists stay united. While social media was definitely a tool for the uprisings, observers of the Arab Spring are quick to point out it wasn’t the driving force of the uprising.[111]

YouTube: The Most Amazing Video on the Internet – #Egypt #Jan25 (Youtube)

Documenting the government’s crackdown on protesters, Tamer Shaaban, an Egyptian made a video combining clips from different news outlets that showed protesters covered in blood, with the government troops advancing. This video increased awareness throughout the world, especially the Arab world as to what was transpiring in Egypt.

Social Media Importance

The emerging younger generation used social media and the Internet to help spread information and user generated content more quickly throughout the Arab Spring Movement. It wasn’t used to actually cause the events that happened during the Arab Spring, but it was used as a tool to empower people to revolt against the authoritarian regimes. [112] Social media also was important in creating direct connections with people, allowing for greater visibility on what is going on as well as sharing ideas. Through online platforms, people could vote on matters as well as spread important documents.[113] Social media platforms were also essential in allowing women to participate, where otherwise they would not be seen as equal. Women online tried to break gender and social barriers between males and females. Women were influencing international revolutionary actions through social media accounts by challenging cultural and religious norms that had been going on for so long. By trying to achieve participatory democracy, people spread their ideas and initiate change in their society from the bottom up.[114] This “safe space” allowed for all to globally spread their concerns.

Organic vs. Planned Growth

The Arab Spring’s first revolution organically formed, occurring and spreading quickly due to social media. It was not until later, however, that a planned growth emerged and resulted because of the Arab Spring. The planned growth occurred in countless countries including Jordan, Libya, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, Algeria, and Egypt, each with significantly different economic and political results. The results being an increase in political stability while economic reforms remained unmoved.

Explicitly viewing each country, Jordan is a country whose attempt to economic reform did not succeed. Due to the Arab Spring, the country’s burden of its civil servants’ salaries and military spending was increased and as a result, increased subsidies as well. Concerns of fiscal deficits were raised as Jordan’s governor of the central bank was displaced. Still, there continues to be uncertainty of whether economic reform will take place. Similarly, Morocco reviewed their fiscal deficit, attempting to lower spending

by selling more state-held shares in their established companies. Both Jordan and Morocco have attempted to resolve deficits with investments and as a result, have impeded export growth.[115]

Offline Presence

Though social media played a key role in part of the Arab Spring because it spread information to a broad audience, it did not mobilize the people or cause the events in the Arab Spring. After the initial effects of the Tunisian Revolution, many nongovernmental organizations opened doors to leaders attempting to spread their voice beyond that of an online presence. This spreading of information included one-on-one interactions and strategy/resource sharing in the offices of the NGOs. This was done due to the amount of the population actually on social media platforms. Sources state that although 75% of the population used the Internet, only 24% used Facebook and 3% used Twitter. Additionally, in countries such as Egypt, 39% used the Internet, 10% used Facebook, and 1% used Twitter. The spreading of information from an offline presence, thus, became critical to bring awareness to much more large crowds. The organizational techniques used drove mobilization and spread news from the initial protests. Additionally, many of the NGO’s staff their staff affiliated themselves with informal organizations and identity groups, meaning that there were both global awareness and specific, targeted action. Much of the offline presence did not carry over to online presence and mobilization, however, did succeed in bringing a mass amount of individuals together to protest the government.

Photo is from Wikimedia Commons created by Faris Knight. Represents protests during the Arab Spring.[116]

Analog Antecedents

The Prague Spring

The so-called name of the “Arab Spring” roots back to The Cold War in 1968 which was a result of the World War ll. Specifically, during this time, the term “Prague Spring” derived from Czechoslovakia transient period of liberalization with frameworks such as freedom and political reforms was sought. Though the happenings of the Prague Spring still differentiated from that of the Arab Spring, both movements established prominent dates of change.[117]

Tunisian Revolution

Consequently, the Tunisian Revolution of 2011 marked the start of the Arab Spring. Also known as the “Jasmine Revolution,” this revolt arose from people’s civil resistance through street demonstrations. Within days of Mohamed’s act, uprisings rapidly expanded across the whole Tunisian country with protesters chanting slogans and demanding a solution to the vast unemployment and the critical economic state of the nation. Ben Ali, President of Tunisia at the time, officially resigned after 28 days on January 14, 2011, putting an end to his 23-year-long rule[118].

Impact of Movement

There is no doubt that the 2010 Arab Spring movement had a profound effect on the Middle East & North African countries that were involved. In Libya, Tunisia, and Egypt, longtime rulers were overthrown or killed. Unfortunately, many of the countries that overthrew the regime fell into more chaos, as power vacuums developed and many actors started fighting for that power. In Syria fighting still rages on today, with no side in complete control of the country and a civil war that has left almost a quarter-million people dead and millions displaced.[119] Social media’s role in change became clear. It could be utilized by the masses to organize a movement and also broadcast information unfiltered to the rest of the world. Some of the most critical ramifications on the region are:

The end of the “Untouchable” rulers

For years many of these dictators held a firm grip on power and limited civilian rights to challenge them. Brutality and force were often the main tool in enforcing their reign, but after the Arab Springs, rulers across the regions saw that they could no longer ignore the masses, and at the very least listen to their wishes and create some reforms.[120]

Political Activism

This movement has helped the Arab world realize through civil disobedience, changes can occur. Now, more than ever, young people in these countries are joining political groups and trying to help shape their country.[121]

Unrest and Civil War

For every good outcome of the Arab Spring, there has also been negative chain reactions. In the nations where the leader was ousted, various political groups seeking power immediately began the infighting. Islamist politicians wanted Sharia law and Islam to be made the official religion of the nation, secular activists argued for a system that resembled a western democracy, with freedom of speech, press and religion some of their main arguments. When one group took power in one of these nations, they quickly began ignoring the wishes of the other, leading to unrest and civil war in some countries[122]

Policy Achievements

Sadly for the Arab Spring protesters, there have been no real policy achievements or changes in many of the countries involved. Perhaps Tunisia is the only country involved in the Arab Spring that has actually changed the fabric of their government, creating a new constitution in 2014.[123] In countries like Bahrain, the regime stayed in place, promising reforms but not delivering on them, instead they cracked down on any government dissidents.[124] Libya, Syria, and Yemen are all failed states at this point and are in the middle of civil wars. If any policy achievement has came from the United States or Western world, it is simply wanting to avoid the mistakes of the past attempts at “Nation Building”.[125] Weary of the removal of Saddam Hussein in Iraq and Gaddafi in Libya, and what transpired after, the US was dedicated to staying out of the conflicts (on paper, CIA and other intelligence agencies are operating in these nations still).[126] In Egypt, Mohamed Morsi was democratically elected, yet a year into his term mass protests called for his ouster and the military overthrew and jailed Morsi. It is believed that today in Egypt there are less civil rights (challenging the government or military) than even before the revolution and Mubarak’s rule.[127]

Critiques of Movement

Concluding, the tragic event of Mohamed’s death became the start of an entire movement. Stating the series of events in order once more: Tunisian street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire on December 17, 2010. The President then, Ben Ali, fled Tunisia less than a month after. Egyptian cyber activists hashtagged their “day of rage” as #Jan25 which later included others such as #HumanRights and #ArabSpring. With that, it can be noted that most major tipping points occurred during winter. Critiques of the movement include that the metaphor has denoted a “time of renewal” where those who had opposed government control for decades before merely found themselves into the new season.[128]

Ultimately, the most common term “Arab Spring” has also been objected to it is stated to impose “blooming” from a “winter slumber.” Ultimately, this was not used by leaders of the movement and those organizing and participating throughout the revolutions. It has also become known that there is the even more offensive “Arab Awakening” suggests that the Arab populations were “asleep” throughout their brutally repressed by these regimes.

CONCLUSION

In summary, it can be noted that social media was an essential part of the Arab Spring because it was one tool among many that were utilized to spread information to a broad audience. It did not, however, mobilize the people or cause the events in the Arab Spring. The various countries that took part in the Arab Spring found results, whether politically or economically. Moreso, all found a voice and projected it throughout social media platforms. Mohamed Bouazizi’s act of desperation led to a movement that impacted lives around the world.

Team Member Bios:

Terilyn Rorke

I will graduate from the Haas School of Business at UC Berkeley in 2019. Moving to Berkeley from a small, quaint town has opened my eyes to the possibilities of creating big change after passionately studying social movements and participating in many meaningful protests.

Daisy Mendez

I am a student at UC Berkeley, Haas School of Business with a minor in Global Poverty and Practice. Within the minor program, I will apply my practice in the summer of 2018 and work with a nonprofit organization in the Middle East that supports human rights.

Lizet (Lisa) Ceja

Haas class of 2019. I have always been amazed at the effect social media can have and have enjoyed studying the various social movements. I look forward to continue studying social media as a medium for change and applying that in business to benefit society.

[1] R.J.W. Evans and Hartmut Pogge von Strandman, eds., The Revolutions in Europe 1848-1849. Volume, 4.

[2] Krauthammer, Charles. “The Arab Spring of 2005.” The Seattle Times, The Seattle Times Company, 21 March 2005, old.seattletimes.com/html/option/2002214060_krauthammer21.html

[3] Mahmood, Bilal. “Poverty and Revolution.” Poverty and Revolution, 30 Jan. 2015, articlesbybilal.blogspot.com/.

[4] Mahmood, Bilal. “Poverty and Revolution.” Poverty and Revolution, 30 Jan. 2015, articlesbybilal.blogspot.com/.

[5] Paris. A French protest in support of Mohamed Bouazizi, “Hero of Tunisia”. Antoine Walter. <p><a href=”https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:French_support_Bouazizi.jpg#/media/File:French_support_Bouazizi.jpg”><img src=”https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8f/French_support_Bouazizi.jpg/1200px-French_support_Bouazizi.jpg” alt=”French support Bouazizi.jpg”></a><br>By <a rel=”nofollow” class=”external text” href=”http://www.flickr.com/people/28222302@N06″>Antoine Walter</a> – <a href=”//commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Flickr” class=”mw-redirect” title=”Flickr”>Flickr</a>: <a rel=”nofollow” class=”external autonumber” href=”http://flickr.com/photos/28222302@N06/5361498172″>[1]</a>, <a href=”https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0″ title=”Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0″>CC BY-SA 2.0</a>, <a href=”https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=14794185″>Link</a></p>

[6] Fosshagen, Kjetil. Arab Spring : Uprisings, Powers, Interventions. New York : Berghahn, 2014., 2014. Critical interventions : a forum for social analysis: Volume 14. EBSCOhost,libproxy.berkeley.edu/login?qurl=http%3a%2f%2fsearch.ebscohost.com%2flogin.aspx%3fdirect%3dtrue%26db%3dcat04202a%26AN%3ducb.b21559746%26site%3deds-live.

[7] Arbatli, Ekim; Rosenberg, Dina (2007). Non-Western Social Movements and Participatory Democracy: Protest in the Age of Transnationalism. Springer International Publishing. pp. 161–170.

[8] Worth, Robert F. (21 January 2011). “How a Single Match Can Ignite a Revolution”. New York Times. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

[9] Fosshagen, Kjetil. Arab Spring : Uprisings, Powers, Interventions. New York : Berghahn, 2014., 2014. Critical interventions : a forum for social analysis: Volume 14. EBSCOhost, libproxy.berkeley.edu/login?qurl=http%3a%2f%2fsearch.ebscohost.com%2flogin.aspx%3fdirect%3dtrue%26db%3dcat04202a%26AN%3ducb.b21559746%26site%3deds-live.

[10] Fahim, Kareem (21 January 2011). “Slap to a Man’s Pride Set Off Tumult in Tunisia”. New York Times. p. 2. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

[11] “Hosni Mubarak resigns as president”. Al Jazeera. 11 February 2011.

[12] Cockburn, Patrick (24 June 2011). “Amnesty questions claim that Gaddafi ordered rape as weapon of war”. The Independent. London. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

[13] Kirkpatrick, David D.; Fahim, Kareem (23 August 2011). “Qaddafi’s Son Taunts Rebels in Tripoli”.The New York Times. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

[14] Kirkpatrick, David D. “Thousands of Women Mass in Major March in Cairo.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 20 Dec. 2011, www.nytimes.com/2011/12/21/world/middleeast/violence-enters-5th-day-as-egyptian-general-blames-protesters.html.

[15] Ghobari, Mohamed. “Yemeni President’s Term Extended, Shi’ite Muslim Leader Killed.” Reuters, Thomson Reuters, 21 Jan. 2014, www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-assassination/yemeni-presidents-term-extended-shiite-muslim-leader-killed-idUSBREA0K13420140121.

[16] “Muslim Brotherhood-Backed Candidate Morsi Wins Egyptian Presidential Election.” Fox News, FOX News Network, 24 June 2012, www.foxnews.com/world/2012/06/24/egypt-braces-for-announcement-president.html.

[17] “Syria in Civil War, Red Cross Says.” BBC News, BBC, 15 July 2012, www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-18849362.

[18] Review of the Terrorist Attacks on U.S. Facilities in Benghazi, Libya, September 11-12, 2012. United States Senate, 2014, pp. 1–16.

[19] McCrumen, Stephanie; Hauslohner, Abigail (5 December 2012). “Egyptians take anti-Morsi protests to presidential palace”. The Independent. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

[20] Jazeera, Al. “Syria Rebels Capture Northern Raqqa City.” Al Jazeera, Al Jazeera, 4 Mar. 2013, www.aljazeera.com/news/middleeast/2013/03/201334151942410812.html.

[21] Sayah, Ben Wedeman. Reza, and Matt Smith. “Coup Topples Egypt’s Morsy; Deposed President under ‘House Arrest’.” CNN, Cable News Network, 4 July 2013, edition.cnn.com/2013/07/03/world/meast/egypt-protests/index.html?hpt=hp_t1.

[22] Chulov, Martin. “Syrian Opposition Turns on Al-Qaida-Affiliated Isis Jihadists near Aleppo.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 3 Jan. 2014, www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jan/03/syrian-opposition-attack-alqaida-affiliate-isis.

[23] Al-Awsat, Asharq. “Sisi, Sabahi to Face off for Egyptian Presidency.” ASHARQ AL-AWSAT English Archive, Asharq Al Awsat – Sub Division of SRPC, 21 Apr. 2014, eng-archive.aawsat.com/theaawsat/news-middle-east/sisi-sabahi-to-face-off-for-egyptian-presidency.

[24] Aboud, Assaf. “Syria Conflict: Rebels Evacuated from Old City of Homs.” BBC News, BBC, 7 May 2014, www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-27306525

[25] “Google Trends.” Comparison of Arab Spring to Arab Revolution from November 2010 to June 2014. 18 Nov. 2017. https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=2010-11-30%202014-06-30&q=Arab%20Spring,Arab%20Revolution

<script type=”text/javascript” src=”https://ssl.gstatic.com/trends_nrtr/1225_RC02/embed_loader.js”></script> <script type=”text/javascript”> trends.embed.renderExploreWidget(“TIMESERIES”, {“comparisonItem”:[{“keyword”:”Arab Spring”,”geo”:””,”time”:”2010-11-30 2014-06-30″},{“keyword”:”Arab Revolution”,”geo”:””,”time”:”2010-11-30 2014-06-30″}],”category”:0,”property”:””}, {“exploreQuery”:”date=2010-11-30 2014-06-30,2010-11-30 2014-06-30&q=Arab%20Spring,Arab%20Revolution”,”guestPath”:”https://trends.google.com:443/trends/embed/”}); </script>

[26] Jazeera, Al. “Wounded Yemeni President in Saudi Arabia.” Al Jazeera, Al Jazeera, 5 June 2011, www.aljazeera.com/news/middleeast/2011/06/201164164346765100.html.

[27] Jazeera, Al. “NTC Declares ‘Liberation of Libya’.” Al Jazeera, Al Jazeera, 24 Oct. 2011, www.aljazeera.com/news/africa/2011/10/201110235316778897.html.

[28] “Arab Uprising: Country by Country – Tunisia.” BBC News, BBC, 16 Dec. 2013, www.bbc.com/news/world-12482315.

[29] “Arab Uprising: Country by Country – Tunisia.” BBC News, BBC, 16 Dec. 2013, www.bbc.com/news/world-12482315.

[30] “Arab Spring: A Research & Study Guide * الربيع العربي: Bahrain.” LibGuides, 27 June 2017, guides.library.cornell.edu/c.php?g=31688&p=200754.

[31] “Arab Spring: A Research & Study Guide * الربيع العربي: Bahrain.” LibGuides, 27 June 2017, guides.library.cornell.edu/c.php?g=31688&p=200754.

[32] “Arab Spring: A Research & Study Guide * الربيع العربي: Egypt.” LibGuides, guides.library.cornell.edu/c.php?g=31688&p=200748.

[33] “Arab Spring: A Research & Study Guide * الربيع العربي: Yemen.” LibGuides, guides.library.cornell.edu/c.php?g=31688&p=200752.

[34] “Arab Uprising: Country by Country – Libya.” BBC News, BBC, 16 Dec. 2013, www.bbc.com/news/world-12482311.

[35] “Arab Uprising: Country by Country – Libya.” BBC News, BBC, 16 Dec. 2013, www.bbc.com/news/world-12482311.

[36] Ordifana75. “Paris 14e Arrondissement – Place Mohamed-Bouazizi – Plaque De Rue.” Commons.wikimedia.org/Wiki/Category:Images, 10 Jan. 2012, upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/ff/Paris_14e_-_Place_Mohamed-Bouazizi_-_plaque.jpg.

Embed Code: <p><a href=”https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Paris_14e_-_Place_Mohamed-Bouazizi_-_plaque.jpg#/media/File:Paris_14e_-_Place_Mohamed-Bouazizi_-_plaque.jpg”><img src=”https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/ff/Paris_14e_-_Place_Mohamed-Bouazizi_-_plaque.jpg/1200px-Paris_14e_-_Place_Mohamed-Bouazizi_-_plaque.jpg” alt=”Paris 14e – Place Mohamed-Bouazizi – plaque.jpg”></a><br>By <a href=”//commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:Ordifana75″ title=”User:Ordifana75″>Ordifana75</a> – <span class=”int-own-work” lang=”en”>Own work</span>, <a href=”https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0″ title=”Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0″>CC BY-SA 3.0</a>, <a href=”https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18015181″>Link</a></p>

[37] “Arab Spring: A Research & Study Guide * الربيع العربي: Tunisia.” LibGuides, guides.library.cornell.edu/c.php?g=31688&p=200750.

[38] “Arab Spring: A Research & Study Guide * الربيع العربي: Tunisia.” LibGuides, guides.library.cornell.edu/c.php?g=31688&p=200750.

[39] Jazeera, Al. “Profile: Zine El Abidine Ben Ali.” News | Al Jazeera, Al Jazeera, 14 Jan. 2011, www.aljazeera.com/indepth/spotlight/tunisia/2011/01/201111502648916419.html.

[40] Jazeera, Al. “Profile: Zine El Abidine Ben Ali.” News | Al Jazeera, Al Jazeera, 14 Jan. 2011, www.aljazeera.com/indepth/spotlight/tunisia/2011/01/201111502648916419.html.

[41] Jazeera, Al. “Profile: Zine El Abidine Ben Ali.” News | Al Jazeera, Al Jazeera, 14 Jan. 2011, www.aljazeera.com/indepth/spotlight/tunisia/2011/01/201111502648916419.html.

[42] Jazeera, Al. “Profile: Zine El Abidine Ben Ali.” News | Al Jazeera, Al Jazeera, 14 Jan. 2011, www.aljazeera.com/indepth/spotlight/tunisia/2011/01/201111502648916419.html.

[43] Jazeera, Al. “Profile: Zine El Abidine Ben Ali.” News | Al Jazeera, Al Jazeera, 14 Jan. 2011, www.aljazeera.com/indepth/spotlight/tunisia/2011/01/201111502648916419.html.

[44] Jazeera, Al. “Profile: Zine El Abidine Ben Ali.” News | Al Jazeera, Al Jazeera, 14 Jan. 2011, www.aljazeera.com/indepth/spotlight/tunisia/2011/01/201111502648916419.html.

[45] “Arab Spring: A Research & Study Guide * الربيع العربي: Tunisia.” LibGuides, 27 June 2017, guides.library.cornell.edu/c.php?g=31688&p=200750.

[46] The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. “Sheikh Ḥamad Ibn ʿIsā Āl Khalīfah.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 15 Mar. 2016, www.britannica.com/biography/Sheikh-Hamad-ibn-Isa-Al-Khalifah.

[47] The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. “Sheikh Ḥamad Ibn ʿIsā Āl Khalīfah.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 15 Mar. 2016, www.britannica.com/biography/Sheikh-Hamad-ibn-Isa-Al-Khalifah.

[48] The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. “Sheikh Ḥamad Ibn ʿIsā Āl Khalīfah.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 15 Mar. 2016, www.britannica.com/biography/Sheikh-Hamad-ibn-Isa-Al-Khalifah.

[49] The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. “Sheikh Ḥamad Ibn ʿIsā Āl Khalīfah.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 15 Mar. 2016, www.britannica.com/biography/Sheikh-Hamad-ibn-Isa-Al-Khalifah.

[50] The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. “Sheikh Ḥamad Ibn ʿIsā Āl Khalīfah.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 15 Mar. 2016, www.britannica.com/biography/Sheikh-Hamad-ibn-Isa-Al-Khalifah.

[51] The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. “Sheikh Ḥamad Ibn ʿIsā Āl Khalīfah.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 15 Mar. 2016, www.britannica.com/biography/Sheikh-Hamad-ibn-Isa-Al-Khalifah.

[52] “Arab Spring: A Research & Study Guide * الربيع العربي: Bahrain.” LibGuides, guides.library.cornell.edu/c.php?g=31688&p=200754.

[53] Studio Photo. “Category:Wael Ghonim.” Category:Wael Ghonim – Wikimedia Commons, 14 Feb. 2011, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Wael_Ghonim#/media/File:Wael_ghonim.jpg. Embed Code:

<p><a href=”https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wael_ghonim.jpg#/media/File:Wael_ghonim.jpg”><img src=”https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/81/Wael_ghonim.jpg” alt=”Wael ghonim.jpg”></a><br>By Studio photo – Wael Ghonim through Email, <a href=”https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0″ title=”Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0″>CC BY-SA 3.0</a>, <a href=”https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=13302891“>Link</a></p>

[54] “Programmes – Egypt: ‘We Are All Khaled Said.’” BBC World Service, BBC, www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/programmes/2011/02/110217_outlook_egypt_protests_khaled_said.shtml.

[55] “Programmes – Egypt: ‘We Are All Khaled Said.’” BBC World Service, BBC, www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/programmes/2011/02/110217_outlook_egypt_protests_khaled_said.shtml.

[56] “Programmes – Egypt: ‘We Are All Khaled Said.’” BBC World Service, BBC, www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/programmes/2011/02/110217_outlook_egypt_protests_khaled_said.shtml.

[57] “Profile: Hosni Mubarak.” BBC News, BBC, 24 Mar. 2017, www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-12301713.

[58] “Profile: Hosni Mubarak.” BBC News, BBC, 24 Mar. 2017, www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-12301713.

[59] “Profile: Hosni Mubarak.” BBC News, BBC, 24 Mar. 2017, www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-12301713.

[60] “Arab Spring: A Research & Study Guide * الربيع العربي: Egypt.” LibGuides, guides.library.cornell.edu/c.php?g=31688&p=200748.

[61] “Arab Spring: A Research & Study Guide * الربيع العربي: Egypt.” LibGuides, guides.library.cornell.edu/c.php?g=31688&p=200748.

[62] “Arab Spring: A Research & Study Guide * الربيع العربي: Egypt.” LibGuides, guides.library.cornell.edu/c.php?g=31688&p=200748.

[63] “Arab Spring: A Research & Study Guide * الربيع العربي: Egypt.” LibGuides, guides.library.cornell.edu/c.php?g=31688&p=200748.

[64] “Arab Spring: A Research & Study Guide * الربيع العربي: Egypt.” LibGuides, guides.library.cornell.edu/c.php?g=31688&p=200748.

[65] “Arab Spring: A Research & Study Guide * الربيع العربي: Egypt.” LibGuides, guides.library.cornell.edu/c.php?g=31688&p=200748.

[66] Preston, Jennifer. “Movement Began With Outrage and a Facebook Page That Gave It an Outlet.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 5 Feb. 2011, www.nytimes.com/2011/02/06/world/middleeast/06face.html.

[67] “Arab Uprising: Country by Country – Yemen.” BBC News, BBC, 16 Dec. 2013, www.bbc.com/news/world-12482293.

[68] “Arab Uprising: Country by Country – Yemen.” BBC News, BBC, 16 Dec. 2013, www.bbc.com/news/world-12482293.

[69] “Arab Uprising: Country by Country – Yemen.” BBC News, BBC, 16 Dec. 2013, www.bbc.com/news/world-12482293.

[70] “Arab Uprising: Country by Country – Yemen.” BBC News, BBC, 16 Dec. 2013, www.bbc.com/news/world-12482293.

[71] “Arab Spring: A Research & Study Guide * الربيع العربي: Libya.” LibGuides, guides.library.cornell.edu/c.php?g=31688&p=200751.

[72] “Arab Spring: A Research & Study Guide * الربيع العربي: Libya.” LibGuides, guides.library.cornell.edu/c.php?g=31688&p=200751.

[73] “Arab Spring: A Research & Study Guide * الربيع العربي: Libya.” LibGuides, guides.library.cornell.edu/c.php?g=31688&p=200751.

[74] “Arab Spring: A Research & Study Guide * الربيع العربي: Syria.” LibGuides, guides.library.cornell.edu/c.php?g=31688&p=200753.

[75] “Arab Spring: A Research & Study Guide * الربيع العربي: Syria.” LibGuides, guides.library.cornell.edu/c.php?g=31688&p=200753.

[76] “Arab Spring: A Research & Study Guide * الربيع العربي: Syria.” LibGuides, guides.library.cornell.edu/c.php?g=31688&p=200753.

[77] “Demographics of Arab Protests.” Council on Foreign Relations, Council on Foreign Relations, www.cfr.org/interview/demographics-arab-protests.

[78] “Demographics of Arab Protests.” Council on Foreign Relations, Council on Foreign Relations, www.cfr.org/interview/demographics-arab-protests.

[79] “Demographics of Arab Protests.” Council on Foreign Relations, Council on Foreign Relations, www.cfr.org/interview/demographics-arab-protests.

[80] Hamid, Shadi. “Islamism, the Arab Spring, and the Failure of America’s Do-Nothing Policy in the Middle East.” Brookings, Brookings, 8 Aug. 2016, www.brookings.edu/blog/markaz/2015/10/14/islamism-the-arab-spring-and-the-failure-of-americas-do-nothing-policy-in-the-middle-east/.

[81] Hamid, Shadi. “Islamism, the Arab Spring, and the Failure of America’s Do-Nothing Policy in the Middle East.” Brookings, Brookings, 8 Aug. 2016, www.brookings.edu/blog/markaz/2015/10/14/islamism-the-arab-spring-and-the-failure-of-americas-do-nothing-policy-in-the-middle-east/.

[82] “Who We Are.” Home, www.amnesty.org/en/who-we-are/.

[83] “Arab Spring Creating Major Humanitarian Challenges across Middle East – Red Cross.” Arabian Gazette, 28 June 2012, arabiangazette.com/red-cross-warns-arab-spring-challenges/.

[84] Grant, Mark L. “The UN’s Response to the Arab Spring and the Evolving Role of the Security Council.” Arab Spring. www.una.org.uk/sites/default/files/Address%20to%20the%20UN%20APPG%20by%20Sir%20Mark%20Lyall%20Grant,%202%20May%202012.pdf.

[85] Rasmussen, Anders Fogh. “NATO and the Arab Spring.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 1 June 2011, www.nytimes.com/2011/06/01/opinion/01iht-edrasmussen01.html.

[86] Campaign, The Syria. “Meet the Heroes Saving Syria.” Support the White Helmets, www.whitehelmets.org/en.

[87] The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. “Libya Revolt of 2011.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 20 Apr. 2016, www.britannica.com/event/Libya-Revolt-of-2011.

[88] The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. “Libya Revolt of 2011.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 20 Apr. 2016, www.britannica.com/event/Libya-Revolt-of-2011.

[89] McNary, Dave. “George Clooney to Develop Movie on ‘White Helmets’ Rescuers in Syria.” Variety, 20 Dec. 2016, variety.com/2016/film/news/george-clooney-white-helmets-rescuers-syria-1201945608/.

[90] “THE SQUARE“. Kaleidoscope Entertainment. British Board of Film Classification. December 20, 2013. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

[91] Adi, Mohammad-Munir. The Usage of Social Media in the Arab Spring : The Potential of Media to Change Political Landscapes throughout the Middle East and Africa. Berlin : Lit, [2014], 2014. Internet economics = Internetökonomie: v./Bd. 8. EBSCOhost, libproxy.berkeley.edu/login?qurl=http%3a%2f%2fsearch.ebscohost.com%2flogin.aspx%3fdirect%3dtrue%26db%3dcat04202a%26AN%3ducb.b21643328%26site%3deds-live.

[92] Jamali, Reza. Online Arab Spring: Social Media and Fundamental Change. Chandos, 2015.

[93] Jamali, Reza. Online Arab Spring: Social Media and Fundamental Change. Chandos, 2015.

[94] Al-Husayn, Noman. “Noman Al-Husayn (@noman_husayn).” Twitter, Twitter, 27 Aug. 2017, https://twitter.com/noman_husayn.

Embed Code: <blockquote class=”twitter-tweet” data-lang=”en”><p lang=”en” dir=”ltr”><a href=”https://twitter.com/hashtag/Egypt?src=hash&ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw”>#Egypt</a> <a href=”https://twitter.com/hashtag/arabspring?src=hash&ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw”>#arabspring</a> <a href=”https://twitter.com/hashtag/economics?src=hash&ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw”>#economics</a> <a href=”https://twitter.com/hashtag/progress?src=hash&ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw”>#progress</a> When inflation exceeds a populations ability to maintain then democratic reform is required</p>— Noman Al-Husayn (@noman_husayn) <a href=”https://twitter.com/noman_husayn/status/901755542799921152?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw”>August 27, 2017</a></blockquote> <script async src=”https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js” charset=”utf-8″></script>

[95] “Google Trends.” #Tunisia from November 2010 to June 2014. 18 Nov. 2017.

[96] Adi, Mohammad-Munir. The Usage of Social Media in the Arab Spring : The Potential of Media to Change Political Landscapes throughout the Middle East and Africa. Berlin : Lit, [2014], 2014. Internet economics = Internetökonomie: v./Bd. 8. EBSCOhost, libproxy.berkeley.edu/login?qurl=http%3a%2f%2fsearch.ebscohost.com%2flogin.aspx%3fdirect%3dtrue%26db%3dcat04202a%26AN%3ducb.b21643328%26site%3deds-live.

[97] Fahim, Kareem (21 January 2011). “Slap to a Man’s Pride Set Off Tumult in Tunisia”. New York Times. p. 2. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

[98] Shenker, Jack. “Cairo’s Biggest Protest Yet Demands Mubarak’s Immediate Departure.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 5 Feb. 2011, www.theguardian.com/world/2011/feb/05/egypt-protest-demands-mubarak-departure.

[99] Fantz, Ashley. “Syria Death Toll Probably at 70,000, U.N. Human Rights Official Says.” CNN, Cable News Network, 12 Feb. 2013, edition.cnn.com/2013/02/12/world/meast/syria-death-toll/index.html?hpt=hp_t1.

[100] “Google Trends.” #Sidibouzid from November 2010 to June 2014. 18 Nov. 2017.

https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=2010-11-30%202014-06-30&q=%23Sidibouzid

<script type=”text/javascript” src=”https://ssl.gstatic.com/trends_nrtr/1173_RC01/embed_loader.js”></script> <script type=”text/javascript”> trends.embed.renderExploreWidget(“TIMESERIES”, {“comparisonItem”:[{“keyword”:”#sidibouzid”,”geo”:””,”time”:”2010-11-30 2014-06-30″}],”category”:0,”property”:””}, {“exploreQuery”:”date=2010-11-30 2014-06-30&q=%23sidibouzid”,”guestPath”:”https://trends.google.com:443/trends/embed/”}); </script>

[101] Worth, Robert F. (21 January 2011). “How a Single Match Can Ignite a Revolution”. New York Times. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

[102] Aboud, Assaf. “Syria Conflict: Rebels Evacuated from Old City of Homs.” BBC News, BBC, 7 May 2014, www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-27306525.

[103] Bruns, Axel, Tim Highfield, and Jean Burgess. “The Arab Spring and Social Media Audiences: English and Arabic Twitter Users and Their Networks.” American Behavioral Scientist 57, no. 7 (July 1, 2013): 871–98.

[104] Bruns, Axel, Tim Highfield, and Jean Burgess. “The Arab Spring and Social Media Audiences: English and Arabic Twitter Users and Their Networks.” American Behavioral Scientist 57, no. 7 (July 1, 2013): 871–98.

[105] “[Image – 97517] | Bread Helmet Man.” Know Your Meme, 26 Nov. 2014, knowyourmeme.com/photos/97517-bread-helmet-man.

[106] “Bread Helmet Man.” Know Your Meme, 2 Nov. 2017, knowyourmeme.com/memes/bread-helmet-man.

[107] “Bread Helmet Man.” Know Your Meme, 2 Nov. 2017, knowyourmeme.com/memes/bread-helmet-man.

[108] “Bread Helmet Man.” Know Your Meme, 2 Nov. 2017, knowyourmeme.com/memes/bread-helmet-man.

[109] “Programmes – Egypt: ‘We Are All Khaled Said.’” BBC World Service, BBC, www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/programmes/2011/02/110217_outlook_egypt_protests_khaled_said.shtml.

[110] Contributor, Guest. “Digital Media and the Arab Spring.” Reuters, Thomson Reuters, 16 Feb. 2011, blogs.reuters.com/great-debate/2011/02/16/digital-media-and-the-arab-spring/.

[111] Contributor, Guest. “Digital Media and the Arab Spring.” Reuters, Thomson Reuters, 16 Feb. 2011, blogs.reuters.com/great-debate/2011/02/16/digital-media-and-the-arab-spring/.

[112]Adi, Mohammad-Munir. The Usage of Social Media in the Arab Spring : The Potential of Media to Change Political Landscapes throughout the Middle East and Africa. Berlin : Lit, [2014], 2014. Internet economics = Internetökonomie: v./Bd. 8. EBSCOhost, libproxy.berkeley.edu/login?qurl=http%3a%2f%2fsearch.ebscohost.com%2flogin.aspx%3fdirect%3dtrue%26db%3dcat04202a%26AN%3ducb.b21643328%26site%3deds-live.

[113] Alwazir A. Social media in Yemen: expecting the unexpected, Al-Akhbar, 30 December 2011.

[114] Arbatli, Ekim; Rosenberg, Dina (2007). Non-Western Social Movements and Participatory Democracy: Protest in the Age of Transnationalism. Springer International Publishing. pp. 161–170.

[115] The Arab spring, five years on. Charting five years since the onset of the Arab spring. The Economist.

[116] Wikimedia Commons by Faris Knight.<p><a href=”https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Arab_Spring_Protal.gif#/media/File:Arab_Spring_Protal.gif”><img src=”https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/86/Arab_Spring_Protal.gif/1200px-Arab_Spring_Protal.gif” alt=”Arab Spring Protal.gif”></a><br>By <a href=”//commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:Faris_knight” title=”User:Faris knight”>Faris knight</a> – <span class=”int-own-work” lang=”en”>Own work</span>, <a href=”https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0″ title=”Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0″>CC BY-SA 3.0</a>, <a href=”https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17562025″>Link</a></p>

[117] The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. “Prague Spring.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., 28 Oct. 2016, www.britannica.com/event/Prague-Spring.

[118] “Tunisian Revolution.” | Al Jazeera, 15 Dec. 2016, www.aljazeera.com/indepth/inpictures/2015/12/tunisian-revolution-151215102459580.html.

[119] Manfreda, Primoz. “6 Ways Arab Spring Impacted the Middle East.” ThoughtCo, www.thoughtco.com/arab-spring-impact-on-middle-east-2353038.

[120] Manfreda, Primoz. “6 Ways Arab Spring Impacted the Middle East.” ThoughtCo, www.thoughtco.com/arab-spring-impact-on-middle-east-2353038.

[121] Manfreda, Primoz. “6 Ways Arab Spring Impacted the Middle East.” ThoughtCo, www.thoughtco.com/arab-spring-impact-on-middle-east-2353038.

[122] Manfreda, Primoz. “6 Ways Arab Spring Impacted the Middle East.” ThoughtCo, www.thoughtco.com/arab-spring-impact-on-middle-east-2353038.

[123] “Arab Spring Brings Success, Failures.” The Triangle, 26 Feb. 2015, thetriangle.org/opinion/arab-spring/.

[124] “Arab Spring Brings Success, Failures.” The Triangle, 26 Feb. 2015, thetriangle.org/opinion/arab-spring/.

[125] “Arab Spring Brings Success, Failures.” The Triangle, 26 Feb. 2015, thetriangle.org/opinion/arab-spring/.

[126] “Arab Spring Brings Success, Failures.” The Triangle, 26 Feb. 2015, thetriangle.org/opinion/arab-spring/.

[127] “Arab Spring Brings Success, Failures.” The Triangle, 26 Feb. 2015, thetriangle.org/opinion/arab-spring/.

[128] Framing Bouazizi: ‘White lies’, hybrid network, and collective/connective action in the 2010–11 Tunisian uprising