PAGE NAVIGATION

- Introduction

- Context

- Key Actors

- Social Media Presence

- Offline Presence

- Impact of the Movement

- Critiques of the Movement

- Conclusion

Introduction

On Wednesday, April 24th, 2013, an eight-story commercial building collapsed in the Dhaka district in Bangladesh. Referred to as the Rana Plaza garment factory collapse, the accident killed 1,134 garment workers and injured an additional 2,500, making it the deadliest garment-factory disaster in history.[2] Motivated by the tragedy, former fashion designers and founders of Fashion Revolution Orsola de Castro and Carry Somers set out to create a movement that would shed light on the fashion industry’s supply chain and urge people to hold the industry accountable.[3] The #WhoMadeMyClothes hashtag was launched in 2014 and became the number 1 global trend on Twitter. It has received over 156 million impressions online to date.[4] They asked an important question through the hashtag #WhoMadeMyClothes because they wanted consumers to become aware of the brands that they purchase from as well as support brands that do not enslave or endanger workers, have fair pay, and conserve the environment. Since the start of the movement, the founding company Fashion Revolution continues to hold a Fashion Revolution week each year to mark the anniversary of the Rana Plaza disaster and continues to spread awareness surrounding the issue.[5] The movement utilized social media to provide a way to inform people of the injustice in the fashion industry and encourage people to be more cognizant of what they wear. While there were tangible changes in the legislation regarding supply chains and garment industry worker pay, the movement failed to spark a monumental shift in how the fashion industry runs seeing that companies continue to participate in fast fashion.

Name of Movement

The #WhoMadeMyClothes movement was created to inspire consumers to make a change in the fashion industry by holding companies accountable and increasing supply chain transparency. It aligns with people’s current attitudes towards a sustainable future and increased individual activism. By getting consumers to ask the question of where their clothes are produced, it encourages people to take part in the movement and spend a little more time thinking about their own choices in the fashion industry. It also allowed garment workers to contribute to the movement by responding with #IMadeYourClothes, opening up the conversation to both sides of the industry.[6]

The #WhoMadeMyClothes movement addresses a wide range of social issues including the trend towards sustainable fashion and fashion activism, the ethics of supply chains, the issue of fast fashion, human and worker’s rights, and the environmental impact of the fashion industry.

Key Terms

Fast fashion — the concept of producing inexpensive clothing for mass-market retailers to create fashion trends quickly, cheaply, and make them readily available to consumers

Garment factory — a clothing manufacturer

Fashion activism — using fashion to create social change

Child labor — illegally or inhumanely using children in business or industry

Demographics

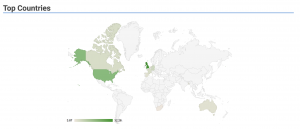

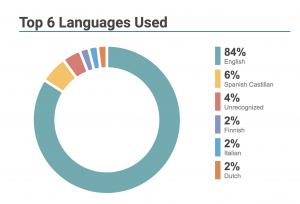

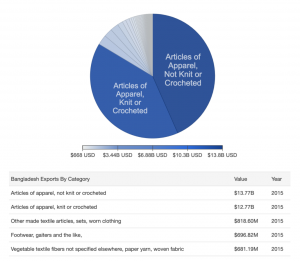

Political Affiliation

#WhoMadeMyClothes has little to almost no political affiliation. However, in Bangladesh, the issue of cheap labor for the garment workers and the lack of safety regulations for the industry are highly political since cheap labor accounts for the majority of the country’s economy. In 2015, apparel exports accounted for 83% of Bangladesh’s total exports.[11]

Key Images

Context

Timeline

On Wednesday, 24 April 2013, an eight-story commercial building in Dhaka called the Rana Plaza collapsed. 1,134 people died and approximately 2,500 people were injured. It is considered the deadliest structural failure accident in modern human history and the deadliest garment-factory disaster in history.

Following the collapse of the Rana Plaza, thousands of garment workers went to the streets of Dhaka to protest. Many of the protesters demanded the death penalty for Sohel Rana, the owner of the building, as well as the owners of the garment factories on the upper floors. More than 150 vehicles were damaged, and protesters burned two factories.

After the Rana Plaza tragedy, the IndustriALL Global Union and the UNI Global Union in alliance with leading NGOs decided to create an accord promoting fashion companies to make efforts to ensure the safety and well-being of fashion workers. Since 2013, the accord has been signed by more than 200 companies from over 20 countries.

Fashion Revolution is a non-profit global movement with teams in over 100 countries around the world campaigning for transparency and change in the fashion industry. Together with the organization, Orsola de Castro and Carry Somers started the #WhoMadeMyClothes campaign through Twitter to bring awareness to the general public.

After a series of protests from garment workers and the critics from the international community, the government of Bangladesh decided to create a three-way negotiation between the labor union, government, and the factory owners to negotiate the raise in garment worker’s wage. Ultimately, on November 24, 2013, the government decided to increase the minimum monthly wage from 3,000 Taka ($38) to 5,300 Taka ($68), effective by January 1, 2014.

On May 29th, 2015, True Cost, a documentary directed by Andrew Morgan and produced by Michael Ross was released. The documentary exposed the true working conditions at various cheap garment factories around the world, including the one in Bangladesh. It discusses various aspects of the garment industry, starting from the production; how the workers are faced with inhumane working conditions, to the aftereffects; pollution and environmental damages caused by the unsustainable manufacturing processes. The movie played a significant role in spreading awareness of the importance of sustainable and ethical fashion.

Following the expiration of the Building and Safety Accord signed in 2013, over 101 brands gather to sign the Transition Accord to ensure that the progress made over the past 5 years will still be maintained in the future. The 2018 agreement currently covers more than 1,200 factories and at least 2 million workers.

After long negotiations between the worker unions, factory owners, and the government, the government decided to increase the salary of garment workers by 51% to $95 per month.

Although the government increased the wage by 51%, the workers deemed the salary still too low to cover their living expenses. The new wage fell short to the demanded monthly wage of $189 proposed by the workers. As a result, workers initiated another protest with over 5000 participants, causing 52 factories across Dhaka to shut down.

Following the expiration of the Bangladesh Accord, European fashion brands who purchased readymade garments from Bangladesh agreed to hand over the responsibility to oversee worker’s safety to the Bangladesh government with its newly made organization called the Readymade Sustainability Council (RSC). The RSC is established by the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA) to ensure a complete and independent national compliance monitoring system in Bangladesh. It will be governed by BGMEA, Bangladesh Knitwear Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BKMEA), brands and workers’ representatives. However, fear began to spread amongst garment workers as they feared that the situation would revert to the conditions before the Rana Plaza incident without the supervision of the international community.

Key Actors

People

Carry Somers

Orsola de Castro

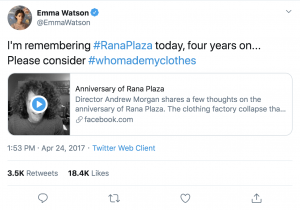

Emma Watson

Organizations

Fashion Revolution

Somers and de Castro launched the #WhoMadeMyClothes hashtag in 2013.[27] The activity of Fashion Revolution and #WhoMadeMyClothes are inseparable. #WhoMadeMyClothes is one of Fashion Revolution’s primary channels to spread awareness about the issue of the unethical fashion manufacturing process.

IndustriALL Global Union

After the Rana Plaza incident in 2013, IndustriALL Global Union along with the UNI Global Union and several other NGOs stepped in to fight for labor rights and industry regulation reforms in Bangladesh. The organization played a vital role in establishing the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh, the accord which requires fashion companies to make efforts to ensure the safety and well-being of fashion workers.[30] After the expiration of the accord, IndustriAll Global Union also proposed a transition accord in 2018, called the 2018 Transition Accord to continue the progress and changes brought by the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh.[31]

International Labour Organization

Social Media Presence

The company Fashion Revolution created the #WhoMadeOurClothes movement to spread awareness for the tragedy that happened at Rana Plaza. Their first media outreach was ignited in Berlin in 2015 when Fashion Revolution placed an interactive photo booth promoting a bargain of “T-shirts for 2 Euros.” As people went up to the booth to insert their coins, a video automatically played displaying who was responsible for making the T-shirt and the history of cheap/fast fashion. At the end of every clip, the photo booth proceeded to ask whether they would still like to buy the T-shirt for 2 Euros or donate the money instead. Everyone who watched donated. This experiment was posted on Fashion Revolution’s Youtube channel, reaching 7 million views, and was the catalyst for the #WhoMadeOurClothes movement.[35] They proceeded to start campaigns through social media platforms including Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. In 2016, they reached 129 million people through social media campaigns and activities.[36] Fashion Revolution utilized Instagram by posting photos that challenged users to demand answers from fashion companies like Zara and H&M by using their hashtag on social media and directly emailing fast fashion companies.

Popular Hashtags

#WhoMadeMyClothes

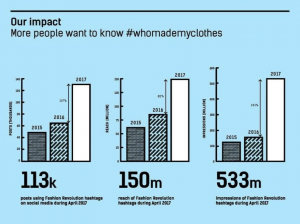

The first and main hashtag that has been used in the social media movement is #WhoMadeMyClothes. This hashtag was created the first year Fashion Revolution was founded (2013) in order to spread awareness for a fairer, safer and more transparent fashion industry.[38] In April 2018, this hashtag brought 720 million impressions to the movement which was a 35% increase from the previous year. There were 173K posts with the tag #WhoMadeOurClothes in 2018 with a reach of 275 million.[39]

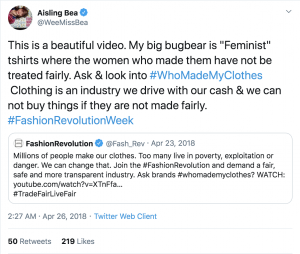

In response to #WhoMadeOurClothes, brands and retailers started to respond to the movement with the hashtag #IMadeYourClothes.[41] #IMadeYourClothes was also tagged in many posts representing the harsh working conditions of many workers. This hashtag was first presented in 2016 and was able to reach 3500 producer voices within the first year.

In 2016, Fashion Revolution made another hashtag to spread awareness of their social movement named #HaulAlternative. #HaulAlternative was mainly targeted towards youtube watchers and creators to post a video of refreshing their current wardrobes instead of buying new clothes. This was inspired by traditional fashion hauls where individuals buy clothes and show off their new pieces. Instead, this hashtag started a conversation around why reusing and refreshing current pieces is better. This hashtag resulted in 3.11 million views of Fashion Revolution in 2016. #HaulAlternative project continued to grow throughout the years and in 2018 Kristen Leo’s Thrift Store Haul was viewed by 32,000 people and inspired over 70 high profile vloggers around the world to make their own videos.[43]

#FashionRevolutionWeek

#FashionRevolutionWeek was one of the first hashtags used during Fashion Revolution week during April 23-29 (anniversary of Rana Plaza Collapse).

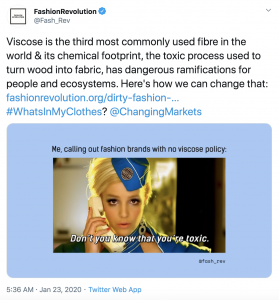

Memes

Analysis

Social Media has played a vital role in the #WhoMadeMyClothes movement. The hashtag sparked consumer’s curiosity about the humanitarian and global aspects of the fashion world. Before, many consumers were not aware of the detriments in the fashion industry supply chain and the negative externalities of fast fashion. Fashion Revolution gave consumers a platform to ask about where their clothes came from and brought about a conscious effort to make a difference in the industry. Social media has also had an important role in this movement because it has allowed brands and companies to directly interact with their consumers. By responding with #IMadeYourClothes, brands can show consumers that they are passionate about the issue and want to provide transparency. In addition, the growth was very organic and founders Castro and Somers were unaware of how much the movement would catch and attract attention. What was first was a campaign to raise awareness ended up being a social media movement. As the movement online continued to grow, Fashion Revolution was able to increase their offline presence as well by pairing up with policymakers, partnerships, and student ambassadors to continue to spread awareness.

Offline Presence

Fashion Revolution has taken its strong online presence and turned to events and partnerships to expand its mission of awareness. As mentioned before, they are present offline in many categories including partnerships, student ambassadors and partnering with policymakers.

Partnerships and Events

One partnership that Fashion Revolution took part in was Earth Day in 2019. They partnered with Extinction Rebellion to highlight fashion’s place in the climate emergency ( Global Fashion Exchange, World Economic Forum). Fashion Revolution has over 500 global partnerships, 300 of them with NGOs and activist groups, 200 of them with educational organizations. Another partnership fashion revolution has done in the past is with Global Fashion Exchange. GFX and Fashion Revolution partnered with each other to produce a Global Swap event where consumers came and swapped their old clothes with others. The point of this event was to start a discussion on how consumers can change their habits by reevaluating the way they shop. In this event they were able to spread the knowledge on how increasing a clothes life by 9 months can actually lead to a reduction of 20-30% in carbon footprint.[50] Fashion Revolution has been able to host around 1000 events in the time they have started until now in order to spread their awareness.

Impact of the Movement

Policy Achievements

Since the start of Fashion Revolution, they have worked to fight for regulations that support the movement through the political sphere. Fashion Revolution has continuously partnered with government officials and committees as well as other nonprofit organizations to make an impact to fight for sustainable initiatives and systemic changes in the global fashion industry.

Reinforcing the UK Modern Slavery Act of 2015 was one of the biggest impacts they contributed to. In 2015, the UK Parliament passed the Modern Slavery Act, requiring big brands to explain what they were doing to tackle modern slavery within their supply chain.[51] While Fashion Revolution positively impacted this legislation, the Act did not create a central registry list to keep these brands accountable. However, in 2019, Fashion Revolution, in partnership with Traidcraft, asked the public to sign a petition to urge the UK government to do more than pass the 2015 Act. In response, the government compiled a commitment to launch an online registry that shows which companies are compliant with the law.

In February 2019, the UK Government’s Environmental Audit Committee released Fixing Fashion, a report highlighting evidence from global fashion retailers, supply chain experts, and environmental leaders on what the sustainability climate of the UK fashion industry looked like. Based on the evidence, The Committee urged the government to take action on the recommendations given from the report to help with the known social and environmental abuses happening because of the production, purchasing, and disposal of clothing. While the UK government’s ministers rejected all of the recommendations due to their desire to keep existing voluntary non-regulatory approaches, Fashion Revolution continues to work with the Environment Audit Committee to lobby for the reconsideration of the Government’s decision.

Other Achievements

The impact of the Fashion Revolution movement was not only within the political sphere or through policy reform. General awareness from the public about this movement, especially through social media, has grown significantly. To mark the 5th anniversary of Rana Plaza, Fashion Revolution created a campaign video in 2018 for #WhoMadeMyClothes.[52] The campaign video gained popularity globally, reaching more than 850,000 views and was a key approach to spreading awareness about the movement. During the annual Fashion Revolution week in 2018, the organization hit record numbers in terms of their reach. The movement reached 35% more individuals than the previous year in their social media presence and outreach. The hashtags, such as #WhoMadeMyClothes, used during the week of the Fashion Revolution movement, mobilized the reach from 150 million people in 2017 to 275 million in 2018 worldwide.

The significant increase in general awareness further incentivized global fashion brands to increase their transparency as a brand. In the 2018 Transparency Index, it was revealed that many of the global fashion brands only disclose little information on the workers within their supply chains. The Index provided an opportunity for these global fashion companies to change and even justify what exactly was happening within their supply chain. As of June 2018, about 172 brands across 68 countries began to reveal more information. In response to the hashtag, #WhoMadeMyClothes, more than 3,838 global brands also took to social media to respond with real information about their suppliers and workers.

Critiques of the Movement

Some brands are criticizing the methodology Fashion Revolution used to create the Transparency Index, an essential document of information that provides much of the leverage to get global brands to work with the cause.[53] They indicate that it is built on showing more of a brand’s communication policies rather than their social and environmental responsibilities.

Fashion Revolution’s co-founder Orsola de Castro responded to their criticism by indicating that the Index created does measure each brand’s communication with consumers about their supply chain. However, she also states that part of a brand’s obligations and responsibilities is their communication with consumers, especially on informing them how the product they purchase is made. De Castro admits that the Transparency Index is not perfect, but that if brands have good relationships with who they work with, it should be something that is shared and celebrated with Fashion Revolution.

Conclusion

The Fashion Revolution movement is still making an impact through the use of #WhoMadeMyClothes annually. The nonprofit organization behind the movement has a global network with volunteers all over the world, especially in the fashion industry, who spread awareness whether it is creating hashtag activism on social media, developing partnerships to create strategies for change, or building reports such as the Transparency Index. This movement continues to fight through three central areas. First, it is building over 500 partnerships that help build case studies on how and why the movement is important. Second, the movement continues to collaborate with 112 participating policymakers that actively advocate for Fashion Revolution in governmental space. Lastly, one of the biggest components of the movement is hosting the Annual Fashion Revolution week each April to boost awareness and increase people’s participation each year.

Author Biographies

Lindsay Timmerman | ltimmerman@berkeley.edu | www.linkedin.com/in/lindsay-timmerman

Lindsay is a third-year UC Berkeley student majoring in Business Administration and Economics. She is passionate about reducing economic inequality with a long-term career goal of increasing educational access for young girls in developing countries. When she’s not studying, you’ll find her in a yoga class or exploring the Bay Area.

Winnie Zhou | winnie.zhou@berkeley.edu | https://www.linkedin.com/in/winnie-zhou

Winnie is a fourth-year UC Berkeley student studying Media Studies (Mass Communications) and Public Policy. She is passionate about environmental sustainability with a long-term future goal to work in corporate social responsibility. When she’s not working or studying, you can find her on traveling and eating adventures around the Bay Area and across the globe.

Stanford Anwar | stanford15_@berkeley.edu | www.linkedin.com/in/stanford-multi-anwar/

Stanford is a third-year UC Berkeley student studying Business Administration and Data Science. He is passionate about the intersection between technology and business and how business can be utilized as a channel to impact society. When he’s not studying, you will find him playing badminton or exploring foods across the Bay Area.

Malika Mirbagheri| malikamirbagheri@berkeley.edu|www.linkedin.com/in/malikamirbagheri/

Malika is a third-year UC Berkeley student studying Business Administration. Her passions include Marketing, Data Analytics, and Fashion. She is also passionate about the sustainability movement behind fashion industries and how the future is changing. Malika’s dream job would include working for a media or fashion company in Marketing Analytics. When she is not studying she is watching fashion and makeup videos on YouTube or filming TikToks.

Sources

[1] Yardley, Jim. “Report on Deadly Factory Collapse in Bangladesh Finds Widespread Blame.” The New York Times, 23 May 2013, Accessed 4 Mar. 2020. www.nytimes.com/2013/05/23/world/asia/report-on-bangladesh-building-collapse-finds-widespread-blame.html.

[2] ibid.

[3] Omotoso, Moni. “‘Who Made My Clothes’ Movement – How it All Began.” Fashion Insiders, 5 Dec. 2018, Accessed 4 Mar. 2020. fashioninsiders.co/features/inspiration/who-made-my-clothes-movement/.

[4] Egenhoefer, Rachel Beth. Routledge Handbook of Sustainable Design. Routledge, 2017.

[5] Blanchard, Tamsin. “Fashion Revolution Week: Seven Ways to Get Involved.” The Guardian, Guardian News, 24 Apr. 2018, Accessed 4 Mar. 2020. www.theguardian.com/fashion/2018/apr/24/fashion-revolution-week-seven-ways-to-get-involved.

[6] Omotoso, Moni. “‘Who Made My Clothes’ Movement – How it All Began.” Fashion Insiders, 5 Dec. 2018, Accessed 4 Mar. 2020. fashioninsiders.co/features/inspiration/who-made-my-clothes-movement/.

[7] “Results for: #whomademyclothes.” Hashtagify, Accessed 14 Apr. 2020. hashtagify.me/hashtag/whomademyclothes.

[8] ibid.

[9] ibid.

[10] ibid.

[11] “Bangladesh Exports By Category.” Trading Economics, 2019, tradingeconomics.com/bangladesh/exports-by-category.

[12] ibid.

[13] “Home.” Fashion Revolution, www.fashionrevolution.org/.

[14] Emma. “Https://Www.milouandpilou.com/i-Made-Your-Clothes/.” Milou & Pilou, Milou & Pilou, 4 May 2018, www.milouandpilou.com/i-made-your-clothes/.

[15] Yardley, Jim. “Report on Deadly Factory Collapse in Bangladesh Finds Widespread Blame.” The New York Times, 23 May 2013, Accessed 4 Mar. 2020. www.nytimes.com/2013/05/23/world/asia/report-on-bangladesh-building-collapse-finds-widespread-blame.html.

[16] ibid.

[17] “Berliner Game Changer for More Sustainability in the Fashion Industry.” Berliner Game Changer for More Sustainability in the Fash | Berlin Fashion Week, 13 Sept. 2019, fashion-week-berlin.com/en/blog/single-news/berliner-game-changer-for-more-sustainability-in-the-fashion-industry.html.

[18] ibid.

[19] 2018, 4 July. “My Fashion Life: Carry Somers, Co-Founder of Fashion Revolution.” Drapers, www.drapersonline.com/people/my-fashion-life/my-fashion-life-carry-somers-co-founder-of-fashion-revolution/7030877.article.

[20] ibid.

[21] “Fashion Revolution: All We Should Know, by Orsola De Castro – Luxiders.” Sustainable Fashion – Eco Design – Healthy Lifestyle – Luxiders Magazine, 31 Jan. 2018, luxiders.com/fashion-revolution-orsola-de-castro/.

[22] ibid.

[23] Watson, Emma. “I’m Remembering #RanaPlaza Today, Four Years on… Please Consider #WhomademyclothesT.co/KtIgR86qEc.” Twitter, Twitter, 24 Apr. 2017, twitter.com/EmmaWatson/status/856612150357499905.

[24] “ABOUT.” Fashion Revolution, www.fashionrevolution.org/about/.

[25] ibid.

[26] ibid.

[27] Blanchard, Tamsin. “Who Made My Clothes? Stand up for Workers’ Rights with Fashion Revolution Week | Tamsin Blanchard.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 22 Apr. 2019, www.theguardian.com/fashion/commentisfree/2019/apr/22/who-made-my-clothes-stand-up-for-workers-rights-with-fashion-revolution-week.

[28] “Who We Are.” IndustriALL, 21 June 2019, www.industriall-union.org/who-we-are.

[29] ibid.

[30] “More than 100 Brands Sign 2018 Transition Accord in Bangladesh.” IndustriALL, 14 Feb. 2018, www.industriall-union.org/more-than-100-brands-sign-2018-transition-accord-in-bangladesh.

[31] ibid.

[32] “Mission and Impact of the ILO.” Mission and Impact of The, www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/mission-and-objectives/lang–en/index.htm.

[33] ibid.

[34] @ilo (International Labour Organization).”The ILO has been asking #WhoMadeMyClothes since 1919! Find out more: http://bit.ly/2CQkPr8 #ILO100“. Twitter, February 11 2019, 6:00 a.m., https://twitter.com/ilo/status/1094959316354977799.

[35] “The 2 Euro T-Shirt – A Social Experiment.” YouTube, 23 Apr. 2015, www.youtube.com/watch?v=KfANs2y_frk&feature=emb_logo.

[36] “The consumer can make a difference.” Fashion Revolution, https://www.fashionrevolution.org/the-consumer-can-make-a-difference/

[37] “2018 Impact.” Fashion Revolution, https://www.fashionrevolution.org/2018-impact/

[38] Omotoso, Moni. “‘Who Made My Clothes’ Movement – How it All Began.” Fashion Insiders, 5 Dec. 2018, Accessed 4 Mar. 2020. fashioninsiders.co/features/inspiration/who-made-my-clothes-movement/.

[39] “2018 Impact.” Fashion Revolution, www.fashionrevolution.org/2018-impact/.

[40] ibid.

[41] “Get Involved.” Fashion Revolution, https://www.fashionrevolution.org/about/get-involved/

[42] @Fash_Rev (Fashion Revolution).”Download an ‘I made your clothes’ poster here: http://ow.ly/10DfBF“. Twitter, April 14 2016, 3:01 a.m., https://twitter.com/Fash_Rev/status/720552497463566336

[43]“HUGE 70’s Thrift Haul! 🌈 Designer Brands, PRADA & more #haulternative.” YouTube, 21 Mar. 2018,

youtu.be/e7n9Plg3HQ8.

[44] @WeeMissBea. “This is a beautiful video. My big bugbear is “Feminist” tshirts where the women who made them have not be treated fairly. Ask & look into #WhoMadeMyClothes Clothing is an industry we drive with our cash & we can not buy things if they are not made fairly. #FashionRevolutionWeek” Twitter, April 26 2018, 2:27 a.m., https://twitter.com/WeeMissBea/status/989435861124177920

[45] “Wear your clothes inside out for Fashion Revolution Day.” The Guardian, www.theguardian.com/fashion/gallery/2015/apr/24/wear-your-clothes-inside-out-fashion-revolution-day.

[46] “#Insideout – Six Months On.” Fashion Revolution, Fashion Revolution, 2015, www.fashionrevolution.org/uk-blog/insideout-six-months-on/.

[47] FashionRevolution. Twitter, Twitter, 23 Jan. 2020, twitter.com/Fash_Rev/status/1220339545234907136.

[48] FashionRevolution. “This #FashionRevolution Week, from the 20th to the 26th of April 2020, We’re Joining Forces with @GFX_change to Make the Largest Swap in History and We Need Your Help to Do It. Register Your Interest and Stay up to Date! #ClothesSwap #LovedClothesLastT.co/l9cZfzVcb6 Pic.twitter.com/jTtF86rJRs.” Twitter, Twitter, 6 Dec. 2019, twitter.com/Fash_Rev/status/1202958649217433605.

[49] Person, and ProfilePage. “Fashion Revolution on Instagram: ‘The New Year Often Brings about Reflection, Goal Setting, and a Figurative Clean Slate. But When Marketing Messages Get Ahold of That…”.” Instagram, www.instagram.com/p/B60IF9YhUDl/?igshid=lsmshwduiixa.

[50]“Global Swap with Fashion Revolution 2019.” Fashion Revolution, www.fashionrevolution.org/global-swap-with-fashion-revolution-2019/.

[51] Fashion Revolution. “Fashion Revolution Impact Report 2019.” Issuu, 3 Oct. 2019, issuu.com/fashionrevolution/docs/fashionrevolution_impactreport_2019_highres.

[52] “2018 Impact.” Fashion Revolution, www.fashionrevolution.org/2018-impact/.

[53] Theodosi, Natalie. “Fashion Revolution Responds to Criticism From Brands on Its Transparency Index.” WWD, Penske Media Corporation, 29 Apr. 2016, wwd.com/fashion-news/fashion-scoops/fashion-revolution-criticism-transparency-index-chanel-fendi-sustainability-10421031/.

sugar stoned edibles

Really like your way of writing a blog. Keep up the great work !

Доступные решения – цена ликвидации ООО в Москве и области в 2022 году. Ознакомьтесь – стоимость ликвидации ООО, официальная и альтернативная. ☎ +7 (499) 714-86-84

I gotta favorite this website it seems very helpful .

I gotta favorite this website it seems very helpful .

https://bit.ly/3JKKMKg

limoncello strain

Really like your way of writing a blog. Keep up the great work !

GK Questions is India’s best website for exams like NDA, CDS, IAS, SSC, PCS/PSC, IBPS Banking, UPPCS, Bihar PCS, MPPSC, RPSC, SSC-CGL.

สล็อต Wallet What is an outstanding post! “I’ll be back” (to read more of your content). Thanks for the nudge!

Kıbrıs’a geleceksin ve eğlenmek istiyorsun nereye mi gideceksin? Kıbrıs Gece Kulupleri her şeyi senin için organize ediyor.

hunza valley

good content everywhere i like it

Superbly written article, if only all bloggers offered the same content as you, the internet would be a far better place.. สูตร สล๊อต

amazon delivery

This is a great website. Keep posting!

Aria Akbari – “Man Hanoz Doset Daram” > Old Song > Download With Text And 320 & 128 Links In Musico

thansk to share article

Kiralık bahis siteleri özel yazılım hizmetleri adminlik ve bayilik.Sizinde bir bahis sitesi olsun isterseniz bu alanda kiralık bahis sitesi için bağlantıya tıklayınız.

I needed information about this movement that I was able to get from your site. Thank you very much for your good content.

Thanks for sharing, this is a fantastic article.

Thanks so much for sharing this post

hunza valley

If you are having questions about which คาสิโนออนไลน์ website is the best? and looking for the web แทงบอลออนไลน์ Good to play on the website DUCKBET is the answer. We are a website that has a comprehensive online betting service. whether it is online football betting Online casino, the best price, we are สมัครduckbet direct website from the parent company. not pass agent Eliminate the problem of cheating More confident with fast service Financial stability, deposit-withdraw within 1 minute with automatic system So our website now Become the No. 1 in online gambling website provider duckbet at this time.

very good

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been given a no. Only to find that a better, brighter,샌즈카지노 bigger yes was right around the corner.

thanks a lot

موضوع اصلی : میکروبلیدینگ ابروی آقایان چه مزایایی دارد

میکروبلیدینگ ابروی آقایان ، خطوط هاشور به صورت نامنظم و با طول های نامساوی در لابه لای موی ابرو ایجاد میکند ، بنابراین نمای ظاهری این تکنیک طبیعی تر از سایر تکنیک ها خواهد بود.

خراش های ایجاد شده در این تکنیک در سطح پوست بوده و به همین دلیل میزان خونریزی در این تکنیک بسیار کم است.

طراحی ابرو با این روش، معمولا ۲ ساعت طول میکشد.

افرادی که باردار هستند، مستعد ابتلا به کلوئید هستند و یا پیوند عضو انجام داده اند. نباید این روش را انجام دهند.

اگر شما بیماری کبد خطرناکی دارید یا یک بیماری ویروسی مثل هپاتیت دارید.باید قبل از انجام این روش حتما به تکنسین خود اطلاع بدید و این کار را با احتیاط انجام بدهید.

برای انجام این روش ، در آرایشگاه داماد : مهارت و تخصص پیگمنتر و استریله بودن سوزن های ابزار این روش از قبل بررسی شده تا از عوارض این کار در امان باشید.

اگر شما نگران روند دردناک این روش هستید، باید بدانید که قبل از شروع میکروبلدینگ، یک کرم خفیف موضعی برای به حداقل رساندن ناراحتی شما استفاده خواهیم کرد،که دردی احساس نکنید.

to pull out of a country that’s become a global outcast as companies seek to maintain their reputations and live up to corporate responsibility standards.

Investors were drawn to Russia in search of lucrative profits they thought were worth the geopolitical risks

You basically have Russia becoming a commercial pariah,” said economist Mary Lovely, a senior fellow

at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington. “Pretty much no company, no

multinational, wants to be caught on the wrong side of U.S. and Western sanctions

Oil and gas companies, already feeling the heat from climate activists to invest in renewable energy, were among companies to announce the most rapid and dramatic exits.

ExxonMobil said it will pull out of a key oil and gas project and halt any new investment in Russia. All their chief executives

thank you

This is a great article. Thanks for the info.

Your post is very helpful to me. Thank you.

Organic Honey

Wao what an article! Thankyou for getting boosted

Dota 2 boosting

There are a lot of blogs over the Internet. But I can surely say that your blog is amazing in all. It has all the qualities that a perfect blog should have. บาคาร่าวอเลท

Thanks, that was a really cool read! บาคาร่าวอเลท

hello!! Very interesting discussion glad that I came across such informative post. Keep up the good work friend. Glad to be part of your net community. สล็อตเว็บใหญ่

Wao what an article! Thankyou for getting boosted

QlickBank #1 Exclusive Affiliate Marketing Network for 2022. Best Affiliate Programs For Publishers. Either As An Advertiser Acquire More Customers Today! Set Your Affiliate Marketing Goal with Qlick Bank – A Trade to Develop Performance Based Advertising for Advertisers / Vendors / Online Sellers.

This is the very nice blog

Thank You for sharing this amazing blog

Hey,

Thank for sharing this blog. Keep sharing

Thank you for sharing this informative blog

This is an amazing blog. Thank for sharing with us. Keep sharing informative blogs

Thank You So Much. Best Web Hosting Plan

thanks

I like viewing web sites which comprehend the price of delivering the excellent useful resource free of charge. I truly adored reading your posting. Thank you!

Looking for a CASUAL RELATIONSHIP or ONLINE HOOKUP, read out the prefer to have material, qualities or hobbies for your hookup partner. Just logon to lustrous.fun and get the perfect partner for your next CASUAL HOOKUP IN YOUR CITY.

If you want to be successful in weight loss, you have to focus on more than just how you look. An approach that taps into how you feel, your overall health, and your mental health is often the most efficient. Because no two weight-loss journeys are alike, we asked a bunch of women who’ve accomplished a major weight loss exactly how they did it 먹튀사이트

Very interesting blog. Agario is a fun game even if you are just starting out but you are always better off when you know what to expect and how to maneuver your way around so you can survive for as long as possible. Here are just a few tips that can help boost your survival rates as you enjoy the game..Positive site, where did u come up with the information on this posting?I have read a few of the articles on your website now, and I really like your style. Thanks a million and please keep up the effective work 더킹카지노

Very likely I’m going to bookmark your blog . You absolutely have wonderful stories. Cheers for sharing with us your blog..Thank you for such a great article..Wow, excellent post. I’d like to draft like this too – taking time and real hard work to make a great article. This post has encouraged me to write some posts that I am going to write soon 토토사이트

Thank you a bunch for sharing this with all of us you actually realize what you are talking about! Bookmarked..Great webpage brother I am gona inform this to all my friends and contact..Wonderful illustrated information. I thank you about that. No doubt it will be very useful for my future projects. Would like to see some other posts on the same subject 안전카지노

Terrific article! That is the kind of information that are meant to be..shared across the internet. Disgrace on the search engines.together with everyone’s favorite activity, sex.Two foot fetish guys, one of which wanted me to smear peanut butter on my feet. 안전공원

Guitar Amp Input Jack The Guitar Amp Input Jack is a device that allows the signal from a guitar to be passed through to an amplifier. This product is ideal for live performance or recording, and it is compatible with most amps. The Guitar Amp Input Jack is constructed from a high-quality plastic, and it features a durable plug. How to Fix Guitar Amp Input Jack?

Do the victims and their bereaved families receive assistance or compensation?

thanks for posting

and are among those who have been

warning from British Prime Minister Boris

mir Putin: Invade Ukraine and there will be “significan

Three days after that phone call last Dec. 13, Johnson

pment bank VEB, whose assets Britain fro

is far from alone. Lubov Chernukhin is just one of

Nice post! As I see, your writing style is great, without grammatical mistakes. You are doing a great job, so keep it up! If you want to read about co2 bags for grow tents, our team comes with the best products for you. Click here and read more information about this topic. Make indoor gardening easier right now with just one click!

خرید برنج هندی عمده

خرید فیجت

خرید میز بیلیارد

پنل دیوارپوش

خرید دوربین موبایل

The content you share is really helpful for me. I hope you will provide more great information.

visit us the best merchandise for the polo g collection of all seasons.

เล่นเกมออนไลน์เพื่อความบันเทิงไปแล้ว ลองมาเล่นเกม แล้วได้ทั้งความบันเทิง แะเงินรางวัลกับเว็บของเรา https://ambbet.game ที่มีเกมสล้อตให้เลือกเล่นง่าย ๆ กติกาไม่ยากเท่าเกมอื่น ๆ เพียงเงิน 10 บาท ก็เล่นเกมอย่างต่ำ 10 รอบแน่นนอ แต่ถ้าสมัครวันนี้ พร้อมฝากยอด 100 บาท รับเครดิตเพิ่ม 200 บาท ทันที สำหรับสมาชิกรายใหม่ เล่นเกมโยเงินรางวัลได้เลย

lead generation

good information انواع لنز گوشی موبایل

You can click hereto see good information like this page

yes like https://www.isna.ir/news/1400121410219/نکات-مهم-در-راهنمای-خرید-قطعات-موبایل

thank you for post

دیوارپوش بیمارستانی کجا استفاده می شود

قیمت دستگاه تصفیه آب به روش اسمز معکوس

پوکه معدنی چگونه مانع از اتلاف انرژی در ساختمان می شود

https://pke-buy.com/fa/مقالات/همه-چیز-در-مورد-پوکه-معدنی

هرچیزی که باید در مورد ترمیم کننده زخم بدانید را در مقاله زیر بخوانید:

کرم ترمیم کننده چیست

You have really creative ideas. It’s all interesting I’m not tired of reading at all.

sagame777s เว็บไซต์ข้องเราได้รวมเอาข่าวสารเกี่ยวกับเกมเดิมพันออนไลน์ที่น่าติดตามมารวมไว้ที่นี่เเล้ว !! คลิกได้เลยที่นี่ รวมทั้งยังมีเทคนิคในการทำเงินเกมเดิมพันที่ครบครันไม่ว่าจะเป็น สล็อต บาคาร่า คาสิโน เกมยิงปลา เรามีหมด สูตรที่มีความเเม่นยำสูง ใช้ได้กับค่าย ทุกเกม รับรองว่ารับทัพรย์เข้ากระเป๋ารัวๆ อย่างเเน่นอน.

We will recommend and introduce each Toto site that suits the characteristics of each company and members. Make high profits through our eating tiger.

The small tease of Greta Gerwig’s Barbie movie that Warner Bros. دانلود فیلم shared this week — a still image of Margot Robbie all dolled up and driving a dream car — singlehandedly put the project at the back front of people’s minds as something they might actually want to see.

Situs Hiburan Taruhan Terfavorit Saat Ini

Mari kunjungi link daftar kami ; Bonanza138

Entrance to online slots game website, modern matching game, new format, easy to understand Ak88king

ccording to the Treasury’s press release, Blender.io was used by the Lazarus hacking group to launder $20.5 million worth of the cryptocurrency it allegedly stole from the crypto-based game Axie Infinity. The entire proceeds of the hack, which the Treasury linked to Lazarus and North Korea in April, were estimated to be worth around $625 million at the time, though a few million dollars worth of funds have been recovered. The Treasury says that Lazarus is sponsored by North Korea’s government and that the country uses hackers to “generate revenue for its unlawful weapons of mass destruction (WMD) and ballistic missile programs.”

Entrance to online slots game website

Entrance to online

The entire proceeds of the hack, which the Treasury linked to Lazarus and North Korea in April, were estimated to be worth around $625 million at the time, though a few million dollars worth of funds have been recovered…

istanbul hurdacı sitesi hurda alımı

embedded in a field. Remnants of other devices lay scattered in the village.

jagged pieces of shrapnel. A farmer raked over a small crater left by an explosion in his potato field.

t woke up the children. In tears, 7-year-old Maksym hid under his blanket. His twin sister K

This was one of the things I really wanted.

very good and Thanks for share

embedded in a field. Remnants of other devices lay scattered in the village.

Provide a choice of fun games and provide great prizes to players…

Let’s visit our website immediately:

Bonanza138

Thanks for sharing, Forklift Certification Ontario.

thank you

خرید ظرف پخت پیتزا

Yes, hearing about this tragedy. My condolences to everyone who has experienced this in one way or another. Unfortunately, such events occur and the saddest thing is that we cannot influence this in any way. The only thing we can do is change our attitude towards the situation, if we cannot influence it in any way. A friend from video chat with girls taught me this wisdom a couple of years ago, and over time, I realized that this is the only thing we can do, because with experiences nothing can be changed.

Aside from the main services usually offered by warehouses, there are other additional services offered as part of the package.

Full of fun and ease in playing the game.

slot gacor Bonanza138

Offering promotions and experiences you never get anywhere else.

Buy budget weed online in Canada now and explore various strains like Sunset Sherbet strain. Huge selection of Budget Buds and Bulk Concentrates!

Great post after a good read I like to smoke and relax, check out various strains such as Green Poison strain it’s one of my favorite budget buds!

They have a huge selection of bulk concentrates.

Looking for budget bud cannabis in Canada? Explore various strains such as Dark Star strain. Huge selection of budget buds and bulk concentrates!

good well

สล็อต1688

good well

บาคาร่าเว็บตรง

Thanks for sharing excellent informations.

hitenchaudhary

Good time

that was perfect

It was the best

It was the most beautiful

Hi

that was perfect

Thank you for the beautiful writing

Good luck

Hi

The material was very useful

Thank you for this useful and valuable material

The best thing I’ve read, Thank you so much.

This article is very valuable and I thank you

vape modules from famous brands, they’re all here.Long-term stable supply, holiday discounts, regular discount code issued.dead rabbit r tank

شرکت آبگونه پالایش گستر نوین ، فروش انواع

دستگاه تصفیه آب خانگی

شرکت آبگونه پالایش گستر نوین

خرید دستگاه تصفیه آب

و پیش تصفیه ، فروش انواع آب تصفیه کن خانگی

آبگونه پالایش گستر نوین مرکز فروش انواع دستگاه تصفیه آب خانگی ، نیمه صنعتی و پیش تصفیه در ایران ؛

دستگاه تصفیه آب

ape modules from famous brands, they’re all here.Long-term stable supply, holiday discounts, regular discount code issue

Thank you for allow me to comment in here

sexy สล็อต

What an amazing website thank you for permitting me to comment keep it up

Thank you very much for this extraordinary information.

Purchase weeds online in Canada now and explore various strains such as Skywalker strain

Buy Canadian cannabis online now and explore various strains such as Northern Lights strain

Looking for Canadian cannabis? Explore various strains like Sunset Sherbet strain

Buy Canadian cannabis online now and check out various strains such as Green Poison strain

Looking for budget cannabis in Canada? Explore various strains such as Dark Star strain

Great article! After a good quality read I like to ingest cannabis, check out various strains such as Biscotti strain. They have great prices to fit any Budget.

Great post while I’m reading, I like eat some edibles, check out various THC edibles such as Shipwreck Edibles Blueberry is my favorite.

Great article! After a good read I enjoy unwinding with cannabis. Explore various strains such as Purple Diesel strain. They have a huge selection of budget buds and CBD products.

Thank you very much

This is an excellent guide, thanks for posting it. Succeed! It could be one of the most useful blogs

We have ever come across the subject.

twenty one pilots hoodie Excellent info! I’m also an expert on this topic so I can understand your effort very well. Thanks for the huge help. buy cheap if likes

This is just the information I am finding everywhere. Thanks for your blog, I just subscribe to your blog. This is a nice blog

donda merch

Ground Report believes CLIMATE CHANGE should be the basis of current disclosure, and our stories attempt to reflect the same. And “GROUND REPORT ALSO PROVIDES PAID BACKLINKS, PAID AND PROMOTIONAL ACTIVITIES AND MORE SERVICES ON OUR WEBSITE. WE OFFER YOU VERY AFFORDABLE AND LOW PRICE ADVERTISEMENTS ON OUR PLATFORM.”

thanks for sharing

Great post while I’m reading, I like eat some edibles, check out various THC edibles such as Shipwreck Edibles Blueberry is my favorite.

https://herbapproach.org/product/death-bubba-strain/

Excellent blog. Wow this blog is very nice …

wonderful hashtags topics.All the topics are relatable and awaring to save this planet for the future generation.

movers and packers in Bangalore

Of course, the shape and size will have an immediate effect on the number, type and placement of your fluid mixers. Spanish Sound Editor NY

Địa chỉ mua băng keo Bình Dương giả sỉ tận xưởng. Giao hàng nội thành miễn phí. Xuất VAT và có công nợ cho công ty

Mua màng PE Bình Dương ở đâu giá rẻ và chất lượng nhất?

Băng keo in logo in chữ giá rẻ số lượng ít theo yêu cầu tại Bình Dương, TPHCM 2022

Im loving your website, its really dope. Its good to relax after a long time with cannabis, especially my favourite indica strain11 week Pink kush Strain Review

بیلجبیحلمیبحلیبجلئیبخلئیبحئلب

اقامتگاه در هرمز

I gotta favorite this website it seems very helpful .

Açıklanan verilere göre son yıllarda E-ticaret hacmi yüzde yüzün üzerinde arttı. İnsanlar birkaç tık ile alışveriş yapabilmenin kolaylığını yaşıyor ve bu durumda satıcıları internet dünyasına yönlendiriyor. Adana E-Ticaret ile e-ticaret sitesi sahibi olabilir ve markanızı dijital dünyaya taşıyabilirsiniz.

hash weed

Simple but very precise info. Keep up the good work!

دانلود جدید ترین موزیک ها در سارو موزیک

what is thc distillate

This is something worth reading kind of article.

.یببیولجیبگلوبیگل

کافه در هرمز

جسحیویثجلویبلاولحماو

اقامتگاه در هرمز

changed to increase inclusiveness and recognition https://archive.org/details/increase-rank

Life is something, we should cherish

We never know, when we’ll perish

Live each and every single day

Smell the flowers, stop and play

Life is something, we’ve been blessed

Choice is yours, choose your quest

Follow your passions, and you’ll be fine

With the right attitude, you will shine

https://herbapproach.com/product/purple-cheese/

I like the value information you provide in your article. Right here I appreciate all of your extra efforts. Thanks for starting this up.

Life gets faster every day

No time to think, no time to play

Hurry, chaos, lots of stress

Tension leads to sleeplessness

When will all this madness cease

Where is free time? Where is peace

I’m running, doing, till I drop

Give me buttons: Pause, Mute, STOP

Terrible event. I sympathize with the victims.

От этих ужасных вещей хочется далеко в космос, в другую галактику https://triberr.com/Another_Galaxy

The story you offer It allowed me to see many perspectives, it was very good.

rolling papers

Thanks, you have made a wonderful post. I love ang appreciate your commitment

Thank you very much and good luck

İstanbul hurdacı telefonu arayanlara en yakın istanbul hurdacı sitesi

Hurda alüminyum talaş, alüminyum kutu hurda, hurda alüminyum imalat artığı, alüminyum radyatör peteği, hurda alüminyum levha alımı yapmaya özen gösteriyoruz. Alüminyum jant, alüminyum çatı sacı, hurda alüminyum tas tabak, alüminyum tel, petek, hurda alüminyum fiyatları tencere tava İstanbul hurdacısıyız. İstanbul’da konumdan alüminyum klima radyatörü, hurda alüminyum curufu, alüminyum alikobant içi siyah, alüminyum eloksallı profil hurdası alabilmek için irtibat kurmanızı diliyoruz.

İstanbul’daki hadımköy hurdacı Firmalar arasındayız. Müşterilerimizin memnun olmasına öncelik vererek çok çalışmadan kazanarak hizmet vermeyi arzu ediyoruz. Bu neden ile her türde profesyonel hizmeti kapınıza getirmekteyiz. Bugün kü makalemizde sizin gibi hurda malzeme satmak isteyenlere İstanbul da hurda alanlarla firmamız arasındaki farkımızı anlatmaya çalışmaktayız. İstanbul da kalay, hurda üretim artığı, çelik hurdası, zamak hurdası, çinko hurdası almaya devam etmekteyiz.

Sizde her tür demir hurdası satışı yapmak için bizi kaydedebilirsiniz. Daha fazla çalışarak daha fazla kâr elde etmek istiyoruz. İstanbul çevresinde silivri hurdacı mı arıyordunuz? İstanbul daki en iyi hurdacı firmasıyla tanışma zamanınız gelmiş!

İstanbul da hurdacı firması olarak İstanbul’un tamamında her tür hurda alımı yapmaktayız. Her miktardaki atık malzemeleriniz için size en yakın yerde bulunan araçlarımızı yönlendirmeye devam ediyoruz. Otuz iki senelik deneyim ile piyasaya eşsiz yenilikler getirmekteyiz. En yakın İstanbul hurdacı ve arnavutköy hurdacı firması olarak hizmetinizdeyiz.

İstanbul Hurda Alan güngören hurdacı Firma Tonajlı hurda kurşun, hurda demir, hurda çinko, alüminyum hurda, bakır hurdası, kablo ve sarı alımı yaparken yükseltilmiş fiyat teklifleri veriyoruz.

İstanbul ortaköy hurdacı Telefonu Gördüğünüz gibi hurdacılık ve geri dönüşüm doğaya önem vermektir.

Şayet sizler de isterseniz hurda malzemelerin satışını gerçekleştirerek bize katkıda bulunabilirsiniz. Otuz iki senedir tonlarca hurdayı geri dönüşüm yöntemleriyle ekonomiye kazandırdık. Hizmetlerimiz ile çevreye daha çok zarar verilmemesi sağlandı. İstanbul güneşli hurdacı numarası sayfamızın içeriğinde bir tıkla arayabileceğiniz yerdedir.

İstanbul adresten her türde hurda alımı faaliyetlerimizi sürdürdüğümüz ilçeler arasındadır. Hemen arayarak, en yüksek hurda fiyatları ile hurdalarınızı nakit paraya döndürebilirsiniz. Bu yüzden hurda atık satmak nedeni ile hizmet numaramızı tuşlamanız yeterlidir.

Hurda bakır lama, kalaylı bakır tencere, TTR kırma granür bakır hurda, bakır tel hurda, kazan için özel fiyat teklifleri sunmaktayız. Hurda bakırlı petek, eşya, hurda bakır tepsi, hurda bakır levha, hurda bakır alımı, bakır hammadde hurdası satın alan yer arayanlara hizmetlerimizi vermekteyiz. Bakır hurda fiyatları içeriğimizde detaylı bilgi bulabilirsiniz. Sayfamızdaki hurda bakır fiyatları tüm İstanbul için geçerli olmayabilir.

Alüminyum hurda alanlar içerikli metne göz gezdirebilirsiniz Alüminyum piston hurdası, alüminyum araiş hurda, kartel, alüminyum profil hurdası, hurda alüminyum alımı, alüminyum matbaa kalıbı alan hurdacıyız.

Karışık kablo, iç tesisat kablo hurdası, antigron kablo hurdaları, enya kablo, tek damar kablo alıyoruz. Bu bölgede hurda yer altı enerji kablosu, fare yemez kablo, çelik içli kablo hurdası, çelik zırh kabloları alımı yaparken piyasanın üzerinde hurda kablo fiyatları sunuyoruz. İstanbul’da kablo hurda alan firmayız.

Paslanmaz krom alanlar içerisindeki İstanbul hurdacı firmasıyız. Dilediğiniz yerden krom paslanmaz 316 kalite hurda, krom 316 kalite hurda talaşı, krom 304 hurdası talaşı, hurda krom paslanmaz 310 talaşı, 310 krom paslanmaz hurda, 304 paslanmaz krom hurda alım satımı yapan İstanbul hurdacısıyız. İstanbul da hurda krom alıyoruz. İstanbul hurda krom fiyatları için arayabilirsiniz. İstanbul’da 201 paslanmaz krom hurdası talaşı, 430 paslanmaz krom hurda talaşı, krom 430 hurdası, krom 202 kalite hurdası, hurda krom imalat artığı, 201 krom hurdası, 202 kalite krom hurdası talaşı alıyoruz.

Yapılar için en önemli konu hiç kuşkusuz çatılardır. Çelik çatı uzun ömürlüdür. Hızlı kapatma açısından en ideali çelik satı tasarımlarıdır. Metal çatı, kenet çatı, panel çatı, skylight, hareketli cam çatı, polikarbon çatı, tonoz çatı benzeri çeşitleri vardır. Bütün bu çelik çatı projelerinin yıkım sökümü diğerinden değişik yapılmalıdır. Çelik konstrüksiyon bina prefabrike spor salonları sökülürken binanın inşa projeleri incelenmelidir. Böylece 2.el çelik çatı makası ve 2.el çelik konstrüksiyon malzemeler olarak satılabilecekler değerlendirilebilir. Çelik konstrüksiyon ve çrlik çatı sökümü yapıyoruz. Sökümden kalan çelikler geri dönüşüme kazandırılır. İstanbul’da çelik konstrüksiyon yapı söküm işlerinde deneyimli çalışanlarımızla güvenli hizmetler vermekteyiz.

weedonline

Thank you for sharing simple yet precise information in your blog site. Great job!

https://herbapproach.org/product-category/concentrates/vaporizer/

It’s beautiful worth sufficient on your blog site. I wanted to congratulate you on doing such an amazing blog. I appreciate all of your extra efforts. Excellent blog.

Kıbrıs gece hayatı katalog. Kıbrıs gece kulüpleri güncel bilgileri 2022.

Cannabis

Interesting blog! It provided us with valuable information. Keep up the good work!

Thanks for sharing this information.

Thanks for the information.

JBIT Institute dehradun , has remodeled their engineering programs on the philosophy of interdisciplinary learning. JBIT has opened up the doors for young minds who dare to dream.

I really like you You have knowledge that can be given to me.

I really like your take on the issue. I now have a clear idea on what this matter is all about.. UBANK789

Instagram Gizli Hesap Görme yollarını araştıran milyonlarca kullanıcı var.

Thank you very much for giving your good information I keep visiting your website constantly I like it Mumbai Call Girls |

Thanks, your article was really great.

I dug up some of your”posts” while I ‘thought, cogitated and cerebrated’ were extremely helpful, valuable, helpful, and useful.

I go to see each day some blogs and blogs to read content, but this webpage provides quality

based content.

The room is beautiful, I like decorating this room the way you share.

ROM download reference and mobile and computer training

Thank you for the great and informative post

I like to know more about this subject

please share more

뱃할맛이 나는곳 먹튀검증 안전한메이져

Thanks, your article was really me site https://limootop.com

nt88 webslot auto bet 2022 clik

nice blog post continue blogging.

nice post continue blogging.

nt88 เล่นสล็อตได้เงินง่าย แถม โบนัสเพียบมาลองเล่นที่นี้เท่านั้น

Follow the instructions from our website to successfully download and install Brother Printer Drivers to enhance the current features of the printer.

usually heavy monsoon rains have triggered floods that

Revolution Orsola de Castro and Carry Somers httsp://spita.ir set out to create a movement that would shed light on the fashion industry’s supply

I’m not that much of an internet reader to be honest but your sites is really nice, keep it up!I’ll go ahead and bookmark your site to come back later on.

reptiles for sale

FÜHRERSCHEIN ONLINE KAUFEN

Thanks For The Content..Really Good

More of Similar Content,Check The Link

Comprare Patente di Guida

These are some helpful forums for questions you may have. By entering discussions you can get additional advice and suggestions from others.

We are provide best service for youtube video downlod so you can copy your youtube video link and then paste your link in our website and take a best video quality MP4 and best quality for MP3 song.

Thanks For The Content..Really Good

آرایشگاه داماد

آرایشگاه داماد

آرایشگاه داماد

آرایشگاه داماد آرایشگاه داماد

آرایشگاه داماد

آرایشگاه داماد

آرایشگاه داماد حمید بخشی

خواب پدید آمدن صورتی است در حس مشترک، و علت پیدایش آن گاه اندیشه خود انسان است و گاه الهام عالم غیب، و تعبیر یا تأویل خواب آن است که معبر تشخیص دهد منشاء آن چیست، اگر از اندیشه خود بیننده برخاسته علت آن را به قرائن دریابد و تعبیر خواب اگر از عالم غیب است معنی را از صورت بیرون آورد چنانکه حضرت یوسف معنی فراخی و قحطی را از صورت گاو لاغر و فربه بیرون آورد.

باری خواب دریست که خداوند تعالی از عالم غیب بر مردمان عالم جسمانی گشوده و خواب صادق دلیل حسی بر وجود موجودات عاقلی است که از آینده جهان آگاهند و البته این موجودات عاقل هر چه باشند به هر نام نامیده شوند، ملائکه یا عقول یا انوار قاهره، اشرف از اجسام و موجودات مادی میباشند و انسان هم با آنها ارتباط و مناسبتی دارد

Your article is very useful

I have special thanks to the producer of this content

11 hydroxy metabolite

This is absolutely outstanding work.

BC Cannabis

Interesting blog site. Many things to learn. Good job!

Thank you and the post you provided, it was really interesting.

hi admin . The information given in this blog is very nice .

hi , I like it very much .

hi admin . It’s actually a nice and helpful piece of info.

hi,I really like your writing so much .

hi , very nice information .

Thank you and the post you provided, it was really interesting.

betflix gaming เข้าสู่ระบบโบนัส โปรสมาชิกใหม่

โบนัส ฝากเงินครั้งแรก

โบนัส กงล้อเสี่ยงโชค

โบนัส คืนยอดเสีย

A list of pretty cool games, make sure to check out the source to understand how they work. Before we start, we should mention the popular HTML5 game agario unblocked. is very addicting and funny to play with friends game.

after playing what is likely to be her final competitive

Rcg168 have fun and hunt for a lot of bounty Come สล็อตเว็บตรง

Jaopg เกมสล็อต แจ็คพอตแตกง่ายที่สุด เพลิดเพลิน ไปกับการรับกำไรอย่างมหาศาล หลักแสน สล็อตเว็บตรง

Pgslot-ogz เว็บเกมสล็อตออนไลน์ที่ดีที่สุดและมาแรงมากที่สุดในปี 2022 สล็อตpgเว็บตรง

Omega168 สล็อต เว็บใหญ่ อันดับ 1 พบกับผู้ให้บริการ เกมสล็อตที่มีการการันตี มากที่สุด สล็อตpgแตกง่าย

Thank you and the post you provided

I am fascinated by the article you write. like being trapped in a reverie it’s really good.

Informative post. I have never seen this type of article before keep sharing.

دانلود کتاب های pdf برای اجرا روی گوشی و لپ تاپ

Úžasný příběh, předpokládáme, že bychom mohli spojit pár nesouvisejících informací, přesto opravdu stojí za to hledat, kdokoli se dozvěděl o Středním východě, má také více problémů

https://casinositenet.com/

Gtos Terapi Yaptıranların Yorumları merak ediliyor. Sağlığınıza kavuşmak istiyorsanız mutlaka Gtos Terapi yaptırın.

Ya Fettah Mucizesi Yaşayanlar bu esmanın gücü ile kapalı kapılarınızı açın.

thanks for the information.

Comprare Patente di Guida

FÜHRERSCHEIN ONLINE KAUFEN

Thanks For The Content..Really Good

778 Eshot otobüs hareket saatleri, Özdere ve Ürkmez arasında geçtiği durak isimleri, 778 Eshot saatleri, güzergahı

Quando alguém escreve um artigo, ele / ela mantém o pensamento

de um usuário em sua mente é como um usuário pode entendê-lo.

É por isso que este artigo é ótimo. Obrigado!

https://www.safetotosite.pro/

Seyahat planlaması otoyol ücretleri dahil tüm masraflar önemlidir. Otoyol geçiş ücretleri ile ilgili detayları yazımızda bulabilirsiniz.

Thank you for your information. Go through our knowledge base articles to fix hp printer problems with the help of automated printer testing and fixing tools.

This is very educational content and written well for a change. It’s nice to see that some people still understand how to write a quality post.! สล็อตแตกง่าย

kaliteli bir blog sayfasi sizde bizi takip ederek en yeni oyunlar hakkinda yazilara ucretsiz olarak erisebilirsiniz.

Jumbo băng keo giá siêu tốt tại Bình Dương và TPHCM

The best troubleshooting guide to fix Brother printer offline on Windows 10 & Mac.

Brother printer wireless setup top guide from our updated document to fix the Isuue.

1001 oyunlara kolaylikla ulasim imkani sunmakta. Ust kisimdan dilediginiz oyunun on goruntusunu gorerek hoslanabileceginiz veya begenebileceginizi dusundugunuz oyuna tek tus ile erisebilirsiniz. Bilgisayariniza tahut mobik cihaziniza herhangi bir kurulum yapmadan web tarayiciniz uzerinden ucretsiz olarak 1001 oyun oynamaya baslayabilirsiniz. Ayrica bu kategori icerisinde online oyunlara da ulasarak sizin gibi gercek kullanicilarla birlikte oynayabileceginiz ,yani kiyasiya mucadele icerisinde bulunabileceginiz cevrimici oyunlarda mevcut. Bos vakitlerinizi degerlendirmrk istiyorsaniz veya caniniz sIkiliyorsan oynaxoyun size yetecektir. Ozenle sectigimiz oyunlari ucretsiz olarak telefonlarinizdan veya tabletlerinizden oynayarak eglenceli vakit gecirebilirsiniz.

Herkese merhaba, bu blogun gönderisini düzenli olarak güncellenmek için okumaya gerçekten hevesliyim. İyi şeyler içerir.

https://www.sportstoto.link/

ร่วมสนุกกันกับ เมก้า ของเรา mega game เข้ามาเล่นกันเยอะๆนะครับ

เมก้าเกม 65A collection of slot games, the more you play, the more you get rich, available 24 hours a day.

price mini pc in iran or mini computer beter than pc case iranminipc

minipc intel NUC intel price in Iran on the Iran minipc Store

قیمت کامپیوتر کوچک در ایران

Mini PC sales center in Iran – price of Intel mini PC – Asus mini PC – Mini PC MSE | IranMiniPC importer of mini PC, price of mini PC in Iran, features of mini PC: It is a small PC with high efficiency that offers all the features, specifications and capabilities of a normal PC computer with much less power consumption and small size. Gives. Mini PC sales in Iran – Mini PC online shopping

سالن آرایشگاه مردانه تهران بکس سالهاست که به عنوان یکی از بهترین آرایشگاه های مردانه تهران مشغول فعالیت بوده و سعی بر این دارد تا همواره هدف همیشگی خود یعنی بهترین ها را برای هموطنان و توریست های خارجی به ارمغان بیاورد تا نام ایرانی در این زمینه حداقل امتیاز و رتبه خوبی بگیرد..!

نوبتدهی و سیستم مدیریت مشتریان

از آپشن های مثبت سالن آرایشگاه تهران بکس محدود بودن تعداد آرایشگران و خلوتی و نوبتدهی سیستماتیک سالن میباشد.

برای اولین بار در ایران از سال ۲۰۱۵ در ایران شما میتوانید سیستم نوبت دهی و پیمنت خود را آنلاین و از طریق سایت انجام دهید.

Much impressed by this article.

Comprare Patente B

fuhrerschein-kaufen

Thanks for sharing.

Herkese merhaba, bu blogun gönderisini düzenli olarak güncellenmek için okumaya gerçekten hevesliyim. İyi şeyler içerir.

https://www.bacarasite.com/

The Inforinn is one of the greatest blog websites that provides updated and useful information for blog readers about digital marketing, business, technology, and fashion, among other topics.

mega gameล่าสุดThe website includes online slot games. That is a direct website, not through an agent Quality website

If you are looking for an online magazine to download new songs, movies, serials, and daily news, be sure to visit the SalamCool site

interested in participating in the event. I want to know the details. Like its specialty and features. So update those details in the site if possible so that I can attend it. Share more details on the site if possible https://www.theboatlink.com/search/boats-for-rent-toronto-on-canada

Business documents come up frequently in daily life, so by reading about them from an organizational development standpoint and learning how to apply those lessons to your own style, you’ll be better prepared.

Hi, I find reading this article a joy. It is extremely helpful and interesting and very much looking forward to reading more of your work.. สล็อตแตกง่าย

Ciao, mi fa piacere leggere tutti i tuoi post. Volevo scrivere un piccolo commento per supportarti.

https://www.sportstoto.link/

شیر ظرفشویی

you can get information about website design here

طراحی سایت | طراحی وب سایت

I really like your writing and arranging your speech. It’s very good.

Máy chế biến gỗ

Máy chế biến gỗ Bình Dương

https://binguma.vn Máy chế biến gỗ Bình Dương

Agree with u. I Love your web. i like your style writing and storytelling. I will review about that in my blogs Bonanza88 thank you.

Máy chế biến gỗ Binguma

สล็อตวอเลทฝากถอนไม่มีขั้นต่ำ สล็อตวอเลท เราคือผู้บริการรายใหญ่ เว็บตรงไม่ผ่านเอเย่นต์อันดับ 1 เข้าถึงง่าย ด้วยระบบ AUTO ทำรายการฝากถอน ที่ดีที่สุด เพียงแค่ไม่กี่วินาที ไม่ว่าจะยอดมากหรือยอดน้อย ขั้นต่ำเพียง 1บาทเท่านั้น ไม่ต้องมีบัญชีธนาคาร เพียงแค่มีแอพพลิเคชั่นทรูมันนี่วอเลท สมัครสมาชิกแล้วก็สามารถทำเงินได้ทันที สะดวกสบาย ใช้แค่มือถือเครื่องเดียว เกมส์สล็อตมากมายหลากหลายค่ายรอคุณอยู่ที่นี่

Glad to have come across this article. Thanks

ambbetwallet เกม slot ที่สามารถเข้าถึงได้ทันที แล้ว สามารถโอนเงินเข้าสู่ระบบเพื่อถอนออกง่ายมาก แค่รู้จักการใช้ true wallet แค่นั้นเลย

pgslot ยอดเยี่ยมเกมออนไลน์ สล็อตบนโทรศัพท์เคลื่อนที่ เป็บเว็บเกมออนไลน์ที่อยากจะแนะนำที่สุดต้อง pgslot-th.com เกมแบบใหม่ ไม่มีเบื่อ ไม่ซ้ำๆซากๆ ในแบบการเล่นเดิมๆอีกต่อไปๆ

بهترین گوشی های 2022 شیائومی

بهترین پردازنده موبایل

z8 slot เว็บไซต์เกมที่คนติดตามที่สุด พีจี สล็อต ได้คัดสรรค่ายเกมที่ได้รับความนิยมทั้งภาพ และ เสียง ความสนุกที่คุณไม่เคยเห็นจากเว็บไหนๆ เราเอาทั้งหมดมาไว้ที่นี้แล้ว อย่ารอช้า

เข้ามาสมัครเล่นเกม พนันออนไลน์ apollo pg เกมพนันออนไลน์ Apollo Slot Pg ที่สามารถช่วย ให้ผู้เล่นได้รับ ทั้งยังความเพลิดเพลิน ความระทึกใจ และก็โอกาศ ที่จะสร้างรายได้

Hello there, i follow your articles. Good sharing.

การทำงานร่วมกับผู้จัดทัวร์นาเมนต์และผู้พัฒนาเกม เช่น WePlay Esports, BLAST และ Riot Games รวมถึงผู้ดำเนินการเดิมพัน GRID สามารถระบุการแข่งขันที่มีการแก้ไขการจับคู่ที่อาจเกิดขึ้นได้ กีฬาอีสปอร์ต จากนั้นจะได้รับแจ้งเพื่อให้พาร์ทเนอร์สามารถตรวจสอบและดำเนินการตามความเหมาะสมได้ ทีมงานด้านความซื่อสัตย์ของ GRID ยังรักษาฐานข้อมูลความซื่อสัตย์ขนาดใหญ่ โดยการติดตามประสิทธิภาพของบัญชีรายชื่อ CSGO และผู้เล่นจากจุดยืนด้านความซื่อสัตย์ บริษัทสามารถช่วยแก้ไขปัญหาการจับคู่โดยรวบรวมจุดข้อมูลเหล่านี้

การเผชิญหน้าที่น่าตื่นเต้นอีกครั้งรออยู่ในรอบรองชนะเลิศ ซึ่งโรเบิร์ตสันจะพบกับมาร์ก วิลเลียมส์หรือมาร์ก อัลเลน ซึ่งจะเผชิญหน้ากันในช่วงเย็นที่วอเตอร์ฟรอนต์ ฮอลล์ โรเบิร์ตสันเริ่มบินได้ด้วยการพัก 73 ที่ทำให้เขาอยู่ในเส้นทางที่จะเข้าสู่เฟรมเปิด สนุกเกอร์สด แต่ Selby ไต่ระดับในวินาทีแม้ว่า Robertson จะพยายามอย่างกล้าหาญในการเล่นสนุ๊กเกอร์ก็ตาม โดยสองเฟรมแรกใช้เวลาเพียงไม่ถึงชั่วโมงกว่าจะเสร็จ

The content you create has always caught my attention. you are really good.

เครดิตฟรีไม่ต้องฝากก่อน สมัคร pg78

https://rmooosh.net/

https://www.ltobetlotto.vip/

It is the number one best search application.

https://xn--m3cdma8ae1a4c6a8l6e.com/

It is the number one best search application.

http://xn--82cd4anakh0e0gngc4c.com/

thank you

https://www.sagamingvip.casino/

aorLove

รูเล็ตเจ้ามือสด หากคุณต้องการประสบการณ์ ‘สด’ แต่อย่ารู้สึกอยากไปที่คาสิโนที่มีหน้าร้านจริง รูเล็ตเจ้ามือสดคือตัวเลือกที่ดีที่สุดของคุณ เกม เกมรูเล็ต นี้จะแสดงให้คุณเห็นฟุตเทจสดที่สตรีมโดยตรงจากโต๊ะรูเล็ตของจริง และให้คุณเดิมพันกับแอ็กชันที่เกิดขึ้นได้ บ่อยครั้ง คุณจะได้รับแจ้งว่าคุณกำลังดูคาสิโนสดใด และคุณจะสามารถสนทนากับเจ้ามือและผู้เล่นออนไลน์รายอื่นๆ ได้

Texas Slot สล็อตเว็บตรงในปัจจุบันนี้เกมสล็อตออนไลน์ได้รับความนิยมอย่างมากสล็อตเว็บตรงโดยเฉพาะการสมัครสมาชิกเว็บไซต์ เพราะว่าช่วยให้นักพนันทุกคนได้รับความสะดวกสบายในการวางเดิมพัน รวมถึงยังมีโบนัส และโปรโมชั่นเป็นจำนวนมากไม่ผ่านเอเย่นต์ไม่มีขั้นต่ำสำหรับใครที่กำลังมองหารูปแบบการวางเดิมพันสล็อตเว็บตรง 2023 และต้องการเอาชนะการวางเดิมพัน บทความนี้มีข้อมูลที่น่าสนใจ [ และเป็นประโยชน์กับคุณมากที่สุด

First, Thanks for this great information blogs. This post is very helpful to all users. Thanks a for sharing this awesome article.

In order for members to always get good value for money, such as free money credit, minimum deposit, important day bonuses, etc. สล็อตเว็บตรงไม่ผ่านเอเย่นต์ไม่มีขั้นต่ำ

I read a good article. It was a great help and got a lot of information. Please always share good articles and helpful information. I will share a lot of information on my website.https://mt-guide01.com/

But can you imagine the insane profits you could produce creating profitable video courses in niches that you’re not actually an expert in? Well, you can do just that with CourseReels.

Did you know that the e-learning and video-course industry is growing to be worth $325 BILLION by 2025? Ordinary people have made millions of dollars by selling courses on Udemy and got loads of free traffic to boot! There are 100s and 1000s of ordinary people just like you and me who are profiting and making big bucks merely by sharing their knowledge online.

If you sell anything, need customers or clients, then CourseReel can help you get results without spending months creating the video content yourself.

CourseReel helps you turn your free time into profitable video courses without complex planning, skill requirements, or video editing. All you need to do is upload an audio recording or copy-paste some text. Then CourseReel will turn that into video courses that you can finally start selling on Udemy, Coursera, or even on websites or funnels.

One of the trickiest pieces in transitioning to a proactive, data-led event strategy is knowing what data matters most and how to collect and analyze it efficiently.

We’ll go back to the basics and help you learn how to identify the KPIs most critical to achieving your event program goals and how to measure them effectively.

I just wanted to drop a quick note and say thank you for providing such quality content on your site.

First, Thanks for this great information blogs. This post is very helpful to all users. Thanks a for sharing this awesome article.

Yeah I totoally agree with your intention on who made my cloths dear.

I love this blog because it has so much good content that I always learn something new when I visit. It is easy to read and well organized, which makes it a lot easier for me to find what I am looking for.

The blog has been a great resource for me as I am writing my dissertation. It is so easy to use and the information is reliable.

saya suka dengan blog ini dam informasi dapat diandalkan

Very good blog.Much thanks again. Cool.

Maintaining your home privacy is very important after all your home is your kingdom, instead of ignoring the prying eyes of people outside your house, why not shut your curtains by just pressing a button. Motorized Curtains Dubai are the best solution to maintain your privacy and avoid light to enter your room. By touching a button on the remote control or even through your mobile phone, you open or close your curtains.

Motorized Curtains in dubai

Black pug puppies for sale

Great content. Keep it up

Thank you for sharing this content. We appreciate your efforts and hope that others will find it helpful.

Thank you for sharing this useful information, I will regularly follow your blog. Excellent post!

JPCASH is the most complete online gambling site that provides recommendations for gacor games and offers the best real money games in 2021

First, Thanks for this great information blogs. This post is very helpful to all users. Thanks a for sharing this awesome article.

همه چیز درباره دیسک ترمز

Financial management is a constant struggle between spending, saving and investingg2grich888 Money is essential for running a household or a business. Every country uses money to buy goods and services- and to pay their employees. Therefore, managing money is essential for running an organization successfully. Understanding how to manage money is essential for everyone.

sorunsuz olarak oynayabileceginiz atari oyunlari hem telefondan hem de tabletten calismaktadir.

Every country uses money to buy goods and services- and to pay their employees. Therefore, managing money is essential for running an organization successfully.

Financial management is a constant struggle between spending, saving and investingg2grich888 Money is essential for running a household or a business. Every country uses money to buy goods and services- and to pay their employees. Therefore, managing money is essential for running an organization successfully. Understanding how to manage money is essential for everyone.

https://asemoo.com/christmas-tie-and-shirt/

CHRISTMAS TIE AND SHIRT :A PERFECT GUIDE FOR MATCHING AND COMBINATIONS

nice bLog! its interesting. thank you for sharing…. สล็อตแตกง่าย

Interesting topic for a blog. I have been searching the Internet for fun and came upon your website. Fabulous post. Thanks a ton for sharing your knowledge! It is great to see that some people still put in an effort into managing their websites. I’ll be sure to check back again real soon. UBANK789

Article. I like it. The creator of this post clarifies never-endingly yahoo mail sign up strong concentrate no plans. Thankful for posting.

Thank you for sharing this useful information, I will regularly follow your blog. Excellent post!

The content is great here, and I have found a lot of interesting things to read.

I just wanted to drop a quick note and say thank you for providing such quality content on your site.

Today I am very happy to hear from you.Nothing is really impossible for you. your article is very good.

Download Exclusive Music By : « Shervin – Bahar Oomad » With Best Quality , Direct Links And Lyrics In MusicTarin

The entrance to the game to play must be told first that it will be a way to search for the name of the website, whether it is the 168Galaxy website, it is a popular website and has the form of a game to try. Given to everyone to try various slotxo games, and of course, in all 3 of these websites, there are famous camps like slot slotxo that when you play, you will receive a jackpot prize. Not missing a hand at all.

Hi

This is really very usable content honorable admin sir https://cutt.ly/PMlqGKe

J’aimerais vous remercier des efforts que vous avez déployés pour rédiger cet article intéressant et bien informé.

https://majorsite.info

We also want to read your articles on a regular basis.

Saya ingin mengatakan bahwa artikel ini menakjubkan, tulisan yang bagus dan datang dengan hampir semua info penting. Saya ingin melihat lebih banyak posting seperti ini

https://majorsite.one

I’ve been waited for so long

Hi there all, here every person is sharing such know-how, so it’s fastidious to read this

blog, and I used to pay a visit this web site everyday.

I can’t stop playing Flappy Bird. It makes me happy. Thanks for this great game.

jdb aw ใครที่มองหาเกมดีๆสนุกๆ ลองมาเล่นเกมออนไลน์ดูนะคะ เล่นผ่าน มือถือง่ายมาก แนะนำเลยค่ะ ระบบดี ฝาก-ถอน ไม่มีขั้นต่ำ แถมระบบออโต้อีกด้วย เฉพาะแก่นักพนันออนไลน์เลยนะคะ เรามีคำแนะนำให้และวิธีการเล่นฟรี

Do you need to make some quick changes to a PDF, but don’t have the software to do so? A1office online edit pdf is here to help! With our simple and easy-to-use editing tools, you can make all the changes you need in no time. Plus, our website is completely free to use! online pdf editor

varvip999 จีคลับ 2022 ระบบฝาก-ถอน ปลอดภัย รวดเร็วที่สุด

The content is great here, and I have found a lot of interesting things to read.

بهترین گوشی های اندرویدی:

https://gholab.ir/blog/%D8%A8%D9%87%D8%AA%D8%B1%DB%8C%D9%86-%DA%AF%D9%88%D8%B4%DB%8C-%D9%87%D8%A7%DB%8C-%D8%A7%D9%86%D8%AF%D8%B1%D9%88%DB%8C%D8%AF%DB%8C-2022/%D8%AF%DB%8C%D8%AC%DB%8C%D8%AA%D8%A7%D9%84/%D9%85%D9%88%D8%A8%D8%A7%DB%8C%D9%84

انواع گوشی موبایل

Astonishing! It’s a big deal for me to cover the new and true point work you have referenced in this web blog. Mercifully share something else for the adherents.

First, Thanks for this great information blogs. This post is very helpful to all users. Thanks a for sharing this awesome article.A Nasha mukti kendra is a place where people with physical or mental disabilities can go to receive help.

The content is great here, and I have found a lot of interesting things to read.A Nasha mukti kendra is a place where people with physical or mental disabilities can go to receive help. The staff at the centre will work with the individual to help them regain their independence.They will provide therapy, support, and guidance to help the individual reach their goals

Much obliged to you for sharing such an astonishing recipe. I’d very much want to peruse some more and get to test them. Keep up the extraordinary work.

I am Korean. I agree with this article. I think our country needs a lot of professional people like this. Sharing and sharing opinions with each other is a good thing anywhere in the world. Thank you for the good words. I learned a lot from your writing!메이저사이트

Lottery 12 Zodiac ltobet

Relevant!! Finally, I have found something that helped me. Cheers!

ใครที่ต้องการเล่นเว็บยอดนิยม2022ครั้งแรกได้ง่ายๆเพียงเลือกเว็บไซต์ของเราแล้ววมัครสมัครสมาชิกซึ่งตอบโจทย์นักเดิมพันที่ต้องการวางเดิมพัน pg กำลังได้รับความนิยมมากที่สุดในปี2022แล้วคุณก็จะได้รับสิทธิพิเศษต่างๆหลีงได้สมัคราเข้าร่วมเป็นสมาชิกกับทางเรารับรองว่าจะได้พบกับความบันเทิงและผลตอบแทนภายในเกมที่คุ้มค้า

The content is great here, and I have found a lot of interesting things to read.