PAGE NAVIGATION

Introduction

Occupy Wall Street made inequality visible. The top 1% were challenged for the disproportionate allocation of power in the form of capital, political influence, and control of the means of production.[1] Those engaged were fighting for equality. The lack of income and wealth equality resonated globally. The movement was in part inspired by Arab Spring movement in the United States to battle wealth and income inequality against the elite. Occupy Wall Street and Arab Spring shared the two fundamental drivers: a deep sense of injustice and inequality.[2] As with many other global social movements, social media served as a catalyst to organize and unite the movement’s supporters. Social media functioned as a medium by which the slogan, “We are the 99%” originated, changing the political and social discourse of wealth distribution. Although this discourse highlights a greater portion of society’s wealth disparities, the Occupy Wall Street movement did not solve all problems related to inequality. The efforts made by the Occupy movement did illuminate issues of inequality to set the stage for future movements to create greater change.

Key Images

The characteristics of Occupy Wall Street—including the focus on occupation, lack of clear leadership, and extent of the movement—resulted in the production of a number of key images to represent the movement.[3] Occupy Wall Street utilized social media including Twitter, Tumblr, Facebook, and Reddit to spread memes and images.[4] Much of the substance that circulated the internet with significant following involved images from protests of occupants and the police force. Picketing was often depicted in the images of the protests with signs containing a large spread of messages with anti-capitalism as a commonality.[5]

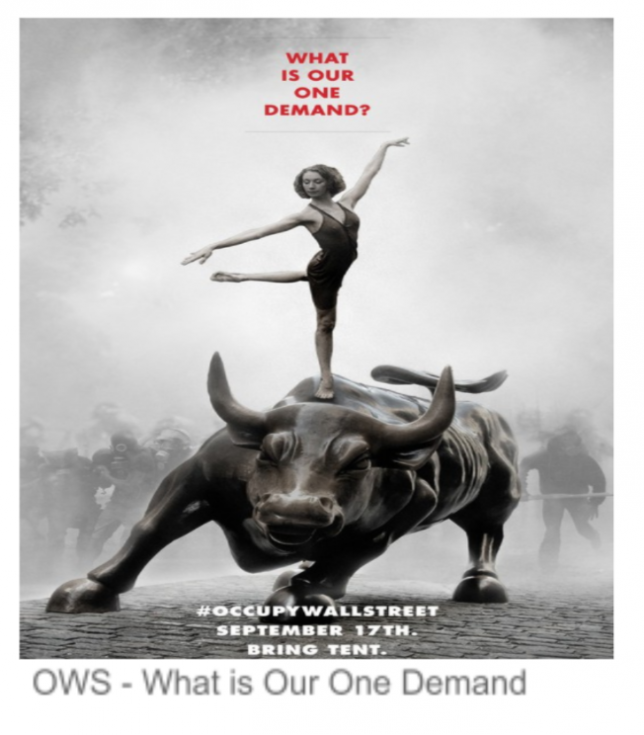

The Wall Street Bull statue known as Charging Bull was a repeat subject of the Occupy Wall Street propaganda.[6] The reason the Charging Bull was used as the subject frequently is because it represents the aggressive financial optimism and prosperity consistent with common views of Wall Street.[7] Illustrations incorporated chains and ropes taming the bull. One of the most common figures is the ballerina dancing on top of the Wall Street Bull. The ballerina acts as a symbol of defiance against the Bull. She represents the light of the 99% outside of Wall Street.[8] During the initial protests on September 17th, 2011, police barricaded the bull as protection[9]. This sent a message that sparked controversy. Police officers patrolled the figure acting as though protesters were going to vandalize and damage the statue. The chairman of the Bowling Green Association, Arthur Piccolo, expressed “If the police feel they need- which is open to question- to protect this plaza, they should do it the same way they protect other locations in the city, with less obnoxious methods”.[10] As a result, the charging bull became a star among the movement. One key photo of Occupy Wall Street features a ballerina atop of the Charging Bull with the caption, “WHAT IS OUR DEMAND?”.[11][12] The poster was published in Adbusters.[13] The poster and its origin was crucial in launching the movement and achieving the movement’s hashtag. Co-founder of Adbusters, Kalle Lasn, said regarding the poster,“I felt like this ballerina stood for this deep demand that would change the world. There was some magic about it.”[14] Other popular themes include memes reflecting police brutality, corporate popular culture, and images from protests with captions.”

Another figure of resistance against Wall Street,“The Fearless Girl,”[15] is a statue that was placed in front of the Charging Bull as a response to the gender pay gap and the lack of women on corporate boards.[16] It is important to note that this statue was installed on March 17, 2017, well after the Occupy Movement. The confident, defiant girl faces the bull directly. The scene is a visual commentary against the corporate power that was a result of Occupy Wall Street’s changing political and social discourse.

Context

Occupy Wall Street started as a protest in New York City’s Zuccotti Park on September 17th, 2011. The movement highlighted public issues supporters of the movement believed were created by the Wall Street financial district such as income inequality, wealth distribution, and their belief of an unfair global economy.[17] The movement’s central concern was that the top 1% was causing and reinstating income inequality as “unregulated financial capitalism crashed the global economy and caused immiseration of millions”.[18] Thus, the supporters of the movement represent the remaining population outside of the top 1%: the 99%. They argued that corporations and banks had too much power over the vast majority of people.

Wall Street’s influence was the central target of their attack.[19] The economic and political power held by Wall Street’s elite is disproportionate to the rest of the population. The issues expanded beyond New York City. The greed and corruption of the corporate world was emphasized by protesters and supporters of the movement through methods such as occupation, picketing, demonstrations, internet activism, and meetings of direct democracy to highlight civil disobedience.[20] Occupy Wall Street used consensus-based decision making instead of introducing a spearhead to lead the movement. In a way, this supported the impact of the people and allowed for increased participation against institutions and authorities. Protesters occupied corporate headquarters, board rooms, foreclosed homes, and banks. The movement inspired action and participation against the out of control corporate world that they believed was inhibiting their lives by restricting their own success and wealth.[21] Their focus as the 99% built an inclusionary environment of participation.

The movement lacked formal leadership position. Instead, the movement functioned as an assembly where consensus decision making was required.[22] They used a form of direct democracy in which anyone could participate and speak at meetings. Meetings were opened to all and speakers could add themselves to a queue that acted as a line up. This prevented a rise of corporate power within the movement. The movement spiked in momentum and popularity once incidents of police brutality emerged.

Timeline

July 2011

First Planned Protest. Adbusters proposes a peaceful demonstration to Occupy Wall Street.

August 2011

Anonymous Supports OWS. The hacktivist group Anonymous encourages its supporters to take part in the protest.

September 2011

First OWS Gathering/Protest. The first OWS protest, consisting of around 1000, people takes place at Zuccotti Park.

September 2011

Police Arrests Begin. The NYPD arrests around 80 protesters, and claims of police brutality are raised.

September 2011

Anonymous Releases Data of Police Officer. Personal information about a police officer who maced a woman, is released by Anonymous.

October 2011

Brooklyn Bridge Protests. Protesters marched across the Brooklyn Bridge, until the police started arresting hordes of people.

October 2011

Foley Square to Zuccotti Park March. Around 5,000-15,000 protesters peacefully marched to Zuccotti Park; 200 arrests were eventually made[23]

October 2011

Obama Supports OWS. President Obama issues a statement in support of the Occupy Movement.

November 2011

Police Clear Zuccotti Park. At 1am, police unexpectedly clear Zuccotti Park, the timing of which becomes extremely controversial. This effectively ends/silences the movement.

December 2011

3-Month Reoccupation. Protesters call for a reoccupation of Wall Street on the movement’s 3-month anniversary.

March 2012

6-Month Anniversary. A reoccupation of Zuccotti Park is attempted – over 100 arrests were made[24]

September 2012

1-Year Anniversary. Thousands protest in the financial district, to celebrate the Movement’s one-year anniversary.

September 2012 – Present

Yearly Anniversary Protests. Yearly anniversary protests have occurred, with a notable one occurring in 2015.

On July 13, Occupy Wall Street was born when Kalle Lasn from Adbusters, an anti-consumerist organization, made the proposal for a peaceful demonstration to occupy Wall Street to bring to light the disproportions of wealth inequality. On August 23, the hacktivist group Anonymous encouraged its followers to take part in the protest. On September 17, the first Occupy Wall Street protest took place in Zuccotti Park. It was chosen as the protest location because police found out about the protests beforehand through organizers and media outlets, and fenced off One Chase Manhattan Plaza and Bowling Green Park, which were the first and second choices for the protest, respectively. On October 1, a protest was planned on the Brooklyn Bridge. This protest was controversial in that more than 700 arrests were made. A few days later, on October 5, the movement grew to its largest, as an estimated 15,000 individuals marched from Foley Square to Zuccotti Park. It was also around this time that many smaller protests in other cities and college campuses sprung up. On October 15, global protests occurred all around the world. Roughly 900 cities participated, including cities such as Sydney, Hong Kong, Tokyo, Paris, Madrid, and Sao Paulo. The movement became more controversial on November 15, when around 1am, the NYPD began clearing Zuccotti Park. A statement was released by Mayor Bloomberg’s office explaining that the action was taken due to the safety and fire hazards that the protest was creating in the location. However, it was argued that the action took place at this time to avoid press coverage, as even a CBS press helicopter was not allowed into the airspace above the park.The length of the life of the Occupy Movement is debatable in that many major events happened quickly within the span of a few months. Smaller events continued for years after, and some occupy-inspired events still occur today in 2017. This timeline is representative of the major events that occurred during the movement.

While this was not the end of the movement, it was one of the last major events. Protests continued to happen after this date in New York and in locations around the world, but the movement began slowing down. Some notable protests that occurred after this date occured in intervals, such as the three-month anniversary, the six-month anniversary, and the one-year anniversary protests. Demonstrations have continued to occur on every yearly anniversary of Occupy Wall Street, with a major one occurring in 2016, during the occupation’s five-year anniversary.

Active Dates

While the end date of the movement is debatable, the origin of the movement can be traced to June and July of 2011, having emerged due to Kalle Lasn and Adbusters. The movement can be classified as having ended, but occupy-inspired events still continue to occur. In addition, because the movement strived to advocate for certain ideologies and to create a larger conversation around particular issues, it can be argued that it still lives on today, as problems such as income inequality and corporate influence on politics are yet to be solved.

Demographics

Although the movement strived to embody diversity and advocate for marginalized individuals, the demographics recorded indicate a sharp skew towards a particular profile. For example, according to a survey of people that visited OccupyWallSt.org, 64% were under the age of 35, 20% were over the age of 45.[25] The protesters were also reported to generally be younger earlier on, with the number of older individuals growing as the movement caught further momentum. This same survey on OccupyWallstret.org also captured racial demographics and found that the protestors were 81.2% White, 6.8% Hispanic, 2.8% Asian, 1.6% Black, and 7.6% other. This lack of racial diversity proved controversial in that it was argued that the movement was not representative of the racial demographics of America or the 99%. This lack of racial diversity can be attributed to the fact that Occupy had no formal leadership. As a result, the movement saw the emergence of charismatic white men taking on activism roles.

Furthermore, a study by sociologists at the City University of New York found that over a third of the protestors had incomes over $100,000, and that more than two-thirds had professional jobs[26]. On the other hand, these researchers also found that that nearly a third of the protesters had been laid off or lost a job, and that a similar number said they had more than $1,000 in credit card or student loan debt. The majority of protesters did not fall within income levels most representative of the movement, but they did cover a very large spectrum. A number of explanations emerged attempting to explain why this was the case. Such explanations ranged from a lack of mobilization efforts targeting low-income individuals, to the message simply not resonating with the entire 99%[27][28].

The education levels of the protesters were also identified in this study, and it was found that 76% of the protestors had bachelor’s degrees and that 39% had graduate degrees. These statistics challenged the credibility of the movement and its message, in that upper-class, educated males were disproportionately represented during the protests.

Furthermore, a survey by a Fordham University political science professor was used to determine the political affiliations of the protestors. This survey found that 25% of the people were Democratic, 2% Republican, 11% Socialist, 11% Green Party, 0% Tea Party, 12% other, and 39% of the respondents said they did not identify with any political party. This survey, while often cited to represent the political affiliations of the protesters, may not be the most accurate or representative due to the small sample size of 301 people. Nonetheless, the movement was still empirically less diverse than would have been desired.

Allies and Partner Organizations

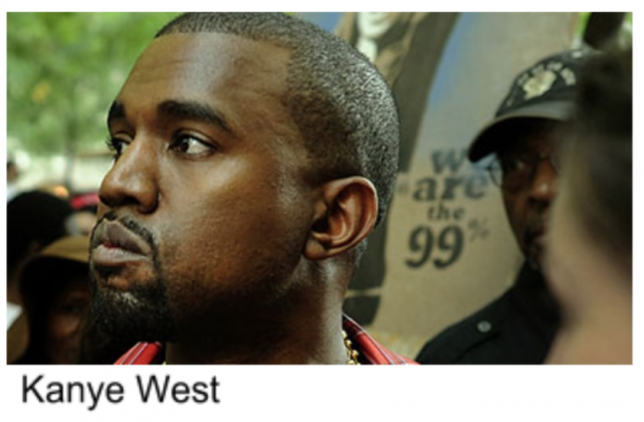

A host of allies emerged during the Occupy Movement. Several labor groups and unions pledged their support for Occupy demonstrators, and some even actively took part in Occupy protests. These groups and unions included groups such as the Transport Workers Union of America, the United Auto Workers, and the AFL-CIO. These groups contributed to Occupy by raising awareness amongst their members, and by giving the cause added credibility. In addition, a number of celebrities and notable individuals openly voiced their support for the movement, such as Jesse Jackson[29], Kanye West[30], and even the Vatican[31]. Furthermore, just as the protester demographics included wealthy individuals, many wealthy businessmen and even financiers openly voiced their support of the Occupy Movement, such as Warren Buffett, George Soros, and then Citigroup CEO, Vikram Pandit.

While the diverse support was helpful in raising awareness and creating a mass of followers, it also raised confusion because the movement’s slogan was “We are the 99%.” This slogan was not as representative of the movement as wealthier individuals began voicing their support.

Social Media Presence

Platforms and Hashtags of Occupy Wall Street

The question about whether social movements should expand through usage of preexisting social media platforms or rather create a website of their own is one that our Social Movements and Social Media class has examined in depth. Collectively, we came to the conclusion that there is no correct way to spread the word about a particular movement. Although, we also realized that the social movements that have been the most successful in going viral and circulating worldwide have utilized every available media outlet to their disposal.

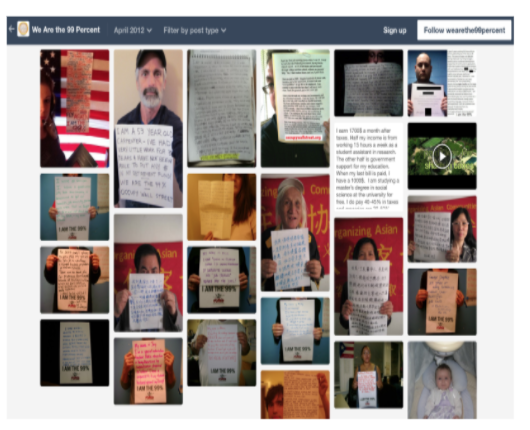

The Occupy Wall Street movement adopted the slogan “We are the 99%,” which came from a Tumblr page[32] with that very title. Two media activists, Priscilla Grim and Chris (last name unknown), created this page with the intent of identifying individuals that made up the 99% and creating an outlet where they can share their stories and read about others who stood alongside them.[33] The page launched in August of 2011 as a social media outlet that allowed individuals to easily share their stories. When asked how they can claim to speak for 99% of people, the page responded, “We do not claim to speak for anyone, we just present stories.”[34] Users would write a paragraph to summarize their story on a piece of paper detailing the relationship between them and the 99%. The site is no longer fully functioning. The last post was from October of 2013. The Tumblr page was crucial in spreading the message of Occupy to start a global conversation about income and wealth inequality.

Occupy Wall Street received considerable media attention in September of 2011 after a video showing a group of nonviolent female protesters being pepper-sprayed went viral and was later broadcasted on TV networks.[35] After Occupy Wall Street gained popularity, the hashtags surrounding the movement could be found on every media outlet available; some of the more popular hashtags include #OccupyWallStreet, #OccupyWallSt, #Occupy, and #OCW.

A team within the movement known as the Occupy Research Network worked alongside datacenter.org to produce the ORGS, an online survey that incorporates responses from 5,000 individuals to questions about the types of media they used to either gather information or spread the word about the Occupy Wall Street movement. Their feedback is a great depiction of just how many platforms the movement spanned across. With regard to preexisting social media platforms, 64% of people said they used Facebook, 23% used Twitter, 24% chose to blog, and 29% used YouTube for either creating or watching videos. 43% of respondents said they engaged in face-to-face interactions where they spoke about the movement directly with other individuals, whether it be at a march specific to the social movement or just conversing with someone in their day-to-day life. Traditional news outlets also played a huge role in covering the Occupy Wall Street movement seeing as that 24% of people said they read about it in a newspaper, 17% said they watched reports on the television, and 17% heard about it on the radio. 19% said they followed the 24-hour live-stream that was broadcasted through GlobalRevolution.tv, which reported to have around 8,000 viewers per day in 2011. Lastly, a whopping 84% of respondents said they used websites or emails that were intentionally created to cover the movement. The results that come up from running a Google search on “Occupy Wall Street” include its Wikipedia page, a few official websites, and various articles from sources such as CNN, The New York Times, and The Wall Street Journal.

In addition, there were a number of non-traditional outlets that individuals utilized during the movement. One of the most prominent was Indymedia. According to their website, “Indymedia is a collective of independent media organizations and hundreds of journalists offering grassroots, non-corporate coverage. Indymedia is a democratic media outlet for the creation of radical, accurate, and passionate tellings of truth.” This website, which still exists today, served as a place where individuals could give reports on the events and happenings during the Occupy protests. Another website, occupywallst.org, which also exists today, represents a good example of the open forums where people discussed their thoughts and coordinated events. Overall, while there were a number of ways to participate in the movement, they weren’t able to sustain engagement, as the Occupy Movement quickly faded.

Organic vs Planned Growth

There wasn’t much planned growth in the Occupy Movement, as the movement was leaderless and horizontal. The only “planned” aspect of the movement was Adbusters encouraging people to occupy Wall Street in protest.

The movement gained momentum largely due to the police brutality and violence against protesters. After the initial protests in Zuccotti Park, the movement gained significant following when a video surfaced and spread through the media from activism on September 24th, 2011. The video featured a New York Police Department Deputy Inspector spraying a young group of unarmed females with pepper spray. Additional alleged cases of police brutality brought increased levels of attention to the movement with a call for assistance and action for human rights. Arrests in general motivated media coverage, which helped the movement grow by spreading its message on news outlets. The lack of planned growth proved highly detrimental in that the movement quickly faded after a few months.

Analog Antecedents

As mentioned, the Occupy Movement was inspired by the Arab Spring Revolution. Seeing the political charge of the Egyptian youth inspired occupiers as the movement took off. In fact, this connection was explicitly lauded on the OWS website with the statement, “We are using the revolutionary Arab Spring tactic to achieve our ends and encourage the use of nonviolence to maximize the safety of all participants[36].” Furthermore, both movements represent an underlying sense of injustice and invisibility[37].

Neither Arab Spring nor Occupy compiled a formal list of demands, but both movements vocalized a host of grievances. While the two movements may not be directly comparable, Arab spring set the stage for Occupy to occur.

Impact of Occupy Wall Street

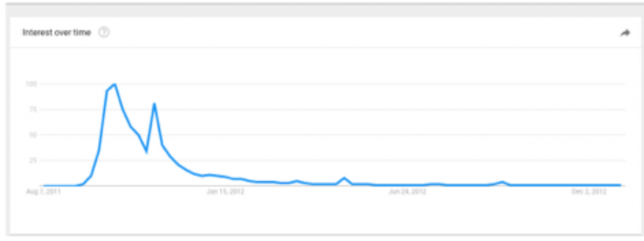

Although Occupy Wall Street pages still exist on Facebook and Twitter and videos are still posted on YouTube, the movement has been largely inactive for some time now. Websites that were previously used when the movement’s popularity was peaking such as http://occupytogether.org/ are no longer active. The URL now directs the viewer to a page that says Occupy Together “was an independent group of activists,” but that the site is “not currently being maintained.” There no longer exist Facebook invites[38], like the one displayed, to events that are organized to spread the word about the Occupy movement. The Google Trends chart[39] shows the number of times that the topic “Occupy Wall Street” was typed into Google between September of 2011, when the movement was at its peak, and December of 2012. What lasting impacts did #OccupyWallStreet have? Sadly, the way Wall Street functions today is almost identical to how it ran seven years ago before this movement began.

Although there have been hardly any major shifts to the overall culture on Wall Street, a few of the messages that the Occupy Wall Street protesters were trying to get across did manage to become a part of ongoing conversations around the world. The growing increase on income inequality not only within the United States but all around the world is more notable and recognized than ever before. The distinctions between the 1% and the 99% are real and thanks to the Occupy Wall Street movement, this contrast is being brought up not only in everyday conversation, but also in political and economical discussions. In fact, this can be evidenced by Obama’s state of the union address in 2012.

Given the Occupy Movement’s emergence in late 2011, and the notability it quickly earned across the nation, it was able to earn some mention during the event. In the speech, President Obama openly acknowledged the presence, and widening of income inequality. He called economic fairness “the defining issue of our time.” He also made statements such as, “Folks at the top saw their incomes rise like never before, but most hard working Americans struggled with costs that were growing, paychecks that weren’t, and personal debt that kept piling up.[40]” It is evident that Obama is addressing the salient point of the Occupy Movement, and his speech included further populist tones as spoke about the wealthiest Americans needing to pay their fair share of taxes. His speech is an example of how Occupy Wall Street was able to start a conversation in politics, especially as it relates to addressing income and economic inequality. Obama’s state of the Union Address serves as an example of how these topics eventually became integrated into political conversation.

Unfortunately, the effect of this discourse was short lived seeing as that the Occupy Wall Street Movement did little to influence change during the 2016 election. Occupy Wall Street advocates put their faith in Bernie Sanders because he put an emphasis on spotlighting income inequality and the issues of wealth distribution within the country. They encouraged citizens to vote for Sanders, but just as the movement itself failed to bring along any major changes, Bernie Sanders also failed at winning the popular vote in the 2016 election. Lastly, large institutions and corporations within Wall Street made no attempts to make changes in response to the Occupy Wall Street movement; the hiring process for companies such as investment banks and consulting firms didn’t change and salaries for their employees also remained the same. Then again, it is hard to implement changes in accordance to what the people want when the people do not even know what they want!

Occupy Wall Street vs. The Tea Party Movement

Most social movements that start online are extremely popular and grow at incredibly fast rates by capturing people’s attention in an instant. Similar to Occupy Wall Street activists, the Tea Party Movement, which arose in 2007, utilized social media as a tool to grow the movement and expand their reach to a larger audience. We can compare the rise and fall of both the Tea Party Movement and the Occupy Wall Street Movement to corroborate the idea that media attention is directly correlated to actual activist activity.

Every movement starts with a message. Tea Partiers advocated for liberty; they came together shortly after the Affordable Care Act was passed by President Obama because they believe that local communities and governments should be in charge of major decision making rather than having executive laws placed by federal governments[41]. The growth of the Tea Party movement was very organic and more people joined as the group’s online presence grew. They were supported by news broadcasters such as FOX News (which tends to report news with heavy right wing ideals), which helped spark popularity in the movement as well. Their mission was to raise money in order to back the kinds of candidates they deemed fit. While they succeed in boosting capital through online fundraising platforms, their resources were quickly depleted due to extremely persistent republican campaigns.[42] Tea Partiers eventually split up during the 2016 election in support of either Ted Cruz or Donald Trump, which further weakened the movement by ruining their united front. The Tea Party movement experienced a naturally inclining growth, but its demise was by no means organic. Nowadays, the Tea Party movement is rarely referenced and whatever is left of it is controlled and censored by President Trump.[43]

Occupy Wall Street was entirely different in nature. Its message was a cry for equality. Activists were sick of being complacent about the 1% having full control over corporations, politics, and the economy. The rise of the movement was completed planned out. As previously mentioned, event pages were created on social media for the September 17, 2011 gathering in Zuccotti Park which jump started the movement and their online presence. Similar to the Tea Party Movement, Occupy Wall Street was endorsed by news stations, newspapers, and magazines and grew in size due to increased popularity.[44] Slowly, Occupy Wall Street began to get less and less media attention until eventually the movement dismantled all together. As opposed to the Tea Party Movement, Occupy Wall Street had an abrupt start and an organic end. The traces and remains of both movements can still be found on social media and movement specific websites today, but they are by no means active in the way they were back in 2010 and 2011.

International Significance of Occupy Wall Street

While this people-powered movement had active mobilizations in almost every major U.S. city, including Oakland, Los Angeles, Boston, Seattle, and Chicago, Occupy Wall Street was also very popular beyond the confines of the U.S. United States. Support for the movement spread quickly and within the first six months of the Zuccotti Park demonstrations, over 6500 protesters had been arrested in over 1000 cities both nationally and internationally.[45] The issues being addressed were relevant and applicable across international lines as they associated their goals with the majority of people and is considered an “international mobilization of the indignant.”[46] The idea that America was exclusively in trouble and needs rebuilding is wrong. Occupy member explains, “Imperialism is built on the back of these third world workers and affected by the same conditions”.[47] United States corporate success has impacts across the globe. Social media played a crucial role in the spread of Occupy Wall Street’s message.

One of the many Occupy Wall Street websites[48] used throughout the movements lifetime states that “We are using the revolutionary Arab Spring tactic to achieve our ends and encourage the use of nonviolence to maximize the safety of all other participants.”[49] Challenges of power in countries that have greater amounts of suppression were studied as models to implement and apply to the Occupy Wall Street Movement.[50] Although the protests in the Middle East were unsuccessful in maintaining a nonviolent movement, the Occupy Wall Street movement was carried out in a relatively non-violent manner thanks to social media platforms which allowed for conversation rather than violence.

Critiques of Occupy Wall Street

So why is it that the Occupy Wall Street Movement allegedly failed? Some may argue it is due to the lack of define leadership or hierarchy within the movement. The movement’s growth was natural and it spread like wildfire, leaving no time to assign definite leaders to spearhead the motion. The second major critique of the Occupy Wall Street movement is that it lacked a clear agenda or list of demands that went beyond acknowledgment and inclusion. While there is income inequality and there exists a clear disconnect between the wealthiest 1% and the remained 99% of the population, the problem was that the movement did not propose a solution. Building on this, there was also a disconnect between the Occupy Wall Street movement participants and outsiders. To some people, the argument became one of rich versus poor. They believed protesters were after equality for all when all that needed to be changed was the incredible amount of power that major corporations within Wall Street had (and still have) over the world economy. People wanted to believe that upward mobility was possible with the help of proper government regulation. The third issue that arose for protestors was that they were targeting the wrong audience. The movement targeted the financial industry and institutions such as banks, hedge funds, and brokerage firms when perhaps they should have been going after politicians in Washington for not taking measures before the financial crash of 2008. At the same time, the movement blamed all of Wall Street when in reality, not every person who worked at a financial institution played a role in the financial crisis. The final flaw of the Occupy Wall Street movement is the fact that they called themselves “the 99%” when the scope of their movement does not cover everyone who is part of the 99%. Most activists were white, middle-class individuals. There was a lack of representation from people of color, women, and members of the LGBTQ community. The real 99% encompasses everyone, but the movement itself failed to do so.

Conclusion

Occupy Wall Street serves as a unique social movement, in that its origins can be traced to an Adbusters post in the summer of 2011. The movement addressed rising income inequality, a poignant issue following the 2008-2009 financial crisis. Although the movement was very short-lived, it was able to quickly reach global prominence, as evidenced by the Occupy protests that occurred all over the world.

While its lasting impacts have been debated and often criticized, evidence suggests that it was crucial in bringing the term “income inequality” into America’s political vernacular. Thus while the movement, during its phase of peak notability, did not achieve tangible goals, we continue to see its lasting effects in our contemporary political conversations.

Team Member Bios

Olivia Hauger

I am a Business Administration major at Haas. I am a junior on track to graduate in May of 2019. I compete on the Women’s Tennis Team at Cal. This is my first semester taking courses in the Walter A. Haas School of Business.

Zeeshan Rauf

I am a third-year Business Major at Haas. I grew up in Fresno, CA, and have taken a range of classes since coming to Berkeley in the fall of 2015. I’m graduating in May 2019 and will be working in finance in New York post-graduation.

Sofia Rivas

I am a third-year student-athlete studying Business Administration at the UC Berkeley, Haas School of Business and I intend to graduate in May of 2019. I was raised in Miami, Florida, but my family is originally from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Works Cited

Baker, Al, Colin Moynihan, and Sarah Maslin Nir. “Police Arrest More Than 700 Protesters on Brooklyn Bridge.” The New York Times. N.p., 1 Oct. 2011. Web.

Bierut, Michael. “The Poster That Launched a Movement (Or Not).” Design Observer, 30 Apr.

2012.

Brady, Jeff. “Unions Assume A Support Role For Occupy Movement.” NPR. NPR, 29 Oct. 2011. Web.

Boyle, Christina, Emily Sher, Anjali Mullany, and Helen Kennedy. “Unions Join Wall Street Protest March.” NY Daily News. N.p., 05 Oct. 2011. Web. 29 Nov. 2017.

Calhoun, C. (2013), Occupy Wall Street in perspective. The British Journal of Sociology, 64:

26–38.

Captain, Sean. “The Demographics Of Occupy Wall Street.” Fast Company. N.p., 19 Oct.

2011. Web.

Cillizza, Chris. “What Occupy Wall Street Meant (or Didn’t) to Politics.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 17 Sept. 2013. Web

Costanza-Chock, Sasha. “Mic Check! Media Cultures and the Occupy Movement.” Social

Movement Studies 11, no. 3–4 (August 1, 2012): 375–85.

Crawford, Jarret T., and Eneda Xhambazi. “Predicting Political Biases Against the Occupy

Wall Street and Tea Party Movements.” Political Psychology, 19 Aug. 2013.

Francescani, Chris. “Dozens Arrested at Occupy’s 6-month Anniversary Rally.” Reuters.

Thomson Reuters, 18 Mar. 2012. Web. 29 Nov. 2017.

Greenhouse, Steven, and Cara Buckley. “Seeking Energy, Unions Join Protest Against Wall Street.” New York Times. N.p., 5 Oct. 2011. Web.

Haberman, Clyde. “The Bull Tied to Occupy Wall Street.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 17 Sept. 2012. Web. 29 Nov. 2017.

Hayduk, Ron. “Global Justice and OWS: Movement Connections.” Socialism and Democracy

26, no. 2 (July 1, 2012): 43–50.

Idabenedetto, Reading The Pictures. “BagNewsSalon: The Visual Politics of Occupy Wall

Street.” Reading The Pictures, 10 Nov. 2017.

Milner, Ryan M.. Pop Polyvocality: Internet Memes, Public Participation, and the Occupy Wall

Street Movement. International Journal of Communication, [S.l.], v. 7, p. 34, Oct.

2013. ISSN 1932-8036. Available at: <http://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/1949/1015>. Date accessed: 15 Oct. 2017.

Kaste, Martin. “Exploring Occupy Wall Street’s ‘Adbuster’ Origins.” Npr. N.p., 20 Oct. 2011. Web.

Occupy Wall Street Group. “Occupy to Celebrate! The Resilience of OWS.” Facebook. 3 Dec. 2011. Web.

OccupyWallSt. “We Are the 99 Percent.” We Are the 99 Percent. N.p., n.d. Web. 08 Dec. 2017.

Reese, Thomas J. “Occupy Wall Street’s Most Unlikely Ally: The Pope.” Npr. N.p., 25 Oct. 2011. Web.

Ruth, Van Gelder Sarah. This Changes Everything: Occupy Wall Street and the 99% Movement. N.p.: Berrett-Koehler, 2011. Print.

Schwartz, Mattathias. “Pre-Occupied.” The New Yorker. N.p., 28 Nov. 2011. Web.

Silva, Daniella. “‘Fearless Girl’ Statue Will Face Off Wall Street Bull for Another Year.”NBCNews.com. NBCUniversal News Group, 27 Mar. 2017. Web. 29 Nov. 2017.

Slaughter, Anne-Marie. “Occupy Wall Street and the Arab Spring.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media

Company, 7 Oct. 2011.

Suppressing Protest: Human Rights Violations in the U.S. Response to Occupy Wall Street.

The Week Staff. “The Demographics of Occupy Wall Street: By the Numbers.” The Week. N.p., 20 Oct. 2011. Web.

“Their Fight Is Our Fight: Occupy Wall Street, the Arab Spring, and New Modes of Solidarity

Today.” Is This What Democracy Looks Like? N.p., n.d. Web. 29 Nov. 2017.

Watson, Tom. “Occupy Wall Street’s Year: Three Outcomes for the History Books.”Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 26 Sept. 2012. Web.

Weinstein, Adam. “‘We Are the 99 Percent’ Creators Revealed.” Mother Jones, 25 June 2017.

Westfeldt, Amy (December 15, 2011). “Occupy Wall Street’s center shows some cracks”.

BusinessWeek. Archived from the original on May 2, 2013. Retrieved February 15,

2012.

Zlutnick, David, Rinku Sen, Yvonne Yen Liu. “Where’s the Color in the Occupy Movement?

Wherever We Put It.” Colorlines, May 1, 2012.

https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=2011-09-01%202012-12-30&geo=US&q=%2Fm%2F0h63jfq

Images Cited

Bull surrounded by cops (Image 1)

MailOnline, Jill Reilly for. “A Load of Old Bull: 25 Years on, the Incredible Christmas Story of the

Guerrilla Gift Wall Street Didn’t Want – but Which Became One of NYC’s Best-Loved

Mascots Anyway.” Daily Mail Online, Associated Newspapers, 17 Dec. 2014.

OWS – What is Our One Demand (Image 2)

“Case Study: #OccupyWallStreet (Original Poster and Email).” Micah White, PhD.

https://www.micahmwhite.com/occupywallstreet/

Fearless little girl looking at bull (Image 3)

Miller, Ryan W. “‘Fearless Girl’ Statue Will Keep Staring down Wall Street’s Bull.” USA Today.

Gannett Satellite Information Network, 27 Mar. 2017. Web. 08 Dec. 2017.

Jesse Jackson (Image 4)

“Rev. Jesse Jackson To Join Occupy Cincinnati Protesters.” CBS Cleveland. N.p., 15 Nov.

2011. Web.

http://cleveland.cbslocal.com/2011/11/15/rev-jesse-jackson-to-join-occupy-cincinnati-protesters/

Kanye West (Image 5)

Perpetua, Matthew. “Kanye West Visits Occupy Wall Street Rally.” Rolling Stone, Rolling Stone,

11 Oct. 2011.

http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/kanye-visits-occupy-wall-street-rally-20111011

We are the 99% – Tumblr Page (Image 6)

http://wearethe99percent.tumblr.com/

Occupy Protest Pepper spray video – Youtube (Image 7)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TZ05rWx1pig

Occupy to Celebrate! The Resilience of OWS – Facebook Page (Image 8)

https://www.facebook.com/events/903756739686247/

Occupy Wall Street – Google Trends (Image 9)

https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=2011-08-01%202012-12-01&q=occupy%20wall%20street

[1] Hayduk, Ron. “Global Justice and OWS: Movement Connections.” Socialism and Democracy 26, no. 2 (July 1, 2012): 43–50.

[2] Slaughter, Anne-Marie. “Occupy Wall Street and the Arab Spring.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 7 Oct. 2011.

[3] Milner, Ryan. “Pop Polyvocality: Internet Memes, Public Participation, and the Occupy Wall Street Movement.” International Journal of Communication[Online], 7 (2013): 34. Web. 15 Dec. 2017

[4]Ibid.

[5] Idabenedetto, Reading The Pictures. “BagNewsSalon: The Visual Politics of Occupy Wall Street.” Reading The Pictures, 10 Nov. 2017.

[6] Haberman, Clyde. “The Bull Tied to Occupy Wall Street.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 17 Sept. 2012.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] MailOnline, Jill Reilly for. “A Load of Old Bull: 25 Years on, the Incredible Christmas Story of the Guerrilla Gift Wall Street Didn’t Want – but Which Became One of NYC’s Best-Loved Mascots Anyway.” Daily Mail Online, Associated Newspapers, 17 Dec. 2014.

[10] Haberman, Clyde. “The Bull Tied to Occupy Wall Street.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 17 Sept. 2012. Web. 29 Nov. 2017.

[11] “Case Study: #OccupyWallStreet (Original Poster and Email).” Micah White, PhD.

[12] Milner, Ryan M.. Pop Polyvocality: Internet Memes, Public Participation, and the Occupy Wall Street Movement. International Journal of Communication, [S.l.], v. 7, p. 34, Oct. 2013.

[13] Bierut, Michael. “The Poster That Launched a Movement (Or Not).” Design Observer, 30 Apr. 2012.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Miller, Ryan W. “‘Fearless Girl’ Statue Will Keep Staring down Wall Street’s Bull.” USA Today. Gannett Satellite Information Network, 27 Mar. 2017. Web. 08 Dec. 2017.

[16] Silva, Daniella. “‘Fearless Girl’ Statue Will Face Off Wall Street Bull for Another Year.” NBCNews.com. NBCUniversal News Group, 27 Mar. 2017. Web. 29 Nov. 2017.

[17] Hayduk, Ron. “Global Justice and OWS: Movement Connections.” Socialism and Democracy 26, no. 2 (July 1, 2012): 43–50.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Hayduk, Ron. “Global Justice and OWS: Movement Connections.” Socialism and Democracy 26, no. 2 (July 1, 2012): 43–50.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Westfeldt, Amy (December 15, 2011). “Occupy Wall Street’s center shows some cracks”. BusinessWeek. Archived from the original on May 2, 2013. Retrieved February 15, 2012.

[23]Boyle, Christina, Emily Sher, Anjali Mullany, and Helen Kennedy. “Unions Join Wall Street Protest March.” NY Daily News. N.p., 05

Oct. 2011. Web. 29 Nov. 2017.

[24]Francescani, Chris. “Dozens Arrested at Occupy’s 6-month Anniversary Rally.” Reuters. Thomson Reuters, 18 Mar. 2012. Web. 29 Nov. 2017.

[25] Captain, Sean. “The Demographics Of Occupy Wall Street.” Fast Company. N.p., 19 Oct. 2011. Web.

[26] Pearce, Matt. “Many Occupy Protesters Well-off, White and Educated, Study Says.” Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles Times, 29 Jan. 2013, articles.latimes.com/2013/jan/29/nation/la-na-nn-occupy-wall-street-study-20130129.

[27] “Occupy Wall Street’s Message Doesn’t Resonate with All of the 99%.” WNYC, 4 Nov. 2011, www.wnyc.org/story/168626-blog-occupy-wall-street-poor

[28] “Occupy Wall Street’s Message Doesn’t Resonate with All of the 99%.” WNYC, 4 Nov. 2011, www.wnyc.org/story/168626-blog-occupy-wall-street-poor

[29] “Rev. Jesse Jackson To Join Occupy Cincinnati Protesters.” CBS Cleveland. N.p., 15 Nov. 2011. Web.

[30] Perpetua, Matthew. “Kanye West Visits Occupy Wall Street Rally.” Rolling Stone, Rolling Stone, 11 Oct. 2011.

[31] Reese, Thomas J. “Occupy Wall Street’s Most Unlikely Ally: The Pope.” Npr. N.p., 25 Oct. 2011. Web.

[33] Weinstein, Adam. “‘We Are the 99 Percent’ Creators Revealed.” Mother Jones, 25 June 2017.

[34]OccupyWallSt. “We Are the 99 Percent.” We Are the 99 Percent. N.p., n.d. Web. 08 Dec. 2017.

[36]“Their Fight Is Our Fight: Occupy Wall Street, the Arab Spring, and New Modes of Solidarity Today.” Is This What Democracy Looks Like? N.p., n.d. Web. 29 Nov. 2017.

[37]Slaughter, Anne-Marie. “Occupy Wall Street and the Arab Spring.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 7 Oct. 2011.

[40] “Remarks by the President in State of the Union Address.” National Archives and Records Administration, National Archives and Records Administration, 24 Jan. 2012, obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2012/01/24/remarks-president-state-union-address.

[41] Agarwal, Sheetal D., Michael L. Barthel, Caterina Rost, Alan Borning, W. Lance Bennett, and Courtney N. Johnson. “Grassroots Organizing in the Digital Age: Considering Values and Technology in Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street.” Information, Communication & Society 17, no. 3 (March 16, 2014): 326–41.

[42] Skocpol, Theda, and Vanessa Williamson. The Tea Party and the Remaking of Republican Conservatism. Oxford University Press, 2011. (Introduction and Chapter 4)

[43] Jossey, Paul H., et al. “How We Killed the Tea Party.” POLITICO Magazine, 14 Aug. 2016,

[44] Costanza-Chock, Sasha. “Mic Check! Media Cultures and the Occupy Movement.” Social Movement Studies 11, no. 3–4 (August 1, 2012): 375–85.

[45] Costanza-Chock, Sasha. “Mic Check! Media Cultures and the Occupy Movement.” Social Movement Studies 11, no. 3–4 (August 1, 2012): 375–85.

[46] Calhoun, C. (2013), Occupy Wall Street in perspective. The British Journal of Sociology, 64: 26–38.

[47] Zlutnick, David, Rinku Sen, Yvonne Yen Liu. “Where’s the Color in the Occupy Movement? Wherever We Put It.” Colorlines, May 1, 2012.

[48] http://occupywallst.org/

[49] Hayduk, Ron. “Global Justice and OWS: Movement Connections.” Socialism and Democracy 26, no. 2 (July 1, 2012): 43–50.

[50] Slaughter, Anne-Marie. “Occupy Wall Street and the Arab Spring.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 7 Oct. 2011.