Introduction

This chapter of the Berkeley Guide to Social Movements and Social Media explores and analyzes the Women’s Rights Movement, a social movement advocating for women’s rights and equalities within the United States of America. Over time, more specific and individualized variations of this movement have manifested, including the Feminist Movement, the Women’s Movement, and the Women’s Liberation Movement. In the United States, women have successfully managed to gain property rights, voting rights, reproductive rights, and equal pay rights by uniting together to achieve their common goal of women’s equality.[1]

The Women’s Rights Movement has evolved and advanced over the course of history due to the advent of new technology, specifically social media platforms. In order to spread information as quickly and efficiently as possible and to reach a large audience, social movement organizers have effectively utilized various social media platforms as their main tool. The Women’s Rights Movement has existed for over a century, marking its beginning on July 13, 1848 in New York City, when 300 men and women collectively signed the Declaration of Sentiments in effort to end gender discrimination.[2],[3] For almost 170 years, people have been advocating that women must be seen and treated equal to their male counterparts. This chapter focuses on how social media platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, have amplified and strengthened the Women’s Rights Movement, allowing for the faster distribution of information, the spread of awareness, the increase in visibility, and the organization of offline events.

Context

As stated earlier, the Women’s Rights Movement dates back to the signing of the Declaration of Sentiment on July 13, 1848.[4] However, it is important to note that the discrimination against women existed long before and after this declaration was signed. There have been four main waves of feminism throughout U.S. history.

The serious discussion of women’s rights began in the 19th century, known as the first ware of feminism. In the United States, women were primarily focused on gaining the right to vote. White, middle class women held conventions, like the Seneca Falls Convention, where they openly discussed the issue gender discrimination. Newspapers wrote about the conventions and women’s rights, resulting in the formation of an annual women’s rights convention in America. Other women read about the fight for women’s rights and subsequently joined the movement.[5]

The second wave of feminism took place immediately after World War II in 1960. This wave was concerned more with women’s sexuality and equal rights. People involved in this movement fought for the passing of the Equal Rights Amendment, which would allow equal rights to people in the United States regardless of sex or race. Unlike the first wave, the people involved in the second wave had a vast variety of different socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic backgrounds.[6]

Shortly after the second wave of feminism, the third wave of feminism began in the mid- 1990s, which addressed society’s controversy with the sexualization of a woman’s body and the way women dressed. Women during this time wanted to be perceived by men as equally strong and empowered, so they did not associate themselves with the term “feminist” and they rejected ideas of sexuality norms that were normally forced upon them.

We are currently in the midst of the fourth wave of feminism. Men have now also joined the movement. The negative connotation that surrounds the word feminist still exists, and there is now the perception that all feminists are extremists and radicals.[7] Women involved with the movement do not want feminism to only be about women’s struggles in society, but instead they are focused on promoting and supporting gender equality.[8]

History

The following timeline is a list of the most noteworthy events advocating for women’s rights:[9]

Timeline

1777

State laws were passed, denying women their right to vote.

1848

At Seneca Falls, New York, 300 women and men sign the Declaration of Sentiments.

1890

Wyoming was the first state to grant women the right to vote.[10]

1920

The Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution was ratified, granting women the right to vote.

1963

The Equal Pay Act passed, guaranteeing equal wages for equal work regardless of sex, race, or religion.

1964

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act passed, which prohibited sex discrimination in employment.

1968

President Lyndon B. Johnson signed an order which required affirmative action plans for women and prohibited sex discrimination by government contractors.

1973

Abortion becomes legal in the United States.

1978

The Pregnancy Discrimination Act was passed which banned employment discrimination against pregnant women.

1981

“Sandra Day O’Conner becomes the first woman to serve on the Supreme Court.”

1997

“Madeleine Albright became the first female secretary of state.”

2017

The Women’s March on Washington took place country wide in January 2017 which advocated for women’s equality shortly after President Trump entered the White House.

Google Trend

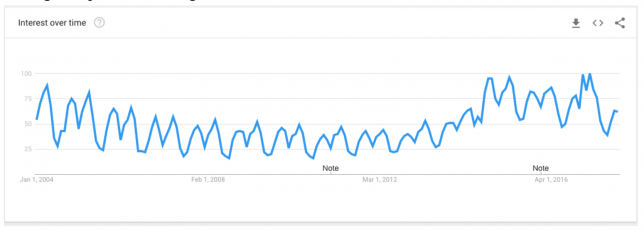

When conducting a Google Trends search for the word “feminism,” from January 2004 to the present, we found several notable dates. There is a clear inflection point in March 2014, where the word feminism reached its peak up until that date. The word was searched many times due to the Yes All Women Movement, which was a popular hashtag campaign that was used to discuss sexism and misogyny against women. As seen below, there are two spikes in searches, in 2017. The second to highest spike to this date is in January 2017, when Trump was inaugurated. The highest spike in the Google Trends Search is in March 2017.

Key Actors

Key actors involved in the Women’s Rights Movement date back to the 18th century. One of the most well-known activists in Women’s Rights Movement is Susan Anthony (1820-1906). She was a Quaker whose parents believed that men and women should get an education. Anthony fought for women to have equal rights as men, preaching for women’s suffrage. She believed that all women, regardless of race or ethnicity, should be equally protected under the law. [13] Other well-known activists include Mary Wollstonecraft, Alice Stone Blackwell, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Emmeline Pankhurst, Sojourner Truth. These women were collectively known as The Suffragettes.[14]

Other important activists during the 19th century include Eleanor Roosevelt and Betty Friedan. Eleanor Roosevelt (1884-1962) is another key figure who fought for women’s rights. Roosevelt was not only the First Lady, but she was also active in the Women’s Rights Movement. She founded the Women’s Trade Union League and the International Congress of Working Women. Roosevelt felt strongly about the treatment of women in America and wrote a newspaper article called “My Day,” which discussed women’s equality in the workforce. In addition to all these accomplishments, Roosevelt was also the first female U.S. Delegate to the United Nations. Betty Friedan’s work and organization of the Women’s Strike for Equality in 1970, popularized feminism in America.[15] Friedan organized a parade where 50,000 women came together for the 50 year anniversary of the 19th amendment.[16]

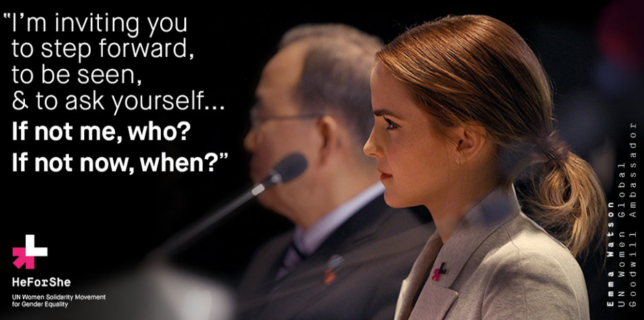

The advent of social media is a large contributor to the growth of this movement. Celebrities have used and continue to use social media platforms as a means to connect with the public and address issues of women’s rights. The long list of celebrity activists includes but is not limited to Barbara Walters, Hillary Clinton, Oprah Winfrey, Beyoncé, and Emma Watson. Barbara Walters was the first female co-host of a news show and first female co-anchor of a news broadcast for ABC News. Walters promoted women in the workforce, influencing other women to fight for high ranking jobs.[17] Hillary Clinton was not only a First Lady, but was also an elected public servant. Clinton became the first female presidential candidate nominated by a major party in 2016. She advocated for women to have leadership roles and to be involved in political roles.[18] Oprah Winfrey’s talk show and success was a huge stride towards equality for African American women. Winfrey was also a influential advocate for women’s rights and fought for equal pay for women in the workforce.[19] Beyoncé has used her large following and celebrity status to discuss power in pop culture. Beyoncé considers herself to be an active feminist and openly discusses the importance of female empowerment in her songs. She works to remind her fans the importance of women equality.[20] Emma Watson is another key activist, contributing greatly to the #heforshe movement, which advocates for gender equality. Watson delivered a speech at the United Nations headquarters, saying that feminism isn’t just a fight for women, and that men should join the movement as well.[21]

Emma Watson’s tweet about her speech for the #heforshe campaign. [22]

Emma Watson’s tweet about her speech for the #heforshe campaign. [22]

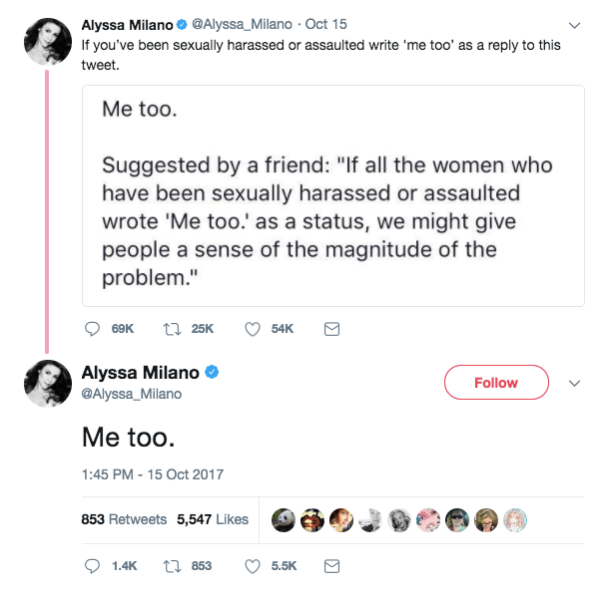

Lady Gaga has used Twitter as a forum to express the issue of sexual assault with women. Gaga took part of the #MeToo campaign, which quickly went viral on social media. People posted statuses and tweeted #MeToo to say if they had ever been sexually assaulted, or to show support for victims of sexual assault. This showed the public how many women have been dehumanized and sexually assaulted by other men.

Tweet from Lady Gaga, supporting the #MeToo campaign. [23]

Social Media Presence

Platforms Used

The 21st century is characterized by the fourth wave of feminism due to the advent of the Web 2.0, where endless advancements in technology— especially in the Internet and social media applications— have given women the agency to form their own content and to share them at an unimaginable scale.[24] Thus, the Women’s Rights Movement has gradually shifted from physical spaces to the digital sphere, as “cyberfeminism” continues to gain momentum.

The public launches of both Facebook and Twitter in the mid 2000s revolutionized pre-existing transnational media outlets such as CBS, News Corp, and Al Jazeera, amongst others. These social media platforms introduced digital spaces where anyone with Internet access could engage in “trending” sociopolitical movements and mingle with “networked individuals” in the fifth estate. “Networked feminists,” feminists who mobilize and coordinate in online communities to fight against perceived sexist, misogynistic, racist, and other discriminatory acts against minority groups, have embraced these two new online platforms, utilizing them to resist the traditional patriarchy and to disseminate modern feminist ideals.[25]

The primary social media platforms that have been used to advance the Women’s Rights Movement are Facebook and Twitter. Instagram, Tumblr, Pinterest, Google+ and other blogs have also played a role, but to a much smaller extent and in a less impactful way. According to data from Twitter, the past three years saw a 300% increase in conversations surrounding feminism on the platform.[26] Moreover, in 2013, the Pew Research Center revealed one of the largest audience for online feminists of all time, with over 74% of women on the Internet using social media outlets.[27]

Popular Hashtags

The effectiveness of social media outlets Twitter and Facebook have paved the way for an unstoppable force in the Women’s Rights Movement: hashtag (#) activism. Hashtag activism, a term coined by media outlets, pertains to the use of hashtags on social media platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram, to drive internet activism.[28] While the hashtag initially originated from a need to collect related stories regarding specific events, it is now used on a global-scale by feminists to share their stories and enact widespread change. Hashtags supporting the Women’s Rights Movement have spurred both large scale and small scale Internet activity in the community.

Large Scale

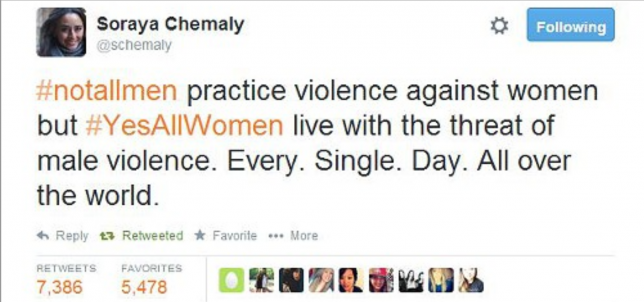

#YesAllWomen

In May 2014, Twitter exploded when millions of people started tweeting #YesAllWomen — a social media campaign began by Muslim activist Kaye M., which sought to catalyze discussions on the universality of violence, misogyny, and sexism against women.[29] This time period marked the tipping point for hashtag feminism. This hashtag first appeared on online platforms in response to the hashtag #NotAllMen, a feminist internet meme following Elliot Rodger’s 2014 Isla Vista killings used to defend men in gendered criticisms of their behavior. In his YouTube video titled “Elliot Rodger’s Retribution,” Rodgers revealed that his shooting spree at the Alpha Phi sorority house stemmed from his desire to “punish women for rejecting him.”[30] While some Twitter users argued that “not all men” are like Rodgers, supporters of #YesAllWomen saw those arguments as dismissive of uncomfortable topics like violence and sexism toward women.

The virality of the hashtag garnered a massive grassroots response, as users from all over the world shared personal anecdotes of discrimination, terror, and harassment to highlight the fact that “Yes All Women” are affected by sexism and misogyny, even though not all men commit such crimes. Beginning in the United States, the movement quickly spread around the world to Europe, South Africa, Brazil, Australia, and Japan. Within four days of the original #YesAllWomen post, the hashtag was tweeted 1.2 million times and surpassed predecessors that also drew attention to these taboo topics. At its peak, over 51,000 #YesAllWomen tweets were sent per hour.[31]

Image showcasing an example of a #YesAllWomen tweet found in Roxanna Bennett’s article.[32]

Image showcasing an example of a #YesAllWomen tweet found in Roxanna Bennett’s article.[32]

#HeForShe

In September 2014, UN Women created a solidarity campaign under the hashtag #HeForShe to encourage men and boys to advance gender equality by taking action against injustices faced by women and girls. The movement addressed a reality that transcends social, economic, and political bounds— all people are impacted by gender equality. #HeForShe conveyed the notion that feminism should no longer be perceived as a “struggle for women by women,” but rather as an issue impacting all genders. Hence, women’s empowerment is essential for economic growth, social cohesion and social justice, environmental balance, and progress in all spheres of life. [33]

Perhaps the most well-known representative of the #HeForShe campaign was Harry Potter actress Emma Watson, who delivered a monumental speech as the UN Women Goodwill Ambassador that went viral. Watson’s celebrity status and large social media presence, along with the support from high-profile male champions like President Barack Obama and actor Matt Damon, allowed the viral speech to garner over 11 million viewers standing in solidarity for gender equality.

With the initial goal to mobilize 100,000 men and boys within a year, #HeForShe secured that many supporters within just three days. In less than two weeks after the launch, #HeForShe reached 1.2 billion unique Twitter users through 1.1 million #HeForShe tweets by more than 750,000 different people.[34] Contrasting typical social media campaigns that quickly dissolve, #HeForShe continues to capitalize on celebrity endorsements to reach long-term levels of success. The campaign has united nations in global discussion by regularly utilizing its streamlined channels to engage followers and to educate them on the progress.

Image of Emma Watson giving a speech at a HeForShe UN conference found on hootsuite.com.[35]

Despite its apparent success, the #HeForShe campaign received heavy criticisms from the general public. For example, the hashtag #HeForShe was denounced as reinforcing gender binaries. By using the pronouns “he” and “she” those who do not identify with either of these two genders are automatically excluded from this campaign. Additionally, there have been suggestions that “Stand With Women” would have been a more appropriate name for the campaign. Rather than emphasizing the need for stronger male allies to stand up for weaker women, the name would imply that men are standing alongside women in the battle for gender equality. Additionally, the transgender community and people of color are both excluded from this campaign.

#MeToo

Editor’s Note: After this chapter was completed, #MeToo became one of the most successful social movements to leverage social media in history. This was recognized with the naming of the Silence Breakers as the 2017 People of the Year by Time Magazine. #MeToo started trending and went viral during the writing of this chapter, so unfortunately, not all of the information about the background and impact of the hashtag was available before this chapter was published. For more information about the #MeToo movement, see Time Magazine and Wikipedia, on #MeToo.

The #MeToo campaign was created to draw attention to the topic of sexual harassment and assault. This movement was so powerful that Time magazine listed it as the “most influential “person” in 2017.”[36] This movement, growing by multiple courageous individuals coming forward to share their stories, is said to be the fastest moving social change seen in a long time. This movement and hashtag goes beyond Twitter, with people posting the #MeToo on other social media platforms, like Facebook. Many celebrities like Lady Gaga and Alyssa Milano have participated in using the hashtag to spread awareness on sexual harassment.[37]

Celebrity Alyssa Milano took part of the #MeToo movement on Twitter[38]

Small Scale

#FreeTheNipple

Actress Lina Esco, the organizer of the 2014 “Free the Nipple” campaign, began the movement in an effort to spark discussions on gender inequality. While the name itself holds a comedic ring, “Free the Nipple” brings attention to more serious topics, like taboo public nudity laws and sexist double-standards.[39] The movement argues that female nudity is not only about sexualization, but also about dismantling society’s male-dominated hierarchy. “Free the Nipple” alludes to the irony in the acceptance of female nudity in pornography and other acts of public shame, and its rejection as a form of non-sexual female power, like breastfeeding.[40] The movement took over Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter and is supported by celebrities Miley Cyrus, Rihanna, and Jennifer Aniston. On Facebook, moderators rigorously remove any content related to breastfeeding, labor, childbirth, and reproductive health from their website. Moreover, it is it is completely illegal for women to appear topless in three states and otherwise socially unacceptable in the rest of the nation.[41]

Image of women standing in solidarity during the Free the Nipple movement[42]

While the “Free the Nipple” movement aims to fight social media censorship and uncover double-standards in male and female body perceptions, critics argue that #FreeTheNipple has not gained significant traction in regards to new legislation. In over three years, 3-million Instagram entries, and one documentary later, the hashtags have merely become a digital fad. LGBTQ campaigners and feminist groups argue that the movement caters to the select few white, skinny, cis, and able-bodied women who already fit society’s mold of beauty. Opponents argue that disabled, mutilated, and transgender women who digress from typical female bodies are not liberated when they expose their breasts. Instead, because their breasts are deemed not femme enough to censor, they are subject to countless criticisms facilitated online, further reinforcing oppressive gender constructs in the community. Moreover, the official merchandise for #FreeTheNipple portrays perky B-cup breasts, excluding other varieties of breast shapes prevalent throughout the nation. This campaign thus only provides a platform for an exclusive group of women.[43]

#StandWithWendy

In 2013, local women rallied together at the Texas State capital to support State Rep. Wendy Davis through her 13-hour filibuster aimed at protesting the Senate Bill 5, an bill in Texas that would ben abortions at 20 weeks.[44] Davis’ filibuster successfully stopped Republicans from passing the bill by the midnight deadline, attracting hundreds of jeering protesters who crowded the capitol to help the cause.

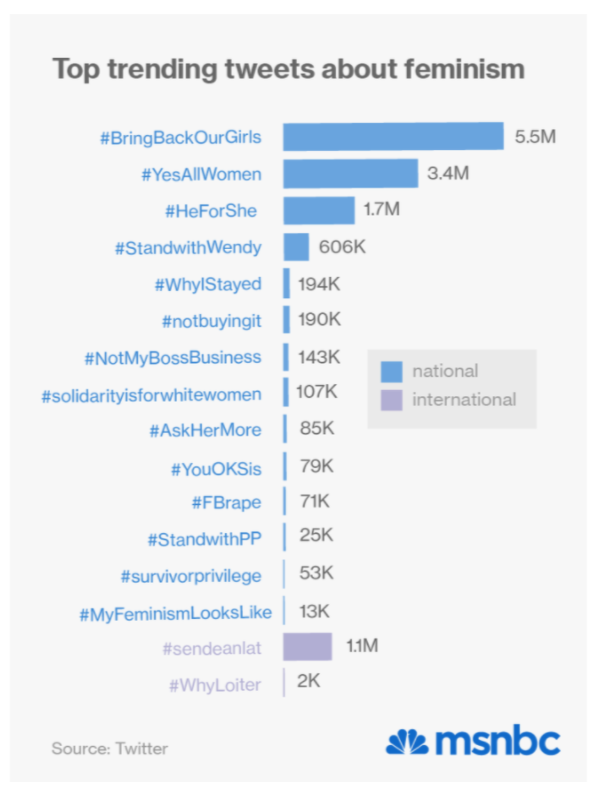

Other relevant hashtags include #BringBackOurGirls, #MeToo, #EverydaySexism, #WhyIStayed, #AskHerMore, #NotBuyingIt, and #ChangeTheRatio, amongst others.

Twitter image of MSNBC trending tweets about feminism[45]

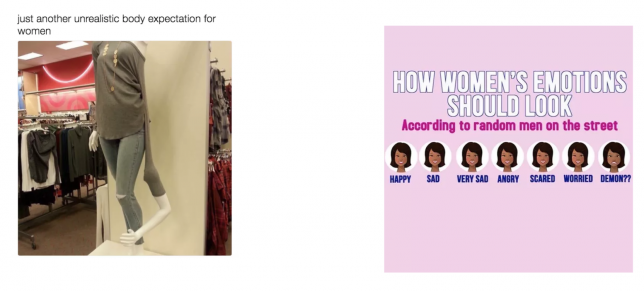

Meme vs. Cause

In today’s day and age meme culture plays a large role within our society. With the rise of Internet, memes have become more popular and widespread than ever before. It is important to note, however, that memes have existed for quite some time and only gained momentum with the rise of social media. When internet and technology were not as dominant as they are today, memes, or rather caricatures, were widely spread in newspapers pamphlets and postcards.[46] Today, the spread of images ridiculing or drawing attention to serious issues can be found on various social media platforms as well as printed on merchandise such as t-shirts and computer stickers. Memes are an important tool in providing entertainment and drawing attention to specific issues.

In terms of the Women’s Rights movement, there are several memes showcasing various issues concerning gender equality or how women are perceived within the online and offline spheres. As seen in the images below the first image addresses, in a rather humorous way, the unrealistic expectations women are confronted with on a daily basis by the media using photoshop to create extreme or unattainable body images. The second image draws attention to how women are perceived by men, again due to media’s influence in terms of how women are presented, and how they should therefore act and look a certain way when in public. The third and last image draws attention to specific words that include some sort of connection to the male persona. Various memes showcase a play on words by changing words such as history to herstory, and as can be seen in the meme below the word Amen has been changed to Awomen. Overall, memes are a great way of drawing attention to critical issues. By addressing issues in a humorous way attention can be drawn to certain topic without offending anyone. As humorist Mary Hirsch stated “Humor is a rubber sword – it allows you to make a point without drawing blood.”[47]

All three images of different memes can be found in Hattie Soykan’s article.[48]

Most Important Twitter Hashtags

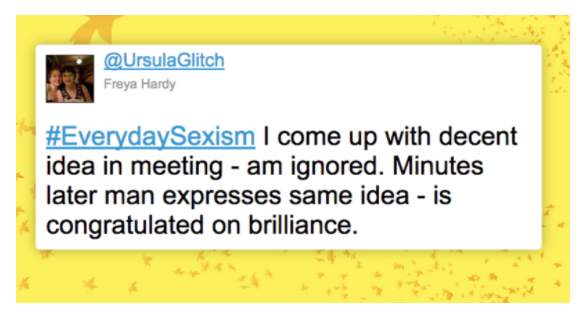

Twitter is a social media platform, which is well known for its “hashtivism.” The platform is used by millions of people using various hashtags to either create or show support for movement. The following list showcases important and heavily used hashtags on Twitter:

-

#IAmANastyWoman: This hashtag came about shortly after Donal Trump referred to Hillary Clinton as a “nasty woman.” People took to Twitter, hashtagging Trump’s words and defending women who speak their minds. The hashtag spread quickly online, due to the fact of many women related to being called similar names for speaking their mind and standing up for their thoughts and actions.[49]

-

#EverydaySexism: This hashatag was used by women sharing their personal experiences of being exposed to sexism. By using this hashtag, individuals shared everyday life stories as well as examples of discrimination within their workplace.[50]

The tweet above showcases an example of a Twitter user implementing the #EverydaySexism hastag.[51]

The tweet above showcases an example of a Twitter user implementing the #EverydaySexism hastag.[51]

-

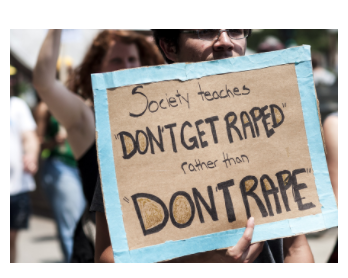

#RapeCultureIsWhen: The term “rape culture” was coined in the 1970s by American feminists creating an umbrella term to summarize the normalization of sexual assault against women in cultural attitudes. More specifically, the term is supposed to showcase how society normalizes sexual violence performed by men, whereas women are blamed when becoming a target of sexual assault. Decades later, this term was created into a hashtag to help raise awareness on how women are blamed when falling victim to sexual assault.[52]

This image showcases a person holding a self made poster captured by cultivatingculture.com[53]

-

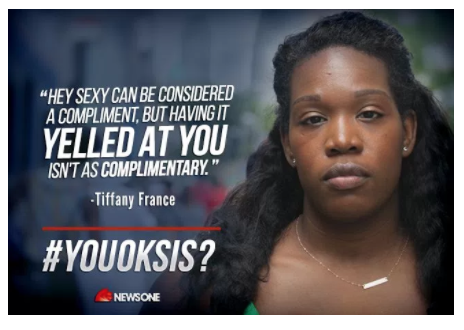

#YouOkSis: This hashtag was created by blogger Feminista Jones to counter street harassment to which women are exposed to on a daily basis. This hashtag was invented to open up communication between African American individuals on this topic; sharing their experiences with each other as well as search for possible solutions to stop street harassment.[54]

This image, found on wordpress.com, shows a statement of Tiffany France giving an example of street harassment[55]

Analysis of Importance

While social media played a crucial role in amplifying this movement online, much more must be done for women to visibly impact decision-making processes offline.

Before the creation of social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter, it was extremely difficult to fight sexism in public spaces. There was a lack of open forums where women could discuss feminism, and many women’s rights have been negatively stigmatized as “feminazis” by celebrities like Katy Perry, Shailene Woodley, and Rush Limbaugh.[56] Without digital platforms for organizing social movements, dispersing information, and fostering communities, only people in those cities or within the vicinity at the time could participate in feminist rallies. In addition, only those who could afford the luxury of skipping work to travel to the rallies could access these campaigns. However, social media has completely transformed this complicated process and has expedited what once took months of traditional pre-planning to a simple click of a button.

The current onset of the fourth wave of feminism has redefined digital expression for feminist practice and theory. Fringe blogs made way for Facebook and Twitter microblogs, and feminism became a viral “trend” in the technological realm. Moreover, social media platforms fostered a sense of global solidarity and made feminist conversations easily accessible through “logging in” to personalized accounts. Thus, instead of minimizing their thoughts into a single think-piece, women could now actively contribute to discussions in real-time and constructively voice their opinions in an engaging community. With this, social media instilled a sense of transnational belonging and confidence in women and young girls. More people than ever are proud to declare themselves as feminist or feminist allies, with numbers growing exponentially every year.

Perhaps the true power of social media stems from the ability for members to share stories that oppose the silencing of women and minority groups. By speaking up in these digital spaces, women are effectively regaining their agency and autonomy. For example, after women’s rights groups adamantly resisted Victoria’s Secret’s “perfect body” slogan through Twitter and Change.org petitions, the company adjusted its white-dominated advertising campaign and changed its slogan to avoid promoting negative body images.[57] Additionally, women are now pushing for greater accountability, using social media as a tool to collaborate on projects to further feminist goals. This is evident on a worldwide scale, as Egyptian women took a stand against sexual abuse by creating a HarassMap app to fight against sexual assault.

Nonetheless, since this change only began in the last decade, more efforts must be made to enact tangible changes for the Women’s Rights Movement. Many individuals confuse online activism with real life activism, a term dubbed slacktivism, that detracts from opportunities to mobilize on a giant scale. This is essential because online and offline participation must work hand-in-hand to create the greatest impact possible.

Organic vs. Planned growth

Due to the lack of technology at the start of the Women’s Rights Movement, the movement highly depended on planned growth to raise awareness surrounding gender equality. Supporters primarily utilized meticulous planning through traditional communication such as letters, physical meetups, and phone calls to organize key events. This deliberate growth was evident on a national-scale, as women utilized the Seneca Falls Convention and the signing of the Declaration of Sentiments to advance the feminist agenda. On a local scale, this time period saw activism in the form of local rallies, protests, and marches organized through word of mouth. Examples include the Seneca Falls Convention and Women’s Suffrage Movement, among others.

However, since the emergence of the digital era and the advent of social media platforms, the Women’s Rights Movement has taken a direction toward more natural and unpredictable growth. During the current fourth wave of feminism, viral hashtags and widespread memes have easily raised awareness for feminist ideals at speeds and on scales never seen before. More importantly, social media has democratized women’s rights activism by dismantling physical barriers of geography, time zones, and distance.

Sites such as Reddit, 4chan, Quora, Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook are web platforms where constructive conversations on feminism take place with the click of a button. This means that anyone with a social media account and access to the Internet can participate in the fight against patriarchal structures of power, making activism and public dialogue more readily available than ever. In effect, awareness has risen tenfold as more members in society became exposed to these discussion, facilitating opportunities to collectively push for positive change. Due to such accessibility, this generation has experienced and witnessed an uncontrolled upward trend in grassroots movements and calls-to-action, as their desire for online activism has trickled into their offline personas as well.

Nonetheless, despite its organic online growth, the movement still utilizes planned offline activism— as evident from the Women’s March on Washington and SlutWalk— to achieve its overall feminist agenda. SlutWalk is the transnational movement resulting from Toronto Police officers’ claim that “women should avoid dressing like sluts” to avoid sexual assaults.[58] It fights against the justification of rape using a woman’s appearance, slut shaming, and victim blaming. Moreover, singular planned events, such as the Million Mom March, were created strictly through word of mouth.[59] In this grassroots movement, almost a thousand female participants organized in Washington D.C. to call for stricter gun control through news conferences rather than the web.[60] While most of the growth for the Women’s Rights Movement generally depends on social media platforms, it is important to not to discount the strides the movement has also made offline in physical spaces.

Offline Presence

While the majority of offline presence for the Women’s Rights Movement took place before the advent of social media platforms, the past decade has seen a few noteworthy protests that proved the significance of collective participation and physical attendance.

Women’s March 2017

The largest single-day protest in U.S. history, known as the Women’s March, or Women’s March on Washington, occurred on January 21, 2017 immediately following Donald Trump’s inauguration as the President of the United States. This drastic response was largely due to President Trump’s statements and stances that were regarded by many as offensive and anti-women. The movement began from a single Facebook post by Hawaiian organizer Teresa Shook, and quickly spread into 408 planned marches across the nation and 198 marches in 84 other countries.[61],[62] It drew between 450,000 and 500,000 participants to the nation’s capital and garnered over five million worldwide participants of all racial and socioeconomic racial backgrounds.

This image from Yahoo.com shows the Women’s March on Washington after President Trump’s election.[63]

The Women’s March on Washington rallied for the protection of various women’s rights including reproductive rights, LGBTQ rights, immigration reform, religious discrimination, health care reform, and equal pay.[64] Though it started with an online post, the movement primarily utilized the Pussy Hat Project, signage, and high-profile celebrity figures to support the cause. The Pussy Hat Project aimed to hand out millions of pink hats at the march to make a unified statement and reclaim the derogatory term “pussy” in direct opposition to Trump’s 2005 assertion that women should allow him to “grab them by the pussy.”[65] Noteworthy attendees who made statements in support of the Women’s March on Washington include singer Beyoncé Knowles, U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders, U.S Secretary of State John Kerry, and actress Scarlett Johansson.[66]

While the movement experienced a division from racial tensions during the march, it was undeniably a crucial stepping stone for the Women’s Rights Movement because it demonstrated the sheer number of female and male supporters who put the goal of womanhood above all else.[67] The Women’s March on Washington did not discriminate against any participants and sent a strong message—America must stand in solidarity against hate. It proved that the feminist movement was strong on both online and offline platforms and could address tougher, more intersectional conversations.

CODEPINK: Women for Peace

Founded in Fall 2002, CODEPINK is a women-led grassroots movement aimed at redirecting US militarism funds toward socially uplifting causes including education, healthcare, green occupations, and other life-affirming initiatives. It is an NGO that seeks to hold war criminals accountable for their actions without the use of torture, weaponized spy drones, and detainment in Guantanamo Bay.[68] In the past, CODEPINK actively rejected U.S. war in Afghanistan and Iraq, seeking peace as an alternative. This movement did not supported the persecution of whistleblowers nor the Israeli occupation of Palestine and other repressive regimes.[69]

Women holding CODEPINK posters in front of the White House by codepink.org[70]

Women holding CODEPINK posters in front of the White House by codepink.org[70]

CODEPINK began on November 17, 2992 when organizers Medea Benjamin, Jodie Evans, Diane Wilson, Starhawk, and 100 other women set up a 4-month all-day vigil in front of the White House.[71] The movement largely depended on a network of local organizers and generous donors who used satire, creative visuals, civil resistance, and street theatre to organize participants under the cause. While it also incorporated online supporters and online communication, its primary power came from its effective internal processes, coalition work, relationship-building, and conflict resolution seen offline. These included banners, flyers, press releases, and media training for local communities. The organization adhered to the Pink Action Principles of nonviolence, responsibility and teamwork, resource sharing, long-term vision global community, and diversity and tolerance. Similar to the Women’s March on Washington, participants wore pink to signify their solidarity against global militarism. The name stems from the Bush Administration’s color-coded homeland security alerts, which represented terrorist threats to the nation.[72]

Being mainly an offline movement, CODEPINK accumulated over 10,000 people to participate in their strikes circling the perimeter of the White House in November of 2002. Since then, CODEPINK has migrated overseas in order to strengthen their work to potentially end United States wars and minimize militarism. This movement has been brought to Iran, Israel-Palestine, Cuba, and other places where conflict arises in order to gain engagement and awareness. CODEPINK strides to bring awareness on the issues they discuss and make efforts to participate in international forums on peace and war.[73]

CODEPINK’s long term vision is to ensure what they call “peace economy,” which is a global community where people respect one another and help end the suffering in the world. They believe that this can be achieved by strengthening home relationships and through outside activism.[74]

Women protesting for CODEPINK by codepink.org[75]

Impact of Movement

Due to the popularity and longevity of the Women’s Rights Movement, multiple acts and policies have been passed to ensure gender equality in the workplace, government, academic space, etc.

-

Policy Achievements

- 1890 – Wyoming is the first state to grant women the right to vote in all elections

- 1900 – Every state has passed legislation granting married women the right to keep their own wages and to own property in their own name

- 1916 – Jeannette Rankin is the first woman to be elected to the U.S. House of Representatives

- 1920 – Women are granted the right to vote due to the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in the Constitution

- 1923 – The Equal Rights Amendment is introduced, stating “Men and women shall have equal rights throughout the United States and every place subject to its jurisdiction.”

- 1963 – Congress passes The Equal Pay Act for all workers, ensuring equitable wages for the same work, regardless of the race, color, religion, national origin or sex

- 1964 – Sex discrimination is employment is prohibited with the passing of Title VII in the Civil Rights Act. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission is created.

- 1965 – The Supreme Court establishes the right for married couples to use contraception.

- 1969 – The nation’s first “no fault” divorce law, a law that allows divorce by mutual consent, is adopted by California

- 1972 – Sex discrimination in all aspects of education programs that receive federal support is prohibited by Title IX of the Education Amendments

- 1974 – Congress outlaws housing discrimination on the basis of sex and credit against women. The Supreme Court rules it is illegal to force pregnant women to take maternity leave on the assumption they are incapable of working in their physical condition.

- 1975 – The right to exclude women from juries is prohibited by the Supreme Court

- 1978 – Employment discrimination against pregnant woman is banned by The Pregnancy Discrimination Act

- 1986 – The U.S. Supreme Court rules that a work environment can be declared hostile or abusive due to discrimination based on sex

- 1994 – The Violence Against Women Act gives women the right to seek civil rights remedies for gender-related crimes and funds services for victims of rape and domestic violence

- 2012 – The Paycheck Fairness Act, meant to fight gender discrimination in the workplace, fails in the Senate on a party-line vote. Two years later, Republicans filibuster the bill (twice).

- 2013 – The 1994 Pentagon decision restricting women from combat positions in the military is overturned

- 2016 – Hillary Rodham Clinton wins the Democratic presidential nomination, becoming the first U.S. woman to lead the ticket of a major party[76]

Critiques of Movements

#FreetheNipple

“Is fighting for gender equality really as simple as removing your top?” – Alice Whelan[77]

Image of popular free the nipple poster found on Helloflo.com[78]

As with every topic duality will always be a factor. With this being said, there have been a few outliers critiquing the Women’s Rights Movement. One of them being the 2012 “Free the Nipple” movement, which gathered critiques from transgender women, who claimed the movement failed to acknowledge the fact that different body types may be seen differently, sexually as well as fetishly. Transgender women also criticized the #FreetheNipple movement for sololy advocating freedom for women’s bodies instead for all bodies.[79]

Women’s March on Washington

The Women’s March in Washington D.C in 2017 was also heavily criticized, largely due to the event’s name and racism.[80] The first and most obvious factor people criticized was the movement’s choice in name. Originally the movement’s organizators named the event “Million Women March,” which received backlash due to this name being taken from a prior black-led rally in Washington D.C. back in 1997.[81] The Million Women March was created as a response to the 1995’s Million Man March protesting discrimination solely against black men, excluding black women. After being reprimanded on this choice of name, the organizators of the Women’s March changed the name from Million Women March to “March on Washington.” This name change, however, did not satisfy the people who had their doubts with the first name choice due to the second name also having been used in the past for a black-led march in 1963. The overall critique in both of the name choices was that of the organizers using the work of African Americans and framing it as their own, discrediting the work and the ‘original’ issues of the black-led marches.

The second critique of the Women’s March was that of racism. The Black Lives Matter movement was compared to the Women’s March in terms of the movement’s course with the police and its counter movements.[82] The focus was set on how the Women’s March proceeded in a peaceful manner whereas the Black Lives Matter movement made a headlines within the media with a few disruptive demonstrations.The critique here is that these are two very different and uncomparable movements. The Women’s March was organized by white cis- gender women and was largely attended by white female individuals whereas the Black Lives Matter movement was created and attended mainly by black individuals.[83] The ultimate argument is that a movement or protest’ success cannot be measured at the hand of whether or not it proceeded in a peaceful manner, especially when police’s response to certain movements may vary. As Bustle author Mariella Mosthof states white, cis-women “are no more to credit for a peaceful, arrest-free march than peaceful black protesters are to blame for militarized police showing up to their events.”[84]

Women’s March in Washington D.C. captured by Yahoo![85]

“He For She” campaign

A further campaign which received criticisms in terms of advocating for women’s rights was that of Emma Watson’s “He For She” campaign. Similar to the 2017 Women’s March, the name of the campaign was heavily criticized. “He For She” was denounced as reinforcing gender binaries. By using the pronouns ‘he’ and ‘she,’ people who do not identify with these two genders are automatically excluded from this campaign. Suggestions to rename this campaign to “Stand With Women” have been made in the past with the reasoning of shifting the emphasis of the campaign’s name from standing up for women to standing alongside women in the fight for equality. Additionally, transgender people and people of color were excluded from this campaign, causing a flood of criticisms about the “He for She” campaign.

HeForShe logo by PwC[86]

Conclusion

Overall many strides have been made in the past towards gender equality, however society has only touched the surface and there are many more changes to be made. Diverse movements and campaigns advocating for Women’s Rights have evolved over the years and have led to movements such as #FreetheNipple, the “He For She” campaign, as well as the 2017 Women’s March in Washington D.C. With the use of social media platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, messages are spread and shared with people all around the world, impacting and raising awareness on multiple topics within the Women’s Rights Movement. It is important to note that although social media can play a crucial role in amplifying online movements, more action must be taken to visibly impact the offline decision-making processes. This chapter has focused on various social media platforms and the impact these platforms have had on the different movements advocating for Women’s Rights. With the implementation of social media platforms various movements were amplified allowing for fast information distribution as well as a spread of awareness. Without the implementation certain movements would not exist or have evolved as far as we see them today.

Author Biography – Meet the Authors

Sasha Fleischner | sashafleischner@berkeley.edu | www.linkedin.com/in/sasha-fleischner/

Sasha is a fourth-year UC Berkeley student who is currently pursuing a degree in Media Studies. To further strengthen her understanding in communications she enrolled in the Business AC course focusing on social media platforms’ impact on both online as well as offline social movements.

Megan Rodef | meganrodef@berkeley.edu | https://www.linkedin.com/in/megan-rodef

Megan Rodef is a fourth-year Media Studies major at UC Berkeley. She is graduating in Spring of 2018. After graduating she plans on pursuing an occupation in public relations or marketing. She is a huge women’s rights activist and is very dedicated to the movement.

Melinda An | melinda.an@berkeley.edu | https://www.linkedin.com/in/melindaan/

Melinda is a fourth-year Business Administration major at Cal. She hopes to find innovative solutions to global issues through her interest in technology, ethics, and human interactions. In her free time, she enjoys finding new music and reading personal development books.

[1]“Womens Rights.” HistoryNet, www.historynet.com/womens-rights.

[2]Eisenberg, Bonnie, and Mary Ruthsdotter. “Living the Legacy: The Women’s Rights Movement (1848-1998).” National Womens History Project, 1998, www.nwhp.org/resources/womens-rights-movement/history-of-the-womens-rights-movement/.

[3] Shaw, Alexis. “The History of the Women’s Rights Movement in the US.” AOL.com, Susan Milligan, 20 Jan. 2017, www.aol.com/article/news/2017/01/21/timeline-the-womens-rights-movement-in-the-us/21659519/.

[4] “History of the Women’s Rights Movement.” National Womens History Project, www.nwhp.org/resources/womens-rights-movement/history-of-the-womens-rights-movement/.

[5] Rampton, Martha. “Four Waves of Feminism.” Four Waves of Feminism, 25 Oct. 2015, www.pacificu.edu/about/media/four-waves-feminism.

[6] Ibid.

[7]Elissa. “What Does Feminism Mean in 2017? Why so Many Men & Women Hate It?” Iris Lillian, 17 July 2017, irislillian.com/what-does-feminism-mean-2017/.

[8]Rampton, Martha. “Four Waves of Feminism.” Four Waves of Feminism, 25 Oct. 2015, www.pacificu.edu/about/media/four-waves-feminism.

[9]Shaw, Alexis. “The History of the Women’s Rights Movement in the US.” AOL.com, Susan Milligan, 20 Jan. 2017, www.aol.com/article/news/2017/01/21/timeline-the-womens-rights-movement-in-the-us/21659519/.

[10] Nerren, Alexa. “Women’s Rights Analysis.” Create Infographics, Charts and Maps – Infogram, infogram.com/womens-rights-analysis-1gge9m8k8o4dmy6

[11] Shaw, Alexis. “The History of the Women’s Rights Movement in the US.” AOL.com, Susan Milligan, 20 Jan. 2017, www.aol.com/article/news/2017/01/21/timeline-the-womens-rights-movement-in-the-us/21659519/.

[12]https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=all&geo=US&q=feminism

[13]History.com Staff. “Women Who Fought for the Vote.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 2009, www.history.com/topics/womens-history/women-who-fought-for-the-vote.

[14]Fisher, Lauren Alexis. “25 Inspiring Women Who Shaped Feminism.” Harper’s BAZAAR, Harper’s BAZAAR, 6 Oct. 2017, www.harpersbazaar.com/culture/features/g4201/famous-feminists-throughout-history/?slide=1.

[15] Fisher, Lauren Alexis. “25 Inspiring Women Who Shaped Feminism.” Harper’s BAZAAR, Harper’s BAZAAR, 6 Oct. 2017, www.harpersbazaar.com/culture/features/g4201/famous-feminists-throughout-history/.

[16] Rosenberg, Sari. “August 26, 1970: Betty Friedan Led the Women’s Strike for Equality.”Lifetime, 26 Aug. 2017, www.mylifetime.com/blog/she-did-that/august-26-1970-betty-friedan-led-the-womens-strike-for-equality.

[17] Fisher, Lauren Alexis. “25 Inspiring Women Who Shaped Feminism.” Harper’s BAZAAR, Harper’s BAZAAR, 6 Oct. 2017, www.harpersbazaar.com/culture/features/g4201/famous-feminists-throughout-history/?slide=10.

[18] Fisher, Lauren Alexis. “25 Inspiring Women Who Shaped Feminism.” Harper’s BAZAAR, Harper’s BAZAAR, 6 Oct. 2017, www.harpersbazaar.com/culture/features/g4201/famous-feminists-throughout-history/?slide=15

[19] Fisher, Lauren Alexis. “25 Inspiring Women Who Shaped Feminism.” Harper’s BAZAAR, Harper’s BAZAAR, 6 Oct. 2017, www.harpersbazaar.com/culture/features/g4201/famous-feminists-throughout-history/?slide=16

[20] Fisher, Lauren Alexis. “25 Inspiring Women Who Shaped Feminism.” Harper’s BAZAAR, Harper’s BAZAAR, 6 Oct. 2017, www.harpersbazaar.com/culture/features/g4201/famous-feminists-throughout-history/?slide=24

[21]Fisher, Lauren Alexis. “25 Inspiring Women Who Shaped Feminism.” Harper’s BAZAAR, Harper’s BAZAAR, 6 Oct. 2017, www.harpersbazaar.com/culture/features/g4201/famous-feminists-throughout-history/?slide=25

[22]https://twitter.com/emmawatson/status/514168485107482624?lang=en

[23]https://twitter.com/ladygaga/status/919698717392887808?lang=en

[24]Timp, Steph. “Social Media and Feminism.” Linkedin, 12 June 2016, www.bing.com/cr?IG=5BB443C8788546F9933E8B55CA7488D0&CID=1193094AEA03601D2A5D0201EB0561D5&rd=1&h=kHmPiDO7EsY11igywCX7KTjeMMqtIbeddbctoKLmZDY&v=1&r=https%3a%2f%2fwww.linkedin.com%2fin%2fstephanietimp&p=DevEx,5082.1.

[25] Watson, Tom. “Networked Women as a Rising Political Force, Online and Off.” TechPresident, techpresident.com/news/23135/networked-women-rising-political-force-online-off/.

[26] Bennett , Jessica. “Ray Rice: Women Use Social Media to Talk Domestic Violence, Feminism.” Time, Time, 14 Sept. 2014, time.com/3319081/whyistayed-hashtag-feminism-activism/.

[27] Perrin, Andrew. “Social Media Usage: 2005-2015.” Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech, 8 Oct. 2015, www.pewinternet.org/2015/10/08/social-networking-usage-2005-2015/.

[28] Chittal, Nisha. “How Social Media Is Changing the Feminist Movement.” MSNBC, NBCUniversal News Group, 6 Apr. 2015, www.msnbc.com/msnbc/how-social-media-changing-the-feminist-movement.

[29] http://www.mtv.com/news/2169497/yes-all-women-one-year-later/Speller, Katherine. “Looking Back At The Success (And Failure) Of #YesAllWomen.” MTV News, 29 May 2015, www.mtv.com/news/2169497/yes-all-women-one-year-later/.

[30] Hoover, Kelly (May 24, 2014). “Press Release—05241402: Sheriff’s Office Releases Details of Shooting Rampage in Isla Vista”. Santa Barbara County Sheriff’s Office. Archived from the original on June 6, 2014. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

[31] Grinberg, Emanuella. “Why #YesAllWomen took off on Twitter”. CNN. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

[32] Bennett, Roxanna. “Yes, All Women.” Gender Focus Yes All Women Comments, 26 May 2014, www.gender-focus.com/2014/05/26/yes-all-women/.

[33] Hootsuite.com. “UN Women’s #HeForShe Solidarity Movement for Gender Equality.” UN Women’s #HeForShe Solidarity Movement for Gender Equality, 2015, socialbusiness.hootsuite.com/forrester-groundswell-awards-2015.html.

[34] “About HeForSheBlog”. 16 November 2014.

[35]Hootsuite.com. “UN Women’s #HeForShe Solidarity Movement for Gender Equality.” UN Women’s #HeForShe Solidarity Movement for Gender Equality, 2015, socialbusiness.hootsuite.com/forrester-groundswell-awards-2015.html.

[36] Heavey, Susan. “Time Magazine Names #MeToo ‘Silence Breakers’ as Person of the Year.”Reuters.com, Thomson Reuters, 6 Dec. 2017, www.reuters.com/article/us-time-person/time-magazine-names-metoo-silence-breakers-as-person-of-the-year-idUSKBN1E01O7.

[37] Stubbleine, Allison. “Lady Gaga, Sheryl Crow and More Tweet #MeToo To Raise Awareness for Sexual Assault.”Billboard, 16 Dec. 2017, www.billboard.com/articles/columns/pop/7998799/metoo-harrassment-lady-gaga-sheryl-crow-twitter-more.

[38] https://twitter.com/Alyssa_Milano/status/919665538393083904

[39] Esco, Lina. “’Free the Nipple’ Is Not About Seeing Breasts.” Time, Time, 11 Sept. 2015, time.com/collection-post/4029632/lina-esco-should-we-freethenipple/.

[40] Chemaly, Soraya. “Why Female Nudity Isn’t Obscene, But Is Threatening to a Sexist Status Quo.” The Huffington Post, TheHuffingtonPost.com, 22 Apr. 2014, www.huffingtonpost.com/soraya-chemaly/female-nudity-isnt-obscen_b_5186495.html.

[41] Zeilinger, Julie. “Here’s How Many Nipples #FreeTheNipple Has Liberated So Far.” Mic, Mic Network Inc., 25 Oct. 2015, mic.com/articles/124146/here-s-what-the-free-the-nipple-movement-has-really-accomplished#.GavDZMKke.

[42] Esco, Lina. “’Free the Nipple’ Is Not About Seeing Breasts.” Time, Time, 11 Sept. 2015,

[43] Dazed. “The Problems with #FreeTheNipple.” Dazed, 30 Mar. 2016, www.dazeddigital.com/artsandculture/article/30554/1/the-problems-with-freethenipple.

[44] Nateog. “Stand with Wendy: Texas Senator’s Abortion Bill Filibuster Captivates the Internet.”The Verge, The Verge, 26 June 2013, www.theverge.com/2013/6/26/4465316/texas-senator-abortion-filibuster-wendy-davis.

[45] Chittal, Nisha. “How Social Media Is Changing the Feminist Movement.” MSNBC, NBCUniversal News Group, 6 Apr. 2015, www.msnbc.com/msnbc/how-social-media-changing-the-feminist-movement.

[46] LaFrance, Adrienne. “The Weird Familiarity of 100-Year-Old Feminism Memes.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 26 Oct. 2016, www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2016/10/pepe-the-anti-suffrage-frog/505406/.

[47] QuoteDetails. “Quote from Mary Hirsch.” The Quotations Page, QuotationsPage.com and Michael Moncur. , n.d., www.quotationspage.com/quote/25912.html.

[48] Soykan, Hattie. “28 Memes You Should Send To Your Feminist Friend Right Now.”BuzzFeed, Buzzfeed, 7 Apr. 2017, www.buzzfeed.com/hattiesoykan/memes-you-should-send-to-your-feminist-friend-right-now?utm_term=.jh60BdmJ3#.yr4zJoZ4q.

[49] Weiss, Suzannah. “8 Twitter Hashtags Every Feminist Should Follow.” Bustle, Bustle, 4 Nov. 2016, www.bustle.com/articles/191626-8-twitter-hashtags-every-feminist-should-follow.

[50] Weiss, Suzannah. “8 Twitter Hashtags Every Feminist Should Follow.” Bustle, Bustle, 4 Nov. 2016, www.bustle.com/articles/191626-8-twitter-hashtags-every-feminist-should-follow.

[51] Hardy, Freya. img.huffingtonpost.com/asset/56f01bbe1e0000b300704d4c.png?cache=xzj7dykj1n&ops=1910_1000. 2 Apr 2015.

[52] WAVAW.ca. “What Is Rape Culture?” WAVAW.CA, 2014, www.wavaw.ca/what-is-rape-culture/.

[53] “Cultivatingculture.com.” Cultivatingculture.com, www.cultivatingculture.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/michael-courier-rape-culture.jpeg.

[54] Workneh, Lilly. “#YouOkSis: Online Movement Launches to Combat Street Harassment.”TheGrio, 2 Aug. 2014, thegrio.com/2014/08/02/youoksis-online-movement-launches-to-combat-street-harassment/.

[55] Ionenewsone.files.wordpress.com, ionenewsone.files.wordpress.com/2014/07/twitterchat_tiffany_france.jpg?quality=80&strip=all&w=650&h=450.

[56] Chittal, Nisha. “How Social Media Is Changing the Feminist Movement.” MSNBC, NBCUniversal News Group, 6 Apr. 2015, www.msnbc.com/msnbc/how-social-media-changing-the-feminist-movement.

[57] Bahadur, Nina. “Victoria’s Secret ‘Perfect Body’ Campaign Changes Slogan After Backlash.”The Huffington Post, TheHuffingtonPost.com, 6 Nov. 2014, www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/11/06/victorias-secret-perfect-body-campaign_n_6115728.html.

[58] Bell, Sarah (June 11, 2011). “Slutwalk London: ‘Yes means yes and no means no'”. BBC News.

[59] “Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence.” About Us: Million Mom March, Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence, 2016, www.bradycampaign.org/about-us-million-mom-march.

[60] James, George (October 31, 1999). “Politics and Government; Mothers Hope They’re One in a Million”. New York Times. Retrieved January 22, 2013.

[61] Schmidt, Kiersten, and Sarah Almukhtar. “Where Women’s Marches Are Happening Around the World.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 17 Jan. 2017, www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/01/17/us/womens-march.html.

[62] Przybyla, Heidi M., and Fredreka Schouten. “At 2.6 Million Strong, Women’s Marches Crush Expectations.” USA Today, Gannett Satellite Information Network, 22 Jan. 2017, www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2017/01/21/womens-march-aims-start-movement-trump-inauguration/96864158/.

[63] Belkin, Lisa. “’History!’: Journey to the March on Washington Feels like an End and a Beginning.” Yahoo! News, Yahoo!, 22 Jan. 2017, www.yahoo.com/news/history-journey-to-the-womens-march-on-washington-ends-in-triumph-024856955.html.

[64] Cauterucci, Christina. “The Women’s March on Washington Has Released an Unapologetically Progressive Platform.” Slate Magazine, 12 Jan. 2017, www.slate.com/blogs/xx_factor/2017/01/12/the_women_s_march_on_washington_has_released_its_platform_and_it_is_unapologetically.html.

[65] Keating, Fiona. “Pink ‘Pussyhats’ Will Be Making Statement at the Women’s March on Washington.” International Business Times UK, 18 Jan. 2017, www.ibtimes.co.uk/pink-pussyhats-will-be-making-statement-womens-march-washington-1601088.

[66] Womensmarch.com. “Speakers.” Women’s March, www.womensmarch.com/speakers/.

[67] Bates, Karen Grigsby. “Race And Feminism: Women’s March Recalls The Touchy History.”NPR, NPR, 21 Jan. 2017, www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2017/01/21/510859909/race-and-feminism-womens-march-recalls-the-touchy-history.

[68] “What Is CODEPINK.” CODEPINK, www.codepink.org/about.

[70] “What Is CODEPINK.” CODEPINK, www.codepink.org/about.

[71] “What Is CODEPINK.” CODEPINK, www.codepink.org/about.

[72] “What Is CODEPINK.” CODEPINK, www.codepink.org/about.

[73] “What Is CODEPINK.” CODEPINK, www.codepink.org/about.

[74] “What Is CODEPINK.” CODEPINK, www.codepink.org/about.

[75] “TakeAction.” CODEPINK, www.codepink.org/splash?splash=1.

[76] Milligan, Susan. “Stepping Through History.” U.S. News & World Report, U.S. News & World Report, 20 Jan. 2017, www.usnews.com/news/the-report/articles/2017-01-20/timeline-the-womens-rights-movement-in-the-us.

[77] Whelan, Alice. “Free the Nipple Is a Problematic Campaign.” Trinitynews, 14 Dec. 2016, trinitynews.ie/free-the-nipple-is-a-problematic-campaign, http://trinitynews.ie/free-the-nipple-is-a-problematic-campaign/

[78] Helloflo.com, helloflo.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/free-the-nipple.png

[79] Whelan, Alice. “Free the Nipple Is a Problematic Campaign.” Trinitynews, 14 Dec. 2016, trinitynews.ie/free-the-nipple-is-a-problematic-campaign, http://trinitynews.ie/free-the-nipple-is-a-problematic-campaign/

[80] Mosthof, Mariella. “If You’re Not Talking About The Criticism Surrounding The Women’s March, Then You’re Part Of The Problem.” Bustle, Bustle, 11 Sept. 2017, www.bustle.com/p/if-youre-not-talking-about-the-criticism-surrounding-the-womens-march-then-youre-part-of-the-problem-33491.

[81] Mosthof, Mariella. “If You’re Not Talking About The Criticism Surrounding The Women’s March, Then You’re Part Of The Problem.” Bustle, Bustle, 11 Sept. 2017, www.bustle.com/p/if-youre-not-talking-about-the-criticism-surrounding-the-womens-march-then-youre-part-of-the-problem-33491.

[82] Mosthof, Mariella. “If You’re Not Talking About The Criticism Surrounding The Women’s March, Then You’re Part Of The Problem.” Bustle, Bustle, 11 Sept. 2017, www.bustle.com/p/if-youre-not-talking-about-the-criticism-surrounding-the-womens-march-then-youre-part-of-the-problem-33491.

[83] Chittal, Nisha. “How Social Media Is Changing the Feminist Movement.” MSNBC, NBCUniversal News Group, 6 Apr. 2015, www.msnbc.com/msnbc/how-social-media-changing-the-feminist-movement.

[84] Mosthof, Mariella. “If You’re Not Talking About The Criticism Surrounding The Women’s March, Then You’re Part Of The Problem.” Bustle, Bustle, 11 Sept. 2017, www.bustle.com/p/if-youre-not-talking-about-the-criticism-surrounding-the-womens-march-then-youre-part-of-the-problem-33491.

[85] Mobili, Mobilus In. “Women’s March on Washington.” Flickr, Yahoo!, 29 Jan. 2017, www.flickr.com/photos/52257493@N00/32593123745.

[86] PricewaterhouseCoopers. “Making Great Strides in Support of the UN’s HeForShe Movement.” PwC, www.pwc.com/gx/en/about/stories-from-across-the-world/making-great-strides-in-support-of-the-un-heforshe-movement.html.