PAGE NAVIGATION

- Introduction

- Context

- Key Actors

- Social Media Presence

- Impact of Movement

- Critiques of Movement

- Conclusion

Introduction

#NoDAPL

#NoDAPL is a social media campaign for the fight against the planned construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline through the sacred Indian Reservation lands called Standing Rock Indian Reservation. The notable impact and success of the #NoDAPL Movement has modernized and changed the way social movements can use social media to their advantage, particularly with the Facebook check-in feature. The role social media has played in the preservation of the Standing Rock Indian Reservation is invaluable. Because of the widespread use of social media in the progress of the movement, it is now commonly referred to by the hashtag, #NoDAPL. The hashtag stands for the overall movement which first had a grassroots startup in 2016, then rapidly evolved across the globe and grew into many other associated hashtags with even more reach. This movement is unique in that the youth from the Standing Rock tribe were the original organizers of this social media movement. The goal of this movement is to communicate on behalf of the indigenous people of North Dakota for the preservation of the sacred land and water in the surrounding areas, both of which are threatened by the building of the pipeline.

Protesters holding up a sign “Defend the Sacred”[1]

Protesters holding up a sign “Defend the Sacred”[1]

Context

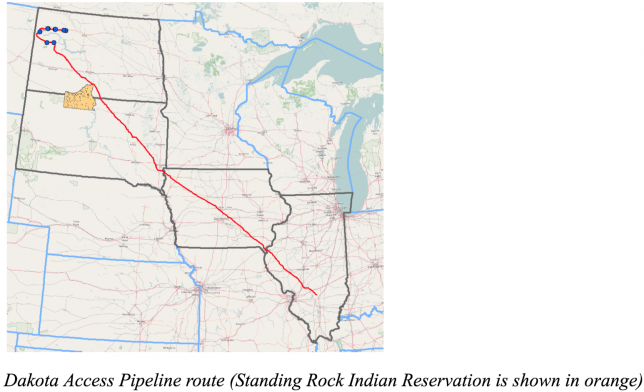

The Dakota Access Pipeline is a part of the Bakken pipeline project, which consists of a underground oil pipeline that stretches 1,172-mile-long (1,886 km) across the United States.[2] The layout of the pipeline runs from the Bakken oil fields in North Dakota to Southern Illinois, crossing beneath the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers and Lake Oahe, which is where the Standing Rock Indian Reservation lays. The Standing Rock tribe opposes the project because it threatens the sanctity of their land that has sacred burial grounds for their people and it also threatens their water quality. The project was proposed in the summer of 2014 with a $3.78 billion dollar budget plan. When Energy Transfer Partners announced the construct of an oil pipeline route stretching across cultural, spiritual, and environmental significant lands and waterways to the Standing Rock tribes as well as other communities along the river, the #NoDAPL movement began.[3]

The Standing Rock Indian Reservation was the original source and location of the protests. This area is occupied by various indigenous tribes and is the sixth-largest Native American reservation in land area in the United States. The Standing Rock Sioux Indian Reservation in North Dakota is where the people of Lakota and Dakota of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe live. The tribe has occupied areas throughout North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, Nebraska, Wyoming, Minnesota and Iowa.[4] The Dakota Access Pipeline was rerouted near the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation after it was settled that the old route near the capital was too damaging for the water.[5] However, the new route was heavily opposed by the tribes at Standing Rock because it threatened to damage both their water and sacred land, as it still passed through the Mississippi River. A camp, named Sacred Stone Camp, was created in response to this concern and served as “a center for cultural preservation and spiritual resistance to the Dakota Access Pipeline.”[6]

Dakota Access Pipeline route (Standing Rock Indian Reservation is shown in orange)[7]

Timeline:

June 2014

Announcement of Dakota Access Pipeline. On June 25, 2014, Energy Transfer Partners approved and announced the pipeline project.[21]

January 2016

Approval of Dakota Access. In January 2016, the North Dakota Public Service Commission approves the permit for he Dakota Access.[22]

March 2016

Beginning of online movement. In March, plans to reroute the Dakota Access Pipeline through sacred land led to the Standing Rock Youth to take action. This petition would eventually lead to the Standing Rock Youth’s #ReZpectOurWater campaign.

April 2016

Opposition by the Sacred Stone Camp. In April, a hearing for Native Americans on the pipeline was held by U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, in which there was near unanimous opposition to the project, according to reports of local media reports. Along with this, the Sacred Stone Camp was created close to where the intersection of the Missouri and Cannonball rivers.[23] The goal of this camp was for the construction pipelines to end and with this, protect the water.

June 2016

Fundraisers emerge. In June, Dakota Access Pipeline Resistance fundraisers pop up across U.S., such as “Benefit Show for Water Warriors” and GoFundMe Accounts.

September 2016

Protests went viral. In September, the tensions at the Standing Rock began to heighten. This was due to the North Dakota law enforcement pepper spraying water protectors as well as unleashing dogs upon them[24], which various individuals at Standing Rock recorded, uploading them to social media platforms in order to present to the rest of the world what was occuring at the camp. The aftermath of this tension led to over thirty people being sprayed by police with pepper spray. Additionally, a total of six individuals were attacked by the unleashed dogs.[25] On September 26th 2016, a meeting of 500 Native American leaders took place along with President Obama during his final White House Tribal Nations Conference. In this meeting, President Obama voice his opinion on the disputes around the pipeline, furthermore promising that he would ensure “every federal agency truly consults, listens, and works,” with American Indians until the Dakota Access Pipeline crisis is resolved.

October 2016

Protests and arrests, online and offline. In October 2016, Native American activists and allies started using various social media tactics, such as Facebook Live[26] to broadcast further standoffs that occured between protesters and police. Organized protests across various locations from Iowa to the Mississippi river led to hundred gathering for a communal goal to stop the construction. The protests that emerged led to several arrests occur. One of the most impactful protests occurred on Indigenous People’s day leading to 30 people being arrested at a prayerful demonstration including famous actress Shailene Woodley. [27] Later that month, the check-in feature on Facebook led to thousands of people starting to check in to the Standing Rock Reservation[28]. After rumors that Police were monitoring the social network to keep track of water protectors, he check-ins were an attempt to confuse police. However, local police denied these rumors, which meant the effort did not achieve what allies were hoping for.

November 2016

Executive Order for Expulsion of Protestors. On November 28th, an executive order for the expulsion of DAPL protesters “to safeguard against harsh winter conditions” was issued by the governor of North Dakota, Jack Dalrymple.[29]

January 2017

President Trump approves Construction. On January 24th, President Donald Trump approved the construction of the Pipeline. He signed a presidential memorandum which directed federal agencies, which included the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, to expedite reviews in order to start the construction of the pipeline.[30]

February 2017

Closing of protest sites. The protesters were forced to leave the camp in February 2017, thus, leading to the closure of the protest site. Most individuals left the site voluntarily, however, some individuals remained strong, leading to ten individuals being arrested. All in all, even with these few arrests, no major conflict occurred.

April 2017

Construction completed. By April 2017, the construction of the pipeline was completed.[31]

May 2017

First Oil Delivery. The first time oil was pumped through the pipeline occurred on the 14th of May, 2017.[32]

Controversy:

The construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline received backlash due to various reasons. Mainly, the Energy Transfer Partners failed to talk with tribes about how building the pipeline would affect the environment and their lands. This occurred despite the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), along with the U.S. Department of Interior (DOI) and the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, pressuring Energy Transfer Partners to do so.

Also, the importance of the land is strongly debated. The location where the pipeline route crosses the Missouri is part of a myth about how the tribe was born into the world after the great flood, creating the Mandan origin. The confluence of the Missouri and Cannonball rivers created the spherical Sacred Stones, which is why the colonizers termed the river ‘Cannonball’. However, these rivers were flooded and dredged in the 1950s, which led to the change of waterflow and thus leading to the inability of the spiritual Sacred Stones to be produced.[8] Additionally, there are concerns that the construction of the pipeline would impact historic burial grounds along the proposed construction site. Ultimately, the construction project poses various threats, ranging from human rights to environmental rights.

“Resistance” sign at the drilling site[9]

Key Actors

The Standing Rock Sioux Indian Reservation is home to the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. The tribe strongly objects the construction of the pipeline since the construction of the pipeline would take place less than one half of a mile away from their reservation. The tribe wants to maintain their independence to preserve their cultural resources and spiritual connection to the area.[10] The tribe also fought against DAPL in order to honor their ancestors because the pipeline would invade important religious sites for the tribe. Several tribes have passed resolutions in support of Standing Rock, including the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, Crow Creek Tribe, the Oglala Sioux Tribe, the Rosebud Sioux Tribe, and others.[11] These resolutions support the sovereignty of the tribes against government control and interference. Many people have flocked to the site of Sacred Stone Camp from around the world to show support for indigenous rights and their land rights.

Resistance by Native Americans who have joined the Standing Rock Sioux tribe members in their protest[12]

The campaign against the Dakota Access Pipeline was mainly initiated and spread by the indigenous youth. The teenagers at Standing Rock effectively used social media to share their protests and stories with the world. Specifically, many credit fourteen year old, Tokata Iron Eyes and her friends with starting the #NoDAPL movement.[13] One of Iron Eyes friends, Anna Lee Rain Yellowhammer, who is also a resident of Standing Rock and part of the Sioux tribe, created a petition on Change.org, called “Stop the Dakota Access Pipeline.”[14] These youth took a firm stance against the pipeline construction, using their voices to make their opposition to the pipeline loudly and proudly heard.

In response to the youth of the Sacred Stone Camp’s social media campaign, the International Indigenous Youth Council (IIYC) was formed. This council is comprised of youth from all nations, tribes, and races, who together fight to protect their collective land, water, and people.[15] This group came together nationally as well as internationally to follow the tradition of their elders and the American Indian Movement, forming a single solidarity movement to support one another. With this, the IIYC aimed to protect land, water, and treaty rights, and to empower the youth to become leaders in their respective indigenous communities through educational resources, civic engagement, and community meetings.

Perpetrators:

The construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline was initiated and completed with the help of numerous organizations and individuals. A network of international companies planned the route and construction process, the main one being Energy Transfer Partners, which owns 51 million dollars of the pipeline’s shares. Enbridge Energy Partners, Marathon Petroleum Company, and Phillips 66 also own substantial shares of the pipeline. The project was financed by numerous banks, such as SunTrust, Citibank, and Wells Fargo, due to the immense $3.8 billion dollar price tag. Many of these banks, especially Wells Fargo, received criticism for funding the controversial project.

The construction of the pipeline had initially been blocked by President Obama, however, under President Trump, construction of the pipeline was expedited.[16] Trump signed an executive memorandum directing the U.S. Army “to review and approve in an expedited manner” the pipeline, “to the extent permitted by law and as warranted.”[17] Trump also ordered an end to protracted environmental reviews by signing a directive, citing his belief that environmental regulations are destructive to businesses. This change in agenda reversed many of the impactful environmental policies, specifically regarding climate change, that were key under Obama’s presidency. Trump owns stock in Energy Transfer Partners, according to his most recent filing with the Federal Election Commission, which has led to some additional controversy.

Image shows water protectors standing in solidarity with the Standing Rock camp protests.[18]

Social Media Impact

Physical and digital protests against the pipeline project have gone viral, as thousands of social media users have used #NoDAPL in Facebook and Twitter posts to show their allegiance with the Standing Rock Tribe. #NoDAPL stands for ending the pipeline construction in addition to recognizing the independence and civil rights of indigenous communities. In a Facebook video that gained more than one million views overnight, Iron Eyes, the creator of the hashtag, said,”This entire movement was brought up by the youth… it just started so small…. and now, the easement for DAPL was denied.”[19]

International Indigenous Youth Council Instagram Post [20]

The #NoDAPL movement manifested and spread via social media platforms, such as Instagram, Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. Perhaps the most used feature was the Facebook Live video tool that allowed users across the globe to watch the violations against the indigenous people and land. This feature enabled people to unify without a physical presence. Shortly after the hashtag’s initial use, millions started tweeting with associated hashtags, like #StandWithStandingRock.

The NoDAPL Movement Check In:

On Twitter, the hashtag was even more popular. The protest received little coverage on national news in comparison to the social media buzz surrounding it. They also did not call themselves protesters; instead, they saw themselves as “protectors.”[33] This is because the tribes “set up makeshift camps in the pathway of development in an attempt to safeguard their drinking water as well as their burial and prayer sites…”[34]This situation changed when activists began to use Facebook’s check-in feature in an attempt to support the “protectors.” “Standing Rock Sioux Tribe spokeswoman Sue Evans said the Facebook check-ins didn’t come from the tribe, but “grew organically,” in part because of a mistrust of the sheriff’s office.”[35]Activists utilized Facebook’s check-in feature as a tool to spread awareness on the issue, creating world-wide check ins.[36] “While the tribe wasn’t behind the viral posting, Evans said members have been heartened by the outpouring of social media support. The hashtags #standwithstandingrock and #nodapl were trending for months before the check-ins began.”[37]

They started checking in because “the Morton County Sheriff’s Department has been using Facebook check-ins to find out who was at Standing Rock in order to target them in attempts to disrupt the prayer camps.”[38] Users would post on their Facebook page that they “checked in” to the Standing Rock Indian Reservation— even if they were not physically present there— in order to show solidarity and make their opposition against the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline publically heard. This tool was effective because it allowed the movement to grow nationally, as supporters from all parts of the country were able to show their support for the Standing Rock Tribe.

It also reveals the evolution of social media as a tool for protests and activism, and how the #NoDAPL movement redefined Facebook tools and digital protests. The check-in feature gained popularity because the police began tracking protesters who used this feature, so to protect them, thousands of other activists also checked in as an effort to confuse the police. Quicky after this, more than one million people checked in to the location.[39] “The number of check-ins at the Standing Rock reservation page went from 140,000 to more than 870,000 by Monday afternoon… Now, that number stands at more than 1.5 million,” the Guardian reported. “ Prior to these check-ins, the Morton County Sheriff’s Department used the Facebook feature of check-ins to identify the protester; however, the department denied the accusation of the usage of check-in data. Ultimately, the usage of the check in feature ultimately allowed for the movement to gain wide attention due to its presence on social media. The numbers showed that “as of Monday afternoon, the Facebook page for the Standing Rock Indian reservation had been “visited” more than 868,000 times and liked more than 310,000 times. A stream of five-star ratings—the page has more than 7,000 of them—came with messages of support, many of them copied from earlier post.” [40]

However, some say the check-ins were being monitored, although the Morton County Sheriff dismissed the accusation. Morton County Sheriff’s denial ignores the fact that technology companies often partner with police departments to track social media for information on upcoming protests. Many technology firms require that their “clients sign non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) before working with them.”[41] Some tech companies market themselves to police departments solely for this reason, like the social media monitoring firm Gefeedia. Thus, the public may never know if the Morton County Sheriff’s Department was telling the truth when they claimed not to monitor the #NoDAPL check ins, as they could have been outsourcing the information.[42]

Compared to prior online social movements, the Dakota Access Pipeline uniquely used various tactics on the Internet and social media to advance its goals. Additionally, previous movements have often relied on organizational structures, whereas the check-in movement behind #NoDAPL movement occurred sans the help of a specific organization or the Sacred Stone Camp.[43] The check-in feature was started by a few users on Facebook and quickly gained momentum as other users learned of what was happening and began showing their support.

A Facebook user checking in at Standing Rock Indian Reservation

In contrast, some users argued that the Facebook check- in feature did little to actually strengthen the movement. “While the protesters in North Dakota have said they appreciate the show of support on Facebook, there’s no evidence anyone is helping them by checking in on the social network.”[45] Sacred Stone Camp wrote a public relations response to the specific effect of the Facebook feature that reads as follows:

“The check in’s have created a huge influx of media attention that we appreciate. Our growing massive social media following plays a key role in this struggle. We have been ignored for the most part by mainstream media, yet we have hundreds of thousands of supporters from across the world. We appreciate a diversity of tactics and encourage people to come up with creative ways to act in solidarity, both online and as real physical allies.

We would like to see these thousands of people take physical action to demand that their banks divest, their police forces withdraw, and the Army Corps and Obama administration halt the construction of this pipeline. We would like CitiBank, Bank of Tokyo and Mizho Bank to cancel their pending $1.1 billion dollar loan to DAPL. We’d also like to see people connect with indigenous and environmental struggles in their own bioregion. We’d like you to investigate and organize around your personal relationship to fossil fuel consumption and colonization.”[46]

Along with the use of the check-in feature, Facebook pages were also created in alignment with the movement. These included “Standing Rock Sioux Tribe,” “Standing Rock Stories,” “Heart of Standing Rock,” and “Standing Rock Rising.” Each of these pages highlighted different aspects of the “No Dakota Access Pipeline” Movement, from presentations of water protector camps, to calls for prayers, to rallies for non-violent direct action. They included many personal posts by indigenous people, such as art and interviews, as well as memes.

Hashtags used:

While #NoDAPL was the most popular hashtags, a number of other hashtags emerged up on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram to protest the building of the pipeline. These hashtags include #ReZpectOurWater, a play on the word “reservations,” #StandWithStandingRock, and #WaterisLife, which was used to show that the availability of clean water is an issue that affects people in marginalized communities, like those who live on Indian reservations, disproportionately more. [47] The hashtags on Twitter also spread so widely that Twitter accounts with the theme and name of these hashtags popped up around the globe (such as usernames like “DreamcatcherNoDAPL,” “#NoDAPL #Rezpect,” and twitter user’s normal name with the #NoDAPL hashtag next to it).[48]

Reach:

Numerous celebrities, like Shailene Woodley, Bill McKibben, Leonardo DiCaprio and Ndaba Mandela, have taken active stances in support of the protests against the North Dakota Pipeline. They have helped raise awareness and public attention for the pipeline construction plans. Bernie Sanders, for example, used social media to tweet about the movement on October, 31, 2016, “There are many reasons the North Dakota Access Pipeline should be stopped.”

Presidential candidate Jill Stein also took to Twitter to raise awareness for the protests. An example of her tweet on October 28, 2016, calls out other political leaders, saying, “Your silence is terrifying @HillaryClinton and @realDonaldTrump. #noDAPL.” Stein was a very involved activist, as she visited the Standing Rock camp multiple times and was even nearly convicted for vandalizing Dakota Access corporation equipment.[49] With the help of the political and celebrity figures who effectively spread awareness regarding the environmental issues and human rights infringements at Standing Rock, the movement was able to start a petition against the Dakota Access construction that gained over 460,000 signatures.[50]

Bernie Sanders’ Twitter Post supporting the #NODAPL movement https://twitter.com/SenSanders[51]

Dr. Jill Stein Twitter Post addressing Presidential Candidates in support of the #NODAPL movement https://twitter.com/DrJillStein[52]

Individuals from all around the world who could not be physically present at the protest site used social media to show their support, tweeting and posting about the movement to raise awareness for the cause. Many individuals also attended the protest sites in person, including celebrities.

Divergent actress Shailene Woodley brought a lot of attention to the movement when she was arrested for protesting. She was was arrested and charged in October with criminal trespassing and engaging in a riot while protesting the controversial project at the Standing Rock reservation in North Dakota.[53] Woodley live-streamed her arrest at Standing Rock on Facebook Live.[54]

Shailene Woodley Twitter Post from Protest Site[55]

She stated shortly after her arrest: “I was arrested on Oct. 10, on Indigenous Peoples’ Day, a holiday where America is meant to celebrate the indigenous people of North America. I was in North Dakota, standing in solidarity, side-by-side with a group of over 200 water protectors, people who are fighting the Dakota Access Pipeline.”[56]

Meme Culture:

As the movement progressed, humorous memes that related to the #NoDAPL Movement action began emerging and spreading through Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. As serious as the concerns over the proposed pipeline were, users began using the situation to create memes and cartoons on social media to gain awareness.[57]

With the use of social media, the movement was able to attract a large following. However, it quickly became clear that activism in the digital space is not equivalent to activism in the physical space. There was a need to do something active to support the water protectors, which was accomplished through the sale of items supporting the movement on various sites, such as Amazon.[58] The Amazon wish list presented items for sale that the protesters who were fighting in horrendous conditions needed. It states“This list consist of the needs of members of the Standing Rock community who have been there for months and who plan to be there until DAPL is defeated. Many of the items are unique, but severely needed.”[59] In the social media age, there’s a difference between surface level support and physical help. Facebook posts and retweets were not going to keep the protestors alive in below-freezing temperatures or protected against rubber bullets.

Additionally, the Sacred Stone Camp created donation pages accepting financial donations that were then sent to various camps.[60] These pages included not only general donations for the movement, but also specific donation pages, such as #NODAPL Legal Defense, Standing Rock Media and Healer Council, and indigenous youth schools.[61]

Global Reach:

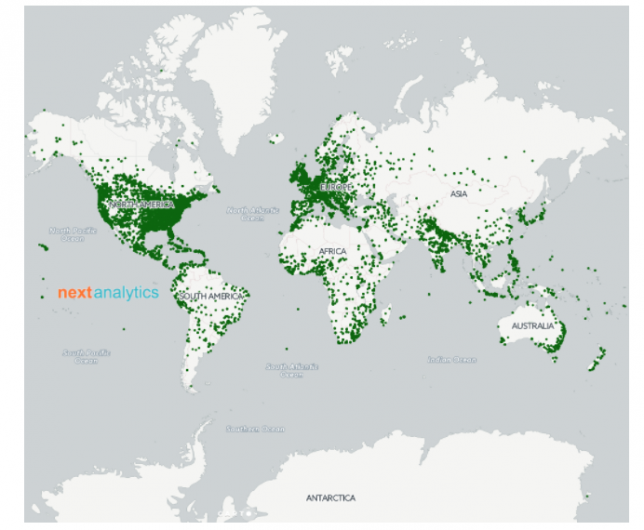

Rallies and protests across the U.S. expanded globally and encouraged people to stand in support against the Dakota Access Pipeline construction. The map of the world shown below illustrates the density of tweets from around the world, relating to the Dakota Access pipeline protest hashtags, like #NoDAPL, #standingrock, #standwithstandingrock, #waterislife. The impact the protests at Standing Rock have had across the globe is specifically concentrated in North America, Europe, Japan, and India.[62]

Usage of Hashtags to support the #NODAPL movement across the globe[63]

Impacts of Movement

The movement against the Dakota Access Pipeline was successful in terms of persistence. As early as April 2016, indigenous Lakota people established the Sacred Stone Camp with the mission to prevent pollution of the landa and waterways. Since then people have flocked to the camp to show support and unity against big businesses intervention in the reservation’s land. The protest was also successful in that it was able to unify people in the digital and physical spaces to protest the pipeline. People remained steadfast in their protests despite forceful action from the local and federal government. Protesters used their bodies as a physical blockades against federal authorities and the DAPL corporation to prevent construction of the pipeline. In regards to the planning stages, the movement remained fairly organized due to the commitment of the Sacred Stone residents. On the Internet, the Sacred Stone Camp website helped with structure of the movement by organizing a timeline of events. YouTube and Facebook live videos were also used to document and gain more awareness for the protests, thus fulfilling the provocation aspect of the movement. The Facebook Live sessions captured controversial police brutality and corporate violence. The videos have helped provide evidence against the Dakota Access corporation and the government. An example of this evidence out to action was when North Dakota Sheriff Gary Schwartzenberger was suspended after documentation was leaked of his inhuman violence against protesters.[64]

Loss of Movement:

The protests that occurred at the Standing Rock Reservation had many successes, in that they raised awareness for indigenous rights, as well as on environmental rights issues on water. However, in the end, the massive efforts did not turn out to be enough to win the long fought battle for the end of of the construction of the pipeline. The federal government under the Trump administration ultimately allowed for the construction of the pipeline, and now oil runs through the Dakota Access pipeline. The protests by thousands of indigenous natives and non-native demonstrators, as well as the online efforts that occurred throughout the span of a year were ultimately unsuccessful. [65]

Critiques of Movement

An international security firm known as TigerSwan targeted the movement opposed to the Dakota Access Pipeline with military-style counterterrorism measures, collaborating closely with police in at least five states, according to internal documents obtained by The Intercept.[66] TigerSwan is a firm that originated as a U.S. Military and State Department contractor helping to fight against the global war on terror. They worked with their client Energy Transfer Partners to stop the indigenous-led movement. TigerSwan described the movement as “an ideologically driven insurgency with a strong religious component” and compared the anti-pipeline water protectors to jihadist fighters.[67]

Tactics used against the movement:

The federal government implemented various tactics to lessen the impact of the protest. One way they did this was through the Federal Aviation Administration. This agency imposed a “temporary flight restriction,” also known as a no-fly zone that covered nearly 154 square miles of airspace above the pipeline resistance.[68] This zone was a response to the activities of indigenous drone pilots, whose aerial videos documenting the struggle at Standing Rock drew large social media followings. It was approved from October 25 to November 4 in 2016 and renewed twice to cover a smaller area, remaining in effect until December 13. After the flight ban, the media was not permitted to use aircraft to cover the events without undergoing a review process. Some have argued this tactic infringed on the protesters’ right to free speech because the government prevented access to the public protests and therefore limited the spread of knowledge to the rest of the globe. While this didn’t directly violate the First Amendment, it impeded access to the public protests, diminishing the impact, strength, and capacity of the movement.

Conclusion

Although the #NoDAPL movement was popularized and went viral on social media platforms, the outcome was not highly favorable. Steven Willard, a Standing Rock reservation inhabitant, said, “Since Columbus ‘discovered’ America, Native Americans have had to endure the worst of the worst. This is just going to be another object thrown at us that we will have to find a way to endure.”[69] The protest against the Dakota Access Pipeline project encompassed issues like violations of indigenous peoples rights that reached far deeper than simply environmental concerns. The conditions of the Standing Rock Reservation demonstrate how mistreated the native people are, subjected to the big business and government priorities. For example, about 40 percent of Standing Rock inhabitants live below the poverty line and suffer from high rates of unemployment, alcoholism and suicide. Additionally, the healthcare system is falling apart, and housing is so scarce that multiple families often cram into a single dwelling.[70] While the #NoDAPL movement brought attention about environmental hazards, it more importantly brought attention to the infringement of indigenous rights. Unfortunately, hope for the improvement of human rights was diminished with President Trump’s veto against stopping the construction. Today, the construction that the Standing Rock residents fought so hard for has been completed. However, the messages in support of indigenous rights and environmental protection that came from the movement continue to resonate across the globe.

The #NoDAPL protests reminded people that it is possible to unite and stand up against the government in a nonviolent way. The decision to continue the pipeline construction by the United States government highlights issues in our society regarding the mistreatment of indigenous people. The Dakota Access Pipeline controversy involves human rights violations and environmental concerns that will continue to surround contemporary political and civic discussion..

Team Member Bios:

My name is Victoria Rihm, and I am a Letters and Science Undergraduate Student at the University of California, Berkeley. I am currently majoring in Media Studies as well as earning my Minor in Global Studies. I am currently a Junior and am planning on graduating in Spring 2019.

My name is Cleary Chizmar, and I am a Business Administration and Art Practice double major at the University of California, Berkeley. I am a senior planning on graduating in the Fall with ambitions to work for an awesome, sustainable b-corporation doing creative strategy. I hope to combine my love for the outdoors with my artistic outlook.

My name is Brenda Garcia, and I am a third year undergraduate Political Science major at UC Berkeley. I am passionate about women in politics and have worked with former US Treasurer Rosie Rios through the IGNITE organization to put more women in positions of leadership. I am interested in social media movements as a way to help reach parity in politics.

[1] Clarkson, Frederick. “Defending the Sacred at Standing Rock.” Daily Kos, 29 Oct. 2016, https://www.dailykos.com/stories/2016/10/29/1588464/-Defending-the-Sacred-at-Standing-Rock. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

[2]Dalrymple, Amy. “Pipeline Route Plan First Called for Crossing North of Bismarck.” Bismarck Tribune, 18 Aug. 2016,

[3] “Dakota Access Pipeline Facts.” Dakota Access Pipeline Facts.

[4]“Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s Statement: Background on the Dakota Access Pipeline.” #NoDAPL Archive – Standing Rock Water Protectors , 15 Aug. 2016. Accessed 10 Dec. 2017.

[5] Baker, Peter, and Coral Davenport. “Trump Revives Keystone Pipeline Rejected by Obama.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 24 Jan. 2017. Web. 14 Dec. 2017.

[6] NAURECKAS, Jim. “Dakota Access Blackout Continues on ABC, NBC News.” FAIR: Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting, 22 Sept. 2016, fair.org/home/dakota-access-blackout-continues-on-abc-nbc-news/. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

[7] “Bakken Pipeline Map”. bakkenpipelinemap.com. n.d. Retrieved Accessed 5 Nov. 2017.

[8] “Proposed DAPL Route .” Camp of the Sacred Stones, sacredstonecamp.org/dakota-access-pipeline/. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

[9] LaDuke, Winona. “Winona LaDuke: The Dakota Access Pipeline … What Would Sitting Bull Do?” EcoWatch. EcoWatch, 30 Aug. 2016. Web. 11 Dec. 2017.

[10]“Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s Statement: Background on the Dakota Access Pipeline.” #NoDAPL Archive – Standing Rock Water Protectors , 15 Aug. 2016. Accessed 10 Dec. 2017.

[11] “Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s Statement: Background on the Dakota Access Pipeline.” #NoDAPL Archive – Standing Rock Water Protectors , 15 Aug. 2016. Accessed 10 Dec. 2017.

[12] LaDuke, Winona. “Winona LaDuke: The Dakota Access Pipeline … What Would Sitting Bull Do?” EcoWatch. EcoWatch, 30 Aug. 2016. Web. 11 Dec. 2017.

[13] Klein, Naomi. “The Lesson from Standing Rock: Organizing and Resistance Can Win.” The Nation, 9 Dec. 2016.

[14]“How young Native Americans used social media to build up the #NoDAPL movement.” Mashable , edited by Matt PETRONZIO, mashable.com/2016/12/07/standing-rock-nodapl-youth/#Zy.DoyxSDqqA. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

[15] “International Indigenous Youth Council (IIYC) .” #NoDAPL Archive – Standing Rock Water Protectors , www.nodaplarchive.com/international-indigenous-youth-council.html. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

[16] Baker, Peter, and Coral Davenport. “Trump Revives Keystone Pipeline Rejected by Obama.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 24 Jan. 2017. Web. 14 Dec. 2017.

[17] Ibid.

[18]Dolasia, Meera. “Why Native Americans And Environmentalists Are Up In Arms About The North Dakota Access Pipeline.” DOGOnews. N.p., 05 Dec. 2017. Web. 14 Dec. 2017. https://www.dogonews.com/2016/9/13/why-native-americans-and-environmentalists-are-up-in-arms-about-the-north-dakota-access-pipeline

[19] “How young Native Americans used social media to build up the #NoDAPL movement.” Mashable , edited by Matt PETRONZIO, mashable.com/2016/12/07/standing-rock-nodapl-youth/#Zy.DoyxSDqqA. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

[20] https://twitter.com/erynwisegamgee

[21]“Energy Transfer Announces Crude Oil Pipeline Project Connecting Bakken Supplies to Patoka, Illinois and to Gulf Coast Markets.” Business Wire, 25 June 2014, www.businesswire.com/news/home/20140625006184/en/Energy-Transfer-Announces-Crude-Oil-Pipeline-Project. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

[22] Javier, Carla. “A Timeline of the Year of Resistance at Standing Rock.” Splinter, Splinternews.com, 14 Dec. 2016.

[23] “We Will Stand.” Camp of the Sacred Stones, sacredstonecamp.org/about/. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

[24]“VIDEO: Dakota Access Pipeline Company Attacks Native American Protesters with Dogs and Pepper Spray.” Democracy Now!.

[26] Kozlowska, Hanna. “Dakota Pipeline Protesters Are Broadcasting Their Tense Standoff with the Police Using Facebook Live.” Quartz, Quartz, 29 Oct. 2016.

[27] “We Will Stand.” DAPL Timeline, sacredstonecamp.org/about/. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

[28] Lekach, Sasha. “Don’t Bother Checking into the Dakota Pipeline Protest to Confuse Police.” Mashable, Mashable, 31 Oct. 2016.

[29]“Next Test for Pipeline Protesters: The Brutal North Dakota Winter.” Chicagotribune.com, 2 Dec. 2016

[30] Dalrymple, Amy. “Trump Advances Dakota Access Pipeline, but Timeline Unclear as…” INFORUM, 24 Jan. 2017.

[31] Renshaw, Jarrett. “East Coast Refiner Shuns Bakken Delivery as Dakota Access Pipeline Starts.” Reuters, Thomson Reuters, 19 Apr. 2017.

[32]Cullen, Andrew. “East Coast refiner shuns Bakken delivery as Dakota Access Pipeline starts.” Reuters. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

[33] Frazier, Andrea. “What Does The Standing Rock Facebook Check-In Do? It’s A Way To Help & Protect Protesters.” Romper, 31 Oct. 2016. Accessed 11 Dec. 2017.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Hult, John. “Sorry, Your Facebook Check-ins at Dakota Pipeline Aren’t Confusing Police.” USA Today. Gannett Satellite Information Network, 01 Nov. 2016. Web. 14 Dec. 2017.

[36]Merelli, Annalisa. “Facebook Users All over the World Are Checking in at Standing Rock to Protest the Dakota Pipeline.” Quartz, Quartz, 31 Oct. 2016.

[37] Hult, John. “Sorry, Your Facebook Check-ins at Dakota Pipeline Aren’t Confusing Police.” USA Today. Gannett Satellite Information Network, 01 Nov. 2016. Web. 14 Dec. 2017.

[38] Rogers, Katie. “Why Your Facebook Friends Are Checking In to Standing Rock.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 31 Oct. 2016. Web. 14 Dec. 2017.

[39] Kennedy, Merrit. “More Than 1 Million ‘Check In’ On Facebook To Support The Standing Rock Sioux.” NPR, NPR, 1 Nov. 2016.

[40] Meyer, Robinson, and Kaveh Waddell. “Facebook Is Overwhelmed With Check-Ins to Standing Rock.” The Atlantic. Accessed 8 Oct. 2017.

[41] Landale, Jeff. “Standing Rock ‘check in’ marks turning point for activists.” The Christian Science Monitor. Accessed 12 Dec. 2017.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Meyer, Robinson, and Kaveh Waddell. “Facebook Is Overwhelmed With Check-Ins to Standing Rock.” The Atlantic. Accessed 8 Oct. 2017.

[44] Roman Podchernyaev. #NoDAPL 2016. Facebook, 1 Nov. 2016, https://www.facebook.com/roman.podchernyaev. Accessed 9 Dec. 2017.

[45] Kleinman, Alexis. “Checking in at Standing Rock on Facebook Is Cool – but Here’s How You Can Actually Help .”Mic, Mic Network Inc., 1 Nov. 2016.

[46] Kleinman, Alexis. “Checking in at Standing Rock on Facebook isn’t helpful — here’s what you can do instead.”Mic. Accessed 8 Oct. 2017.

[47] Fearless, J.H. “How the Nation’s Artists Are Standing with Standing Rock The #NoDAPLartmovement hashtag is bringing artists together in solidarity and resistance.” Creators. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

[48]“Stay informed about: #nodapl.” Twitter, https://twitter.com/hashtag/nodapl?f=users&vertical=default&src=rela. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

[49]Sammon, Alexander. “A History of Native Americans Protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline.” Mother Jones. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

[50] “Dakota Access: Stars From Hollywood to Washington Support Water Protectors.” Indian Country Media Network, 27 Aug. 2016.

[51] https://twitter.com/SenSanders

[52] https://twitter.com/DrJillStein

[53]FIsher, Luchina. “Shailene Woodley says she was strip searched after Dakota pipeline arrest.” ABC News. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

[54] Tesema, Martha. “Shailene Woodley Was Just Arrested While Protesting Dakota Access Pipeline.” Mashable, Mashable, 10 Oct. 2016.

[55] Shailene Woodley. “Shailene Woodley (@shailenewoodley).” Twitter. Twitter, 10 Sept. 2016. Web. 10 Dec. 2017.

[56] Woodley, Shailene. “Shailene Woodley: The Truth About My Arrest.” Time Magazine, time.com/4538557/shailene-woodley-arrest-pipeline/. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

[57]Carrejo, Cate. “#NoDAPL Memes & Tributes To Show Your Support For Standing Rock Protesters On Social Media.” Bustle , 25 Nov. 2016. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

[58] “Standing Rock Needs You.” Amazon, https://www.amazon.com/gp/registry/wishlist/18FR1AGDPWZLC/ref=cm_wl_sortbar_v_page_2?ie=UTF8&page=2. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

[59] Ibid,

[60] “Donate.” Camp of the Sacred Stones, sacredstonecamp.org/donate. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

[61] Ibid.

[62] “#NoDAPL Around the World.” Next Analytics, https://www.nextanalytics.com/nodapl-around-world/#iLightbox[gallery13480]/null. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

[63] Ibid.

[64]“Sheriff Gary Schwartzenberger removed from Office at Standing Rock DAPL Protest fro Alleged Bullying and Militant Police Actions.” Inquisitr, https://www.inquisitr.com/3745902/sheriff-gary-schwartzenberger-removed-from-office-at-standing-rock-dapl-protest-for-alleged-bullying-and-militant-police-actions/. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

[65]Mckenna, Phil. “Standing Rock’s Pipeline Fight Brought Hope, Then More Misery.” Inside Climate News, https://insideclimatenews.org/news/30032017/dakota-access-pipeline-standing-rock-protests-oil-obama-donald-trump. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

[66] Brown, Alleen, Will Parrish, and Alice Speri. “Leaked Documents Reveal Counterterrorism Tactics Used at Standing Rock to.” The Intercept. N.p., 27 May 2017. Web. 10 Dec. 2017.

[67] Ibid.

[68] Brown, Aleen. “Police Used Private Security Aircraft For Surveillance In Standing Rock No-Fly Zone.” The Intercept. Accessed 28 Nov. 2017.

[69] Brown, Alleen, Will Parrish, and Alice Speri. “Leaked Documents Reveal Counterterrorism Tactics Used at Standing Rock to.” The Intercept. N.p., 27 May 2017. Web. 10 Dec. 2017.

[70] McKenna, Phil. “Standing Rock’s Pipeline Fight Brought Hope, Then More Misery.” The Huffington Post. TheHuffingtonPost.com, 05 Apr. 2017. Web. 14 Dec. 2017.