Introduction

On January 21, 2017, two important historical events occurred: firstly, current U.S. president Donald Trump had his first full day in office as the leader of the free world; secondly, 4.1 million people in the United States marched for causes important to all those whose rights were threatened under the Trump administration.[1] This worldwide organized protest was the first of a series of protests within the movement known as the Women’s March. Women and men alike would march, year after year, to advocate for: the end of state-sanctioned violence, reproductive rights, LGBTQIA rights, workers’ rights, civil rights, disability rights, immigrant rights, environmental justice and many more. However, the movement didn’t begin on January 21; it was birthed over two months prior to Trump’s Inauguration date.

On November 8, 2016, another pair of simultaneous events took place: in D.C., the Trump administration celebrated its controversial victory in the 2016 Presidential Election. Meanwhile, in Hawaii, retired lawyer Teresa Shook created a Facebook event, stating that a pro-women march was needed in response to Trump’s victory. She shared it with just 40 friends, but she woke up to over 10,000 RSVPs and 10,000 more indicating interest. Many others, including prominent women’s rights activist Bob Bland, made Facebook events as well; these events eventually were consolidated, and half a million people showed up in Washington on January 21, 2017, to march for their rights. The Women’s March movement began with a single Facebook event that was initially shared to an audience of 40 and in a short period of time evolved into a historic day for women and other vulnerable communities around the world. Social media and its organizational capacities ultimately made the movement possible by bringing together minority groups around the world who felt vulnerable or threatened under Trump’s presidency; at the same time, social media catapulted this movement into the national spotlight before formal decision-making structures were established, resulting in the lack of many federal policies being achieved.

Soon after the creation of the Facebook event by Women’s March founder Teresa Shook, and four prominent women’s rights activists, Bob Bland, Tamika Mallory, Carmen Perez, and Linda Sarsour, came together to form the nonprofit Women’s March Inc.[2] These four would serve as organizers of the movement on the national level.

The march was originally named “Women’s March on Washington,” referencing Martin Luther King Jr.’s civil rights march of 1963.[3] The organizers even obtained the blessing of King’s daughter, Bernice, to use this name. In deciding the movement’s name, the organizers also considered “Million Pussy March,” which perpetuated a slur used by Trump. Shook created the event under the name “Million Woman March,” but the organizers decided against it because there was a 1997 protest by African American women that already used this name. The organizers eventually decided on “Women’s March on Washington” because of its similarity to the civil rights movement. The movement has been spread using the hashtag #WomensMarch.

After the first March in 2017, the movement continued to surge in popularity as the 2017 March joined people together in a great show of defiance against Trump. The 2018 March took place in January of 2018; it was very successful as many people showed up to rally behind women running for the 2018 midterm elections. In February 2018, the movement re-emerged under the national spotlight because the organizers were criticized for holding anti-Semitic viewpoints. Mallory attended a Nation of Islam event, where speaker Louis Farrakhan made many anti-Semitic comments. She later posted a photo of the two of them on her Instagram, lauding him and calling him the “GOAT” (Greatest of all Time). Her post did not condemn his anti-Semitic and anti-LBGTQIA comments, which began the controversy affecting the Women’s March.

Mallory and her co-organizers continued to deny the allegations that they endorse anti-Semitic beliefs; however, Mallory also refused to condemn Farrakhan’s statements. Shortly thereafter, it was revealed that Mallory and her co-organizer Perez had made anti-Semitic comments at Women’s March planning meetings. As a result, many former sponsors chose to disaffiliate themselves with the movement in March of 2019, resulting in a steep drop in attendance nationwide.[4]

Key Terms

State-sanctioned violence: violent acts perpetrated by the state or other government officials against its civilians

LGBTQIA: lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning, intersex, and asexual or allied

Reproductive freedom: access to safe, legal, affordable abortion and birth control for all people

Intersectional feminism: the idea that women’s rights are closely connected with racial justice for other minority groups

Geographic Mapping

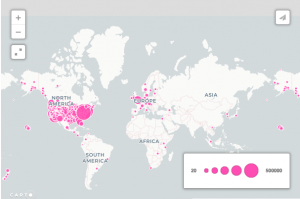

In 2017, the first year of the march, there were 4.1 million marchers across 654 cities in the United States.[5] The largest marches included 500,000 people in Washington D.C., 400,000 in New York City, and 100,000 in each Oakland, San Francisco, Seattle, Denver, Madison, and Portland.

Internationally, over 300,000 marchers showed up in 261 cities, including 100,000 marchers in London, 50,000 in Toronto, and 10,000 each in Melbourne and Vancouver.

The #WomensMarch movement is closely related to #NotMyPresident and #MeToo, both of which came about during Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign. #NotMyPresident is a movement which sprung up after Trump’s inauguration and has continued throughout his administration, in which people voice their dissent towards Trump’s presidency on social media and in person at riots.[8] Many people protesting for #NotMyPresident also showed up at the 2017 Women’s March to express their disapproval of Trump’s administration.

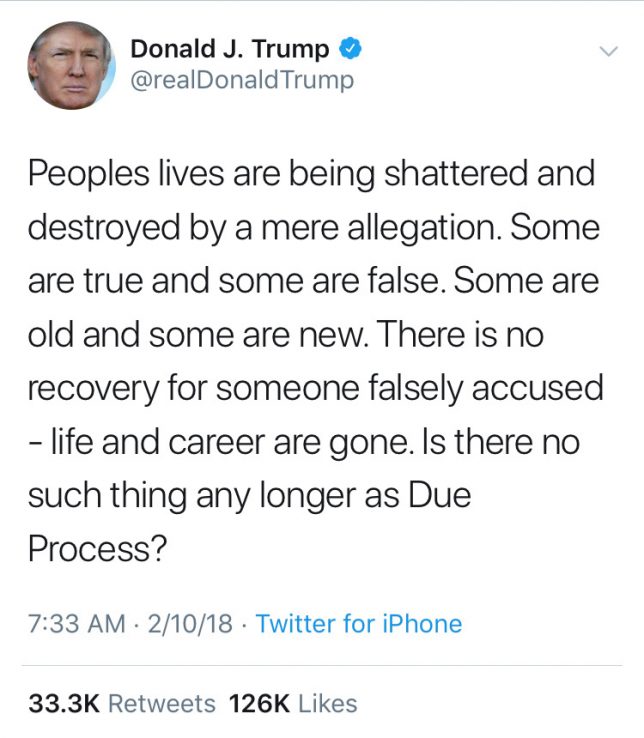

#MeToo is a movement against sexual harassment and violence that was founded in 2006; it became more prevalent in the United States during Trump’s campaign as his derogatory attitude toward women became more and more obvious.[10] Trump continued to defend the innocence of those whose actions had been called into question because of #MeToo, including his former staff secretary Rob Porter, who resigned when his two ex-wives accused him of domestic abuse.[11] Trump tweeted this the day after Porter’s resignation:

Trump’s tweet that was seen as a response to his former staff secretary resigning amidst allegations of domestic abuse.[12]The #WomensMarch movement deals with issues including gender justice, ending violence against women (#MeToo), police brutality and racial profiling (#BlackLivesMatter), gender and racial inequalities within criminal justice system, reproductive freedom, gender justice, LGBTQIA rights, equal pay, domestic worker rights, reproductive rights, and more. These issues were detailed in the Women’s Agenda that was released in December of 2018, which included 24 political issues that the organization intended to focus on over the next two years.[13]

The movement’s most recognizable symbol is the pink pussyhat: a bright pink, knit beanie that had ears like a cat.[14] The pussyhat’s significance references the infamous 2005 quote by Trump, in which he was caught saying, “Grab ‘em by the pussy.” The pussyhat symbol started from two women who wanted to find a way for Women’s March protesters to be united under a visual symbol during the first Women’s March in Washington D.C. They thus launched the Pussyhat Project, rapidly making and distributing matching pink hats.[15] However, the Pussyhat Project has garnered controversy, because “the pink pussyhat excludes communities and is offensive to transgender women and gender nonbinary people who don’t have typical female genitalia and to women of color because their genitals are more likely to be brown than pink.”[16]

Timeline

Prominent feminists convened and wrote a Declaration of Sentiments for women, which listed fundamental rights that women lacked.[18]

Seventy-two years later, the government finally ratifies the Nineteenth Amendment, allowing women to participate in democracy.[19]

Audio recorded of Donald Trump making objectifying comments toward a women in a TV trailer with Billy Bush on the set of “Days of Our Lives.”[21]

Donald Trump states that if Hillary Clinton were a man, “I don’t think she’d get 5 percent of the vote.” He adds: her only asset is “her woman card.”[22]

Donald Trump wins the GOP presidential nomination. He earned 1,237 delegates that got him the nomination.[23]

On the night of the 2016 election, retired lawyer Teresa Shook of Hawaii invited 40 of her friends on Facebook to her protest, “Women’s March.”[24]

The day after the event’s creation, Teresa Shook’s Facebook event had 10 thousand RSVPs and 10 thousand more indicating interest.[25]

Tamika D. Mallory, Bob Bland, Carmen Perez, and Linda Sarsour (from left to right) named as co-chairs of the movement.[26]

Over 4 million people show support of resistant to Trump administration. Sister marches are held in all 50 states and in over 30 countries globally.[27]

The Women’s March organization launched a campaign 10 actions to take in the first 100 days of Trump’s presidency.[28]

The Women’s March movement has its second annual March as the #MeToo movement urges people to join rallies.[29]

One of the Women’s March organizers, Tamika Mallory, attends a Nation of Islam event where speaker Louis Farrakhan says “powerful Jews are my enemy.”[30]

The audio recorded of Donald Trump and Billy Bush from 2005 was leaked by the Washington Post.

The Women’s Agenda is the first federal policy platform created by Woman’s March Inc. It includes 24 federal policies that the organization advocates for.[31]

Due to the anti-Semitism controversy, many sponsors such as the NAACPY, GLAAD, and the Human Rights Campaign withdrew their support.[32]

Key Actors

The movement’s inciting Facebook event, created on the night of the Trump’s election, was made by Hawaii resident and retired lawyer Teresa Shook. Shook is regarded as the founder of the Women’s March. The current leaders of the Women’s March include co-presidents and board members Tamika Mallory and Bob Bland, who work alongside co-board members Linda Sarsour and Carmen Perez.[33] These co-chairs were named in November of 2016, as they were already at the forefront of the women’s rights movement.

Mallory’s activism has roots in her family, as her parents were founding members of the National Action Network (NAN), a leading civil rights organization. Mallory served as NAN’s youngest Executive Director. She eventually went on to work closely with the Obama Administration as an advocate for civil rights issues, including women’s rights, healthcare, gun violence, and police misconduct.[34] Bland is the CEO and founder of Manufacture New York, an organization focused on transforming the apparel production process by creating sustainable and ethical supply chains. She is an advocate for domestic manufacturing.[35] Perez served as the Executive Director of the nonprofit The Gathering for Justice, fighting for various civil rights issues including mass incarceration and gender equality. She is also is the co-founder of Justice League NYC and of Justice League CA, which are state-based task forces for juvenile and criminal justice reform advocacy.[36] Lastly, Sarsour is a Palestinian-Muslim-American civil rights activist. She served as the former Executive Director of the Arab American Association of New York and, she also co-founded the first Muslim online organizing platform, MPower Change.[37]

The movement began in direct opposition to Trump’s election, and it drew national attention quickly with the help of social media. Celebrity endorsers include those who have advocated for the movement on various platforms and those who have actually attended Marches in various locations. Influential individuals such as Bernie Sanders, Hillary Clinton, Katy Perry, Lena Dunham, and Zendaya all supported the movement on Twitter. Viola Davis, Adele, Cameron Diaz, Jennifer Lawrence (pictured below), Natalie Portman, Chloe Grace Moretz, Ashton Kutcher, Mila Kunis, Padma Lakshmi, Drew Barrymore, Sarah Hyland, Olivia Munn, Scarlett Johansson, and Alyssa Milano have attended Marches in different locations.[38] Madonna, in particular, played a big part in the 2017 March as a performer. Before her performance at the March in D.C., Madonna stated, “The revolution starts here, it is the beginning of much-needed change, [but] change that will require sacrifice […] change will require many of us to make different choices in our lives. But this is the hallmark of revolution. So my question to you today is, are you ready?” She followed this crowd-arousing statement with her 1988 hit song “Express Yourself.”[39] Another influential individual within the Women’s March movement is Hillary Clinton. As the candidate opposing Trump in the 2016 presidential election, Clinton stands for the opposite of what Trump stands for. She is known for attending the Women’s March yearly, advocating for women’s rights all around the world, and sharing her thoughts on her official Twitter page.

The supporters of the Women’s March movement are extremely diverse, drawing together people from all races, genders, socio-economic backgrounds, and sexual orientations.[41] This movement aims to be inclusive and accept support from women and men as well as anyone who opposes President Trump’s degrading attitude toward women and other communities that are threatened under the Trump administration.

The #WomensMarch movement, in particular, is distinct from other movements in its annual and organized marches. Many other movements have protests sporadically or in response to catalyzing events; however, the #WomensMarch movement has an organized march once every year, composed of regional marches occurring simultaneously. In comparison to other movements related to women’s rights, #WomensMarch has a distinctively stronger on-the-ground, offline presence, as it centers around a physical demonstration of dissent toward and Trump administration and support for The Women’s Agenda. The whole movement is centered around an in-person representation of people’s feelings of discontentment, whereas other movements focus more on primarily sharing experiences on social media to dispel pluralistic ignorance, as opposed to in-person, physical demonstrations of dissent.

The movement has also brought together various organizations around the nation to be allied and united together under a single cause. Some of the 2019 Women’s March partners involve ACLU, Planned Parenthood, American Federation of Teachers, Sierra Club, Muslim Women’s Alliance, National Federation of Federal Employees, Disability Action for America, Youth Caucus of America, YWCA, American Medical Women’s Association, and more.[42] The organizations support the Agenda that the Women’s Organization published in December of 2018; they bring together people of various backgrounds to support a single movement. The involvement of the organizations listed above is important not only because of the support they offer the Women’s March, but also the environment they create that allows people from all backgrounds to feel included in the movement. These organizations help advertise the Women’s March and spread the word as well. But since the anti-Semitism controversy surrounding the March’s organizers, several prominent organizations, including the Democratic National Committee, Southern Poverty Law Center, Human Rights Campaign, and more have disaffiliated themselves with the 2019 Women’s March.[43] Compared to the list of the 550 sponsors that supported the 2018 March, less than half returned for the 2019 March.

Social Media Presence

The Women’s March movement has an impactful presence on social media, with the widest following coming from Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.[44] Social media allows the movement’s events to be streamlined, making it easier for individuals to join in.

The movement initially started with a Facebook event by Teresa Shook, who initially invited around 40 of her friends to the protest but ended up with over 10,000 followers overnight. Facebook’s organizational capacities have been utilized in this movement, as each regional march has its own Facebook event page with details as to when and where the march is taking place.

The event then transferred to Twitter with the hashtag #WomensMarch and received 11.5 million tweets in one day, almost as much as tweets about the actual inauguration of Donald Trump.[46] Organizers of the marches use Twitter to publicize the events, spreading awareness through the hashtag. Also on Twitter, people share memes and other content related to the Women’s March.

Instagram, although on a smaller and less interactive scale, was still successful in bringing influencers into the conversation regarding the movement.[47] A social media post about the Women’s March has garnered anywhere from a few hundred to even millions of likes. Instagram was often the go-to platform for Women’s March attendees to share photos of them at the marches.

Influential Posts

Memes have recently risen in popularity not only as a way to spread humor through images, but also to spread “social commentary” that depicts certain problems that are going on around the world.[53] Memes about Women’s March came in the form of internet images as well as signs during protests about Trump’s presidency and discrimination against women. Most of these memes contain a humorous twist on the derogatory comments by Trump, and they focus on causes such as the wage gap, female empower, and gender equality.

Social media started the movement through a Facebook event that went viral overnight. Without it, the movement would most likely not have taken place at all. Much of the popularity was also gained by the spread through social media platforms such as Twitter and Instagram, as well as online news platforms such as The Washington Post and The New York Times.

After the initial Facebook post went viral, Women’s March organizers focused on organizing the growth of the movement. They created the official Women’s March accounts on social media platforms such as Twitter (which has over 20,000 tweets), Facebook, Instagram, and their own website. Thus, a great deal of thought was put into planning the growth of the movement; in-person events revolve around a certain date that is predetermined and advertised ahead of time, which is crucial to the success and turnout of the protests.

However, much of the growth in the magnitude of the movement happened organically. While planned growth was a clear driver, with an established Women’s March Inc. led by four co-organizers, the movement also grew organically on social media. Teresa Shook’s original Facebook post garnered a huge overnight audience through organic growth, as it captured the attention of the right crowd of people. The Women’s March movement began in 2017 where technology and social media were so widespread, allowing for online media to be spread in a matter of seconds. 1.8 million Instagram posts and millions more on Twitter organically promoted the cause of women’s rights without the intervention of the organizers. Most politicians and celebrities joined on their own, all without paid marketing incentives from the Women’s March Inc.

The offline nature of the movement sets it apart from other movements born on social media. Although social media played a large part in organizing the event in the first place, most of the presence of the Women’s March movement happened outside of social media, in the streets of participating cities or regions. More than 4.2 million people attended the Marches in the first year of the movement’s launch, in 600 cities around the United States. Some say that the movement may have been one of the largest in the United States history judging by the magnitude of presence during these demonstrations.[56]

In terms of social media presence, the movement has utilized the most commonly-used social networks: Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. The movement began with a Facebook post that became viral overnight with 10,000 people signing up within one day.[57] Twitter became the biggest platform later on; used by politicians, celebrities, and organizers to provide general announcements and also to show support for the movement. Instagram also housed some of the most popular celebrity posts, often including pictures of people physically supporting the movement by marching in-person (such as the one by Adele).

Analog Antecedents

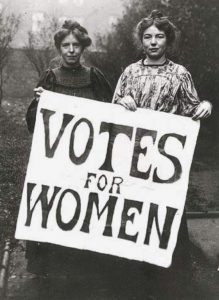

Though this movement was founded in 2016 at Trump’s inauguration, it has roots in the feminist movement in the United States that has pervaded throughout history. Feminism in the US started as early as the 19th century when women called for greater freedom for themselves as well as for the end of slavery. At the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848, leading women’s rights advocates such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott joined together, working to craft the Declaration of Sentiments that outlined several fundamental human rights that women deserved. At last, in 1920, women were granted the right to vote with the passage of the 19th Amendment.[58] Since then, women have fought for various causes related to their equality in society: fair treatment in the workplace, reproductive rights, equal pay, and more.

More recently, the feminist movement continued in 2006 with the creation of the #MeToo movement. The #MeToo movement was founded in in 2006 by an African-American woman named Tarana Burke, who sought to help and support survivors of sexual violence, particularly African Americans, find the path to recovery.[59] Over a decade later, on October 15, 2017, in the midst of an onslaught of news about Trump’s disturbing treatment toward women, actress Alyssa Milano tweeted the following tweet:

This tweet started a nationwide conversation that dispelled the pluralistic ignorance that sexual assault survivors once felt, empowering women to support each other through their shared experiences.[61]

Throughout Trump’s 2016 campaign trail, he continuously made comments that attacked women. Each of these attacks toward women and other marginalized communities made headlines, yet these moments of controversy did not prevent him from winning the Republican nominee and then become president-elect. During the campaign, Trump’s comments towards women furthered the objectification of women. His comments ranged from attacking women’s appearances to questioning their credibility as professionals. Trump consistently used women’s appearances to discredit them as full individuals. His comments about Hillary Clinton’s bathroom break during a 2015 debate as “too disgusting,”[62] coupled with his frequent comments about women’s weight, infuriated many women around the country. About a month before the 2016 election, the Washington Post published a report detailing Trump’s vulgar comments about women while filming a segment for “Access Hollywood” in 2005, inciting outrage from all sides of the political spectrum.[63] His comments were excused by some as locker room talk, while others felt deeply disgusted and attacked. Democrat nominee, Hillary Clinton, responded to the tape and tweeted:

Trump excused this behavior as mere locker room banter and suggested former president Bill Clinton has said much worse on the golf course.[65]

For many, it seemed as if Trump was given nothing but a slap on the wrist for his derogatory comments. Many strongly believed that if he talked about women this way, there was no way he could become the 45th president of the United States. All of his rhetoric toward women has created a strong opposition headed up by women While there was no official movement that preceded the Women’s March movement, the attacks made toward women globally by Trump created a strong sense of community among many women of all backgrounds to spark the creation of the Women’s March movement. This movement began as a response to Trump’s attacks against all different women, and it has now started to expand its advocacy work for immigrants, religious minorities, indigenous rights, LBGTQIA rights, and climate change.

Impact of Movement

The movement has yet to accomplish any federal policy changes because of its rapid organic growth caused by social media. Social media enabled the movement and the 2017 March to gain instant attraction and support. Since the movement quickly went viral through Shook’s Facebook event in November of 2016, the goals of the movement were just recently announced in December of 2018 before the third annual Women’s March. In December 2018, the Women’s March organization published the Women’s Agenda on their website. This was the movement’s first formal action into the realm of federal policy. The Women’s Agenda includes 24 policies related to immigrant rights, reproductive rights, and environmental justice. The Women’s Agenda will be the movement’s policy guide for the next two years.

While the movement has not achieved any policies as of today, the movement can be credited to expanding women’s and other marginalized communities’ roles in United States politics. According to Rutgers University, there were over 602 women likely to run for Congress or statewide office in 2018.[66] Additionally, there were 441,808 women who contributed at least $200 to federal political campaigns in the first half of 2017 according to a Center for Responsive Politics analysis.[67] The movement also accomplished a great deal in rallying many different people together to march in solidarity, sending a strong message to those in power.

Additionally, the Women’s March movement had a profound cultural impact on minority groups, bringing them into the conversation on gender equality. The movement began with the perfect Overton Window, as the movement exploded organically and drew 20,000 people on Facebook overnight. By reaching the intended audience overnight, the movement was able to draw together many different people in a short span of time.

Critiques of Movement

Although the Women’s March movement has been embraced by millions of individuals since its creation, there have been critiques of it by liberal activists, politically conservative groups, as well as original supporters with the start of its controversy around anti-Semitism.

In the first annual Women’s March in 2017, there was an overwhelming majority of white participants.[68] Some argued that if women of color did a march like this, they would be confronted by cops. Blogger Luvvie Ajayi states that “in a world that doesn’t protect women much, when it chooses to, it is white women it protects.”[69] Ajayi’s words are echoed by many other individuals critiquing the white privilege the Women’s March may have showcased.

Women of color who shared views Ajayi’s views are not the only critics of the first annual Women’s March. When the New Wave Feminists, a pro-life group, announced that they would be attending the first annual Women’s March movement in 2017, controversy sparked. Some individuals had doubts as to whether a group that aligns itself as pro-choice has a place in a march that aims to fight for all women.[70] Many New Wave Feminists and other female-lead pro-life groups argued that their reason for attendance was similar to their fellow peers, to oppose Donald Trump’s comments and conduct towards women.[71]

Shortly after the 2018 Women’s March, there erupt a strong feeling of opposition to the Women’s March when the anti-Semitism controversy started in February 2018. In February of 2018, Women’s March chair member Tamika D. Mallory attended a Nation of Islam event. During this event, Louis Farrakhan stated “powerful Jews are my enemy” and made anti-Semitic and anti-LBGTQIA remarks throughout his speech.[72] Mallory posted on her social media about her attendance to this Nation of Islam event, and followers around the nation were outraged at her support of Farrakhan. Fellow co-organizer Linda Sarsour swiftly rushed to defend Mallory.[73] It took the Women’s March organization over a week to respond to the outrage surrounding Mallory’s support of him.[74]

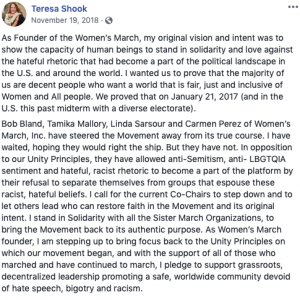

The Women’s March anti-Semitism controversy continued when Alyssa Milano stated that she would not speak at any Women’s March events if co-organizers Linda Sarsour and Mallory remain in charge. The Women’s March organization released a statement disavowing the language used by Louis Farrakhan, but the organization continued to support Sarsour and Mallory. Much of the public believes that the Women’s March organization has not addressed the anti-Semitism allegations adequately, as many of the movement’s original supporters started to withdraw right before the third annual Women’s March in 2019.[75] Even the founder of the march, Teresa Shook, called for all the organizers to resign. While the co-chairs who have been asked to step down, original supporters such as the NAACP, Democratic National Committee have withdrawn their support from the Women’s March leading to its third annual march to have its lowest attendance.[76] It is unclear how the Women’s March and organization will continue in the coming years as the controversy has not yet resolved itself fully.

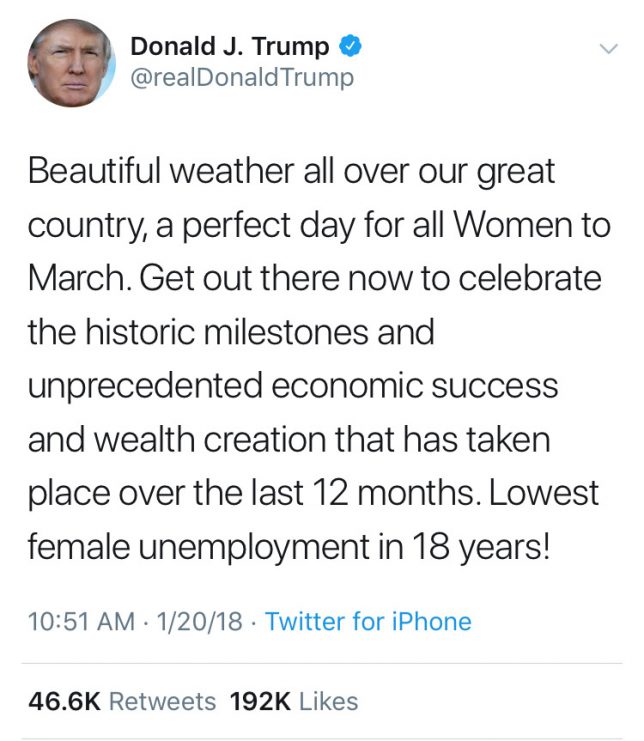

While there has been clear critiques of the movement from original supporters, liberal activists, and some more conservative groups, conservative media appears to ignore the subject of the Women’s March. President Trump did not even acknowledge the fact that the first Women’s March was in opposition of him; he reframed the march to represent a celebration of historic milestones and economic success of women.

Another seemingly quiet critique of the movement is its lack of policy achievements. Although we commend the Women’s March organization for publishing the Women’s Agenda in December 2018, we believe it should have been done sooner to establish clear goals and provide a structure within the movement. With a lack of a clear and strong comeback by the Women’s March organization in response to the anti-Semitism controversy, it is unclear if the Women’s Agenda will be able to command the authority and respect needed to create change. The movement may experience a downward spiral in attendance and reputation.

Conclusion

The movement has not yet ended, as it is an annual recurring march that will take place again next January and in smaller marches throughout the year. It is difficult to say whether or not this movement has been a success, as the Women’s Agenda was only released just over a year ago. However, in comparison to previous years, the 2019 March was more of a failure in terms of attendance, support from organizations, and the organization’s overall reputation. Because of the controversy surrounding the organizers’ anti-Semitic views, the movement as a whole suffered, seeing many people abstain from marching and many organizations abstain from sponsoring the March.

Nevertheless, releasing The Women’s Agenda can be considered a recent success; it brings hope for the future and a clearer metric of what success will look like. Furthermore, the March has been successful over the years in rallying women and men alike in a physical way, creating on-the-ground momentum to express disagreement with the Trump administration. The movement introduced women as the primary leaders of the Trump opposition, and it allowed for the huge group of female candidates (117) who ran for election and won in the 2018 midterm election.[77] It has diversified the entire Women’s Rights movement, intentionally making sure to include all people of color and LBGTQIA in the conversation about women’s rights going forward. The movement also introduced the idea of intersectional feminism, that women’s rights are closely connected with racial justice for other minority groups, making it an established tenet of left-wing politics.[78] All in all, the #WomensMarch movement has expanded the Overton Window of which parties are included in the women’s rights movement, including more minorities in the conversation about gender equality.

Author Biographies

Hannah is a fourth-year UC Berkeley student who is currently pursuing a degree in Ethnic Studies and a minor in Education. She is passionate about social justice and interested in business. She enrolled in the Social Media and Social Movements course offered through the Haas School of business to explore how to unite her two passions professionally.

Ariel is a third-year Business Administration major at UC Berkeley. She is interested in the intersection between technology, business, and social media. In the realm of business, she hopes to work for socially-conscious companies aiming to do more than generate revenue.

Angela is a third-year Economics major that is interested in pursuing a career in marketing, social media, and related fields. She believes the Social Media and Social Movements course would help her understand more about the role of contemporary media in facilitating causes and how it can apply to our everyday lives.

Maddie is a fourth-year Media Studies major at UC Berkeley. She is passionate about the marketing industry within the beauty, fashion, and entertainment fields. She is very interested in this class in the aspect of learning exactly how influential social media is in our current lives when it comes to the topic of politics.

Works Cited

[1] “Women’s March.” HISTORY. N. p., 2019. Web. 9 Apr. 2019.

[2] “Who Owns The Women’s March?.” The Daily Beast. N. p., 2019. Web. 20 Apr. 2019.

[3] Agrawal, Nina et al. “How The Women’S March Came Into Being.” latimes.com. N. p., 2019. Web. 9 Apr. 2019.

[4] “Anti-Semitism Concerns Leave The Future Of The Women’S March In Doubt.” Vox. N. p., 2019. Web. 22 Apr. 2019.

[5] “Here’s A Map Of Every Women’s March Across The Planet – Technical.Ly Brooklyn.” Technical.ly Brooklyn. N. p., 2017. Web. 9 Apr. 2019.

[6] Haltiwanger, John. “4 Amazing Statistics About The Women’s March That Will Drive Trump Crazy.” Elite Daily. N. p., 2017. Web. 9 Apr. 2019.

[7] “Here’s A Map Of Every Women’s March Across The Planet – Technical.Ly Brooklyn.” Technical.ly Brooklyn. N. p., 2017. Web. 9 Apr. 2019.

[8] Times, The. “Not My President, Not Now, Not Ever.” Nytimes.com. N. p., 2017. Web. 9 Apr. 2019.

[9] I.pinimg.com. N. p., 2019. Web. 30 Apr. 2019.

[10] “About – Me Too Movement.” Me Too Movement. N. p., 2019. Web. 9 Apr. 2019.

[11] Ducharme, Jamie. “Trump Just Went After the #MeToo Movement.” Time, Time, 10 Feb. 2018, time.com/5143101/donald-trump-tweet-allegations/.

[12] Trump, Donald (realDonaldTrump). “Peoples lives are being shattered and destroyed by a mere allegation. Some are true and some are false. Some are old and some are new. There is no recovery for someone falsely accused – life and career are gone. Is there no such thing any longer as Due Process?” 10 Feb 2018, 7:33 a.m. Tweet.

[13] “Womens Agenda – Womens March Network.” Womens March Network. N. p., 2019. Web. 9 Apr. 2019.

[14] “Pink Hats Of Protest: Why Women Are Ditching Symbol Of A Mov….” Duluthnewstribune.com. N. p., 2018. Web. 9 Apr. 2019.

[15] Shamus, K. (2018). Pink hats of protest: Why women are ditching symbol of a movement. [online] Freep.com.

[16] “Pink Hats Of Protest: Why Women Are Ditching Symbol Of A Mov….” Duluthnewstribune.com. N. p., 2018. Web. 9 Apr. 2019.

[17] “Pussyhats at Women’s March | Women’s March.” Know Your Meme, 22 Feb. 2018, knowyourmeme.com/photos/1333817-womens-march.

[18] “Feminism In America From 1792 Through The Millennium.” ThoughtCo. N. p., 2019. Web. 23 Apr. 2019.

[19] Ibid.

[20] “Feminism Isn’t Just A Modern Movement—It Dates To Antiquity.” HISTORY. N. p., 2019. Web. 23 Apr. 2019.

[21] “Transcript: Donald Trump’S Taped Comments About Women.” Nytimes.com. N. p., 2019. Web. 9 Apr. 2019.

[22] Bahadur, Nina. “22 Sexist Things President Donald Trump Has Said About Women.” SELF. N. p., 2019. Web. 9 Apr. 2019.

[23] It’S Official: Trump Wins GOP Presidential Nomination.” NBC News. N. p., 2016. Web. 9 Apr. 2019.

[24] Carson, Erin. “How Facebook, Twitter Jumpstarted the Women’s March.” CNET, CNET, 20 Apr. 2017.

[25] Ibid.

[26] “The Women’s March On Washington: How It Came To Be And What You Need To Know.” ELLE. N. p., 2017. Web. 9 Apr. 2019,

[27] “Women’s March.” HISTORY. N. p., 2019. Web. 9 Apr. 2019

[28] Novick, Ilana. “After The March: 10 Actions To Take In Trump’s First 100 Days.” Alternet.org. N. p., 2017. Web. 9 Apr. 2019.

[29] King, Laura, Andrea Castillo, and Nina Agrawal. “At Women’s Marches Nationwide, Setting Sights On The Ballot Box And Hailing #Metoo.” latimes.com. N. p., 2019. Web. 9 Apr. 2019.

[30] “A Timeline Of The Women’s March Anti-Semitism Controversies – Jewish Telegraphic Agency.” Jewish Telegraphic Agency. N. p., 2019. Web. 9 Apr. 2019.

[31] “Womens Agenda – Womens March Network.” Womens March Network. N. p., 2019. Web. 9 Apr. 2019.

[32] “Women’s March & 2019 Sponsors — Event Loses Top Sponsors | National Review.” Nationalreview.com. N. p., 2019. Web. 9 Apr. 2019.

[33] Scozzaro, Carrie. “Women’s March Founder Teresa Shook Shares Her Unlikely Path to Activism as She Visits Spokane.” Inlander, Inlander, 24 Mar. 2019.

[34] “Tamika D. Mallory.” Women’s March. N. p., 2019. Web. 22 Apr. 2019.

[35] “Bob Bland.” Women’s March. N. p., 2019. Web. 22 Apr. 2019.

[36] “Carmen Perez.” Women’s March. N. p., 2019. Web. 22 Apr. 2019.

[37] “Linda Sarsour.” Women’s March. N. p., 2019. Web. 22 Apr. 2019.

[38] Donahue, Rosemary. “18 Celebrities Who Came to the 2018 Women’s March.” Allure, Allure, 21 Jan. 2018.

[39] Przybyla, Heidi M., and Fredreka Schouten. “At 2.6 Million Strong, Women’s Marches Crush Expectations.” USA Today, Gannett Satellite Information Network, 22 Jan. 2017.

[40] Nast, Condé. “18 Celebrities Who Came To The 2018 Women’s March.” Allure. N. p., 2018. Web. 9 Apr. 2019.

[41] Turner, Karen, et al. “Vox First Person: The Vast Diversity of the Women’s March on Washington, in Words and Photos.” Vox, Vox, 21 Jan. 2017.

[42] Womens March Network, womensmarch.org/.

[43] Thelilynews. “Women’s March Local Chapters Are Distancing Themselves from the National Organization – and Fighting for Its Name – The Lily.” Https://Www.thelily.com, The Lily, 15 Jan. 2019.

[44] Carson, Erin. “How Facebook, Twitter Jumpstarted the Women’s March.” CNET, CNET, 20 Apr. 2017, www.cnet.com/news/facebook-twitter-instagram-womens-march/.

[45] “Women’s March on Washington” First Women’s March Facebook event. Facebook. 21 January 2017. https://www.facebook.com/events/independence-ave-third-st-sw/womens-march-on-washington/2169332969958991/ Accessed 1 May 2019 post was viewed.

[46] Cohen, David, and David Cohen. “Twitter: 12 Million Inauguration Tweets Friday, 11.5 Million Women’S March Tweets Saturday.” Adweek.com. N. p., 2019. Web. 9 Apr. 2019.

[47] “Https://Ew.Com/.” EW.com. N. p., 2019. Web. 9 Apr. 2019.

[48] Trump, Donald (realDonaldTrump). “Beautiful weather all over our great country, a perfect day for all Women to March. Get out there now to celebrate the historic milestones and unprecedented economic success and wealth creation that has taken place over the last 12 months. Lowest female unemployment in 18 years!” 20 Jan 2018, 10:51 a.m. Tweet.

[49] Clinton, Hillary (HillaryClinton). “This is horrific. We cannot allow this man to become president.” 7 Oct 2018, 1:55 p.m. Tweet.

[50] Women’s March (womensmarch). “BREAKING: The #WomensAgenda is here! Women’s March convened a policy table of 50+ women to craft the first intersectional feminist federal policy platform, and a unified declaration of what the women’s movement wants to see in 2019 and beyond.” 18 Jan 2019, 6:27 a.m. Tweet.

[51] Shook, Teresa (TeresaShookOfficial). “As Founder of the Women’s March…” https://www.facebook.com/TeresaShookOfficial/posts/as-founder-of-the-womens-march-my-original-vision-and-intent-was-to-show-the-cap/2368957223146495/ 19 November 2018. Facebook update.

[52] Women’s March (womensmarch). “Anti-Semitism, misogyny, homophobia, transphobia, racism and white supremacy are and always will be indefensible.” 6 March 2018, 8:13 a.m. Tweet.

[53] Commons.pacificu.edu. N. p., 2019. Web. 9 Apr. 2019.

[54] FeministNews (feministnews.us). “Today was truly historic.” https://www.facebook.com/feministnews.us/posts/397790260568198/ 21 January 2017. Facebook update.

[55] “The 40 Funniest Signs Protesting Trump and the GOP”. The Political Punchline. 20 Sep. 2018.

[56] “The Women’s Marches May Have Been The Largest Demonstration In US History.” Vox. N. p., 2017. Web. 9 Apr. 2019.

[57] Stein, Perry. “The Woman Who Started the Women’s March with a Facebook Post Reflects: ‘It Was Mind-Boggling’.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 31 Jan. 2017.

[58] “Feminism Isn’t Just A Modern Movement—It Dates To Antiquity.” HISTORY. N. p., 2019. Web. 23 Apr. 2019.

[59] “About – Me Too Movement.” Me Too Movement. N. p., 2019. Web. 23 Apr. 2019.

[60] Milano, Alyssa (alyssa_milano). “If you’ve been sexually harassed or assaulted write ‘me too’ as a reply to this tweet.” 15 October 2017, 1:21 p.m. Tweet.

[61] “A Year Ago, Alyssa Milano Started A Conversation About #Metoo. These Women Replied..” NBC News. N. p., 2018. Web. 23 Apr. 2019.

[62] “‘Horseface,’ ‘Lowlife,’ ‘Fat, Ugly’: How The President Demeans Women.” Nytimes.com. N. p., 2019. Web. 9 Apr. 2019.

[63] Fahrenthold, David A. “Trump Recorded Having Extremely Lewd Conversation about Women in 2005.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 8 Oct. 2016.

[64] Clinton, Hillary (HillaryClinton). “This is horrific. We cannot allow this man to become president.” 7 Oct 2018, 1:55 p.m. Tweet.

[65] “‘This Is Horrific’: Hillary Clinton Campaign Responds To Trump’s Lewd 2005 Comments About Women.” Business Insider. N. p., 2019. Web. 9 Apr. 2019.

[66] Dejean, Ashley. “The Women’S March Never Ended. These Stats Prove It..” Mother Jones. N. p., 2019. Web. 23 Apr. 2019.

[67] Ibid.

[68] Ramanathan, Lavanya. “Was the Women’s March Just Another Display of White Privilege? Some Think so.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 24 Jan. 2017.

[69] Ramanathan, Lavanya. “Was the Women’s March Just Another Display of White Privilege? Some Think so.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 24 Jan. 2017.

[70] Green, Emma. “These Pro-Lifers Are Headed To The Women’s March On Washington .” The Atlantic. N. p., 2017. Web. 9 Apr. 2019.

[71] Ibid.

[72] “A Timeline Of The Women’s March Anti-Semitism Controversies – Jewish Telegraphic Agency.” Jewish Telegraphic Agency. N. p., 2019. Web. 9 Apr. 2019.

[73] “Alyssa Milano Refuses To Speak At Women’s March Events Unless Co-Chairs Step Down.” The Independent. N. p., 2018. Web. 23 Apr. 2019.

[74] Ibid.

[75] Milman, Oliver. “Thousands Join Women’s March Across US As Controversy Dampens Turnout.” the Guardian. N. p., 2019. Web. 9 Apr. 2019.

[76] “Women’s March & 2019 Sponsors — Event Loses Top Sponsors | National Review.” Nationalreview.com. N. p., 2019. Web. 9 Apr. 2019.

[77] “A Record 117 Women Won Office, Reshaping America’S Leadership.” Nytimes.com. N. p., 2019. Web. 22 Apr. 2019.

[78] “The Women’S March Changed The American Left. Now Anti-Semitism Allegations Threaten The Group’S Future..” Vox. N. p., 2018. Web. 22 Apr. 2019.